India’s Cinematic Trident

Evgeniy Pakhomov, Bollywood, Tollywood and Kollywood

If 90% of the information about the world around us that reaches our brain is visual, cinematography should be given credit as one of the most important factors for a country’s ‘soft power.’ No one would dispute that premise in India. While its domestic film industry continues to take its lead from Hollywood, it does know a thing or two about making movies, and exporting them at a profit, in its own unique way

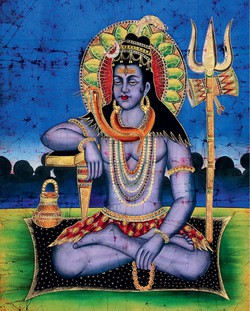

The history of Indian cinematography began in Bombay 100 years ago. It was back in 1913 that one of the industry’s founding fathers – Dadasaheb Phalke – made his debut feature film, Raja Harishchandra. To be fair, India had seen other movies before, usually with a static camera used to film theatrical plays. In contrast, Raja was a genuine feature film, with a storyline based on the ancient Indian epics the Ramayana and the Mahabharata. Phalke, inspired by Western cinematography, used camera techniques previously unseen in India. The movie blazed a trail for the future Indian film industry with its South Asian exotic charm, rajas, temples and legends captured on film using European and American cinematographic techniques. In the 1940s the Western press came up with an unflattering definition of the Indian film studios as a ‘Hollywood for the poor.’ The industry, based around Bombay (now Mumbai), came to be known as Bollywood (to draw an analogy with the ‘dream factory’ at the other end of the world).

For many Asian countries Indian movies turned out to be closer than those produced in Hollywood. Surely the culture and traditions also played a role. As a rule, Bollywood celebrates family values and principles that are more in line with tradition. It places characters in situations and social conditions that one can relate to

That was back in the 1940s. Today India would hardly qualify as poor, and the film industry in ‘the world’s largest democracy’ has long become a global leader. During Bollywood’s Golden Age in the 1950s, Indian movies made it to cinema screens across the world. At first these films, full of dancing, singing, and the inevitable happy ending, conquered India’s neighboring regions – Southeast Asia and the Arab countries. They then proceeded to penetrate the Iron Curtain and win over people’s hearts in the USSR, before finally making their way to the West.

The country’s film industry today has left the rest of the world far behind in terms of the number of movies released (around 1,000 per year in different languages spoken in India). Indian films are shown in nearly 100 countries – and not just in areas with large local Indian communities. And Bollywood has long since ceased to be the country’s only cinematographic centre – indeed, the number of different ‘-woods’ is mind boggling. There is Mollywood, making films in the Malayalam language, Ollywood, using the Oriya language, and Gollywood in the state of Gujarat.

However, the country’s largest and best-known centers remain Bollywood, Tollywood – with films in the Telugu language of Andhra-Pradesh (not to be confused with Bengali cinema, also sometimes referred to as Tollywood) – and Kollywood (Tamil cinema based in Chennai).

A trifurcated drive

Shashi Tharoor – a well-known Indian politician and writer – is positive that India’s drive to become a world leader should be rooted not only in the country’s economic or military prowess, but also its soft power, which includes its cultural influence and ability to project an image far beyond the boundaries of Hindustan. Tharoor believes that for India this soft power rests on three pillars: cinema, classical culture (dancing, music and so on), and cuisine.

One can only agree. After all, chicken curry has already conquered the Western world, and continues to find a way into the hearts of foreigners through their stomachs. Indian music is not far behind – we all recall how classical Indian sitars were favored by The Beatles, The Rolling Stones and Shocking Blue, among other bands. And many Western movie stars have dabbled in various forms of Indian dancing.

However, it is India’s film industry that is ranked as its most prominent soft power factor, and rightfully so – after all, cinema can serve to promote images, music, dancing and even cooking. Back in 2007 the prime minister, Manmohan Singh, stated that India’s national cinema could influence the world by telling the story of India’s growing role.

“No matter where I go – the Middle East or Africa – everywhere people talk about the Indian cinema,” he stated with satisfaction.

The Indian film industry is often accused of plagiarism and of ostensibly copying Western films, storylines, music and images. And that may, to an extent, be true. Bollywood is quick to borrow various stories and styles; for instance, the legendary Raj Kapoor was often reproached for imitating Charlie Chaplin. But Kapoor was just the tip of the iceberg – even the famous Disco Dancer, so popular among schoolgirls in the former USSR, was clearly inspired by the American-made Saturday Night Fever, and the songs featured in it were plainly based on Western disco hits popular at the time. And Russian audiences have only to watch the popular 2013 Bollywood film I Love New Year to see that the tradition of borrowing storylines is very much alive today in the Indian film industry: they will easily recognize the Soviet blockbuster The Irony of Fate, or Enjoy Your Bath!

And yet, is it true that Raj Kapoor was just a copy of Charlie? Not really. His character is a simple-minded attractive Indian man who maybe bears some resemblance to Chaplin. But he is first and foremost an Indian. Many of the heroes of Indian cinema – Dilip Kumar, Mithun Chakraborty, Dharmendra, Amitabh Bachchan, Salman Khan – while obviously influenced by a whole host of Hollywood superstars, from John Wayne and Paul Newman to Sylvester Stallone, still remain close to their audience, despite their occasional Stetson hats.

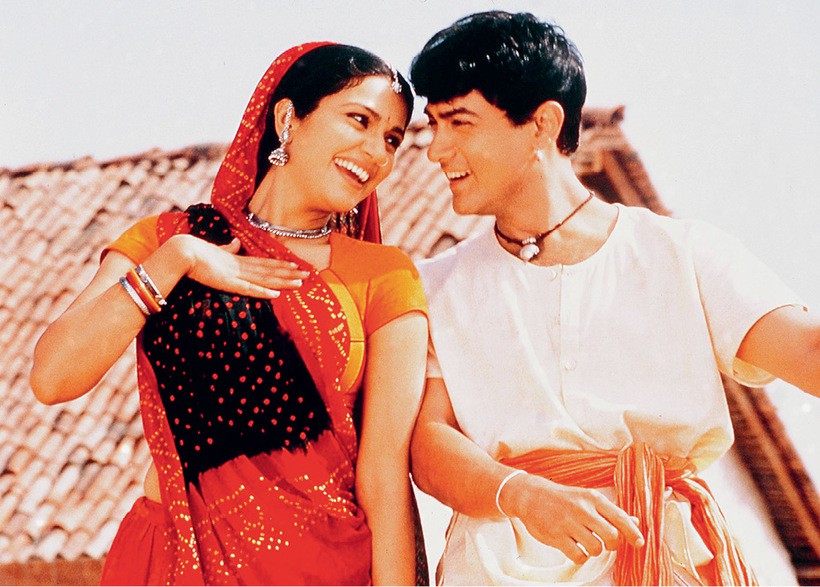

“The successes achieved by Bollywood and other Indian studios in Asia were predicated largely on the fact that for many neighboring countries these movies turned out to be closer than those produced in Hollywood. Surely the culture and traditions also played a role. For instance, in Western films a couple of teenagers in love would always run away from their parents to the other end of the world, while their Indian counterparts inevitably had to ask for the parents’ blessing. As a rule, Bollywood celebrates family values and principles that are more in line with tradition. It places characters in situations and social conditions that one can relate to,” Arjun Shrey, an Indian journalist who writes about cinema, told me.

Another factor contributing to the success of Indian films is that most of them feature singing and dancing, and have a happy ending. The connection with traditional Indian theater is clearly there: In the end, good always triumphs over evil, the village Cinderella becomes a princess, and the poor boy turns out to be a crown prince. It is not by accident that Boris Ivanov – a well-known Russian orientalist who lectures at Moscow State University – jokingly refers to Bollywood as opium for the people: The poor from rural areas and big cities alike are drawn to the silver screen to escape from their day-to-day problems. Naturally, India has its own social and art-house cinema; however, the vast majority of Indian films have nothing to do with real life. Bollywood and its sister studios definitely qualify as ‘dream factories,’ but with an oriental flavor, and certainly without any place for the poor Asian farmer.

“Our audiences prefer escapist movies. There has to be music, dancing, singing … It appeals more to our audience than any movie we could make about social problems,” Randhir Kapoor explained to me. Kapoor is the eldest son of Raj Kapoor and an actor, director and producer in his own right.

It certainly appears that Indians (or even Asians generally) are not the only audience to find such films appealing. Indian actors and directors were always exceedingly popular in the former Soviet Union. However, in today’s Russia this love affair with Bollywood seems to have run its course and Indian film studios are gaining a firmer foothold in Western markets. Indian cinema is changing, and while it still retains its colorful traits, it has become more appealing to audiences in Europe and the United States.

Many names from the new Bollywood generation are well known in the West, and Indian films have been receiving Oscar nominations since the late 1980s. In 1989, there was Salam Bombay! directed by Mira Nair, and in 2002 Ashutosh Gowariker’s Lagaan. (The first Indian movie to receive a nomination was a drama called Mother India, made back in 1958.) In 2001, Mira Nair’s Monsoon Wedding won the Golden Lion award in Venice. The famous director Baz Luhrmann has said that his musical comedy Moulin Rouge! – nominated for an Oscar in 2001 – was inspired by Bollywood films and their music and singing.

Widescreen diplomacy

The famous Indian film producer Kunal Kohli once told me that in his opinion Indian films were often on a par with those made by Western studios, but that the problem of management still remained: “Hollywood is very proactive and even aggressive in promoting its movies. We haven’t learned to do that yet,” he says. According to Kohli, Bollywood is ready to learn but it will take some time. Once this obstacle is out of the way the popularity of Indian films is likely to grow at a much higher pace.

All of this is ever more important for India. In recent years the country has come to view its film industry not just as a tool to support its economic and political ambitions, but also as a weapon against extremism.

The mass media in India often raise the following question: If the popularity that The Beatles and The Rolling Stones enjoyed among young people in socialist countries helped to overthrow communist regimes, can Bollywood play a similar role in the fight against religious – and primarily Islamic – fundamentalism?

Shikha Dalmia – a political analyst at think tank the Reason Foundation – believes that Western pop culture cannot offer an adequate response to fundamentalism due to a significant cultural divide. He has argued on reason.com that while young people in Pakistan or Saudi Arabia are certainly familiar with MTV music videos, Hollywood movies and Western music in general, Western culture does not enjoy a great deal of influence.

For radicals, these entertaining and light pictures are dangerous, with

their ‘sinful’ singing and dancing. In April 2007, Islamists from the

notorious Red Mosque in Islamabad organized a ceremony of videodisc

burning. They piled videodiscs and cassettes together to make a gigantic

bonfire that was set ablaze by the imam of the mosque, who claimed in

my presence the films were

For radicals, these entertaining and light pictures are dangerous, with

their ‘sinful’ singing and dancing. In April 2007, Islamists from the

notorious Red Mosque in Islamabad organized a ceremony of videodisc

burning. They piled videodiscs and cassettes together to make a gigantic

bonfire that was set ablaze by the imam of the mosque, who claimed in

my presence the films were

“sinful and lewd”

Bollywood is clearly a different story. Today the Middle East has become one of the main markets for the Indian film industry. Dubai, for instance, often plays host to Indian film festivals and premieres. Even though Pakistan introduced a ban on Indian cinema screenings following the Indo-Pakistani war of 1965, video stores have remained full of Bollywood movies. Pakistani audiences watch all of the latest Indian blockbusters and know all the Bollywood celebrities. And many Muslims star in Indian films, portraying the image of a modern man, a successful movie character who lives in peace with the tenets of his religion but whose mind has not been ‘polluted’ by the radicals. These films often feature a lot of music, including Sufi songs.

For radicals, these entertaining and light pictures are dangerous, with their ‘sinful’ singing and dancing. The Taliban in Afghanistan and Pakistan have been adamant about banning all films and television in the territories under their control.

In April 2007, I witnessed a ceremony of videodisc burning organized by Islamists from the notorious Red Mosque in Islamabad. Several months later the mosque, which by that time had become the headquarters for radicals who had declared a holy war against the government, would be stormed and taken over by the Pakistani army. But it was with the war on video products that the Red Mosque leaders started their quest. They piled videodiscs and cassettes together to make a gigantic bonfire that was set ablaze by the imam of the mosque, who claimed in my presence that the films were “sinful and lewd.” Perhaps there were some porn films in the pile but, from what I could gather, the vast majority of discs contained Bollywood films with beautiful Indian actresses prominently featured on their covers.

In 2008, Pakistan somewhat loosened its ban on Bollywood films and audiences flocked to theaters to watch long-awaited Indian movies. However, the opponents of Indian cinema still file lawsuits in attempts to bring back the ban.

Indian films are equally popular in Afghanistan. The people of this country have long been some of Bollywood’s greatest admirers, and this affection managed to survive even during Taliban rule, when movies and television were banned. After the fall of the Taliban movement and the return of television to Afghanistan, Indian soap operas became hugely popular. They say that when a new episode is airing, terrorist activity tends to go down. It is hard to say whether that is really the case, but radicals in Afghanistan are also staunchly against Indian cinematography. Still, I imagine they find it difficult to fight Bollywood in the age of satellite dishes. The soft power of cinematic entertainment keeps smashing holes in the armor of traditional societies.

It would be too far-fetched to claim that the Indian film industry will singlehandedly defeat extremism. It is obvious, however, that in regions characterized by a growing confrontation between radical and moderate Islam, Bollywood has already become a trusted partner for the moderates.

Indian Spices for Export

Commercial feature films are financed by production companies, but it is also often the case that the rights to a film featuring celebrities are sold long before it is actually made. Everyone knows that songs play a very important role in Bollywood – and not merely as a decorative element: film soundtracks often account for between five percent and 20% of overall sales. In fact the success of a film is often determined by the popularity of the musical hits featured in it. For that reason a film’s soundtrack is often available before the movie is released.

Commercial feature films are financed by production companies, but it is also often the case that the rights to a film featuring celebrities are sold long before it is actually made. Everyone knows that songs play a very important role in Bollywood – and not merely as a decorative element: film soundtracks often account for between five percent and 20% of overall sales. In fact the success of a film is often determined by the popularity of the musical hits featured in it. For that reason a film’s soundtrack is often available before the movie is released.

The Indian authorities work hard to support the country’s film industry. As early as 1975 the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting set up the National Film Development Corporation (NFDC) in Bombay, where the most popular studios are located. The NFDC’s main objectives are to support and foster modern Indian cinema and provide assistance in harnessing state-of-the-art technologies.

The NFDC also supports non-profit ‘parallel’ Indian cinema, addressing the social issues and real problems faced by Indians. All in all it has helped release more than 300 films in various languages spoken on the subcontinent, including motion pictures directed by Satyajit Ray (the only director from India to be awarded an Honorary Oscar for Lifetime Achievement), Mira Nair, and other renowned filmmakers. Many movies that the organization helped produce have represented India at prestigious international film festivals. The NFDC has also supported the production of a number of foreign films about India, including Richard Attenborough’s award-winning Ghandi.

Indian producers are also proactively involved in Western film productions that also sometimes feature Indian actors, screenwriters, or stakeholders. Merchant Ivory Productions, set up by Indian entrepreneur and producer Ismail Merchant and American director James Ivory, is one of the most salient examples. The company released a number of classics.

Indian commercial films are also finding their way into overseas markets without the aid of government agencies. Plenty of domestic distribution companies, including Eros International and Red Chillies Entertainment, also promote Indian films abroad. The largest – Eros International – maintains a distribution network in 50 countries and operates branches in the US, the UK, and the UAE, among others. Films are shown in movie theaters, distributed on DVD, and aired on cable television.

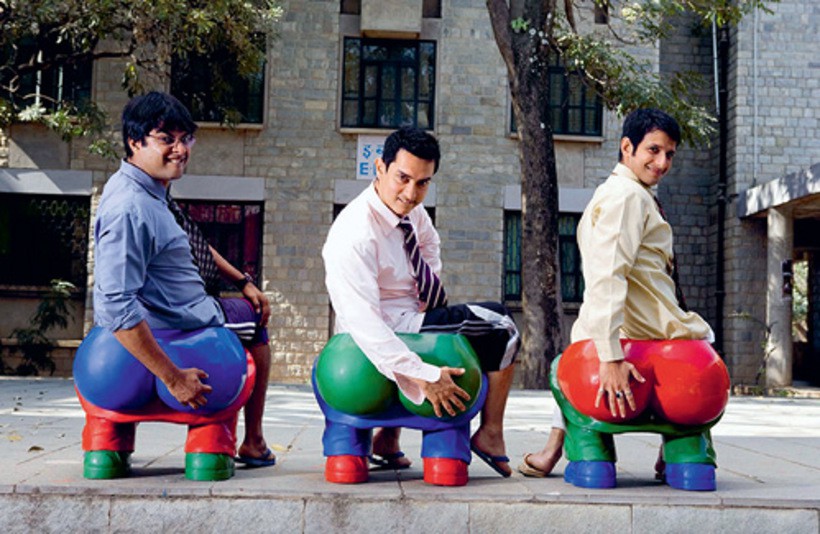

Naturally, the box office performance of Indian films is hardly comparable with that of Hollywood, but the revenues continue to grow steadily, including in overseas markets. For instance, the most popular Indian film in 2013, Dhoom 3 (known in English as Blast 3 and in Russia as Bikers 3) netted $84 million on the domestic market – a great result by Indian standards – and $28.6 million abroad. Another popular picture,

Three Idiots, netted $63 million domestically and $26 million overseas.

Perhaps the most popular category of Indian films, both in India and abroad, are so-called ‘masala’ films (a masala is a mix of hot spices), which combine several genres in one movie, ranging from drama to action – but always with the traditional happy ending.