Role Model

Brazil’s Curitiba is a model of the ‘smart city’ not just for developing, but also for developed, countries. Most of the key challenges that a modern metropolis faces – including environmental, transportation, social and economic problems – were successfully tackled in this city as early as fifty years ago.

Every city with even a modicum of self-respect strives to achieve two fundamental goals. The first is to create a comfortable living environment. It is predicated on tough competition for investment and talent. The second goal is to ensure sustainable development, which requires an integrated model (incorporating economic, social, transportation, energy and environmental aspects) that can guarantee decent living conditions for at least several generations of residents.

As opposed to well-to-do communities in Europe, North America and Australia with their centuries-old traditions of self-government, cities in other regions of the world have to function in a much more constrained environment not just because of their shoestring budgets, but also due to their underdeveloped social and administrative institutions. That is precisely why there are so few cities of this sort in the developing world. However, their number is growing thanks to the modernisation processes that are currently underway in countries in Latin America and Southeast Asia.

Brazil’s Curitiba offers one of the most well-known examples – it managed to create a development model emulated by many cities around the world. Curitiba found a way to resolve a broad range of problems (transportation, economic, social, environmental, etc.) and maintain a high standard of living for most residents.

A revolution in urban planning

Between 1940 and 1980 the city experienced a period of explosive demographic growth caused by the forced industrialisation sweeping through the country, as well as the transformation of its agricultural sector. The huge upsurge in population created a multitude of problems, spurred on by the rapid growth of the vehicle-to-population ratio. With the U.S. experience in mind, the municipality started working on a general plan designed to fast-track the development of private automotive transport and high-speed motorways. However, by the mid-1960s the expediency of this strategy was being called into question.

The decision taken by the authorities to build a motorway cutting through the city’s historic centre ran into organised resistance from intellectuals and students. The city’s elite went through a paradigm shift, and a group of young architects and civil engineers managed to convince government officials to give up the original plan and adopt an alternative development programme conceived by them. The group was headed up by a 27-year-old urban planning engineer named Jaime Lerner. Together they created an independent urban planning research institute (the Instituto de Pesquisa e Planejamento Urbano de Curitiba – IPPUC), mandated to develop key principles underlying the city’s development strategy, and its general plan. Soon after, following a cabinet reshuffle organised by the military junta that was running the country at the time, Lerner himself was appointed the mayor of Curitiba.

On the Monday morning, when supporters of the ‘automobile party’ brought their lorries to break down the roadblocks, they were stopped in their tracks by a group of several hundred children drawing pictures on the pavement. The drivers were forced to beat a retreat. Since that time children draw pictures on the pavement every weekend in what has become a tradition, even though the rights of pedestrians have long been safe

The new strategic plan adopted in 1965 was based on one key idea – to integrate three systems: the street and road network; public transport; and land tenure and development. Their development was to be interlinked depending on the city’s economic, social and environmental needs. This model, coupled with the urban development plan, produced five pivotal elements referred to as ‘structural corridors,’ along which the city’s further growth was to be concentrated, turning it into a predictable and manageable metropolis while gradually building up its transport infrastructure. Thus, Curitiba was to acquire a skeleton to be used for the targeted planning of ‘centralised functions’ (e.g. business, commercial and cultural).

The new regulations governing land tenure and development aligned the concentration of population with the transport capabilities and the number of storeys in residential housing facilities. Maximum density in newly constructed facilities was only permitted within and along the structural corridors; they would become accessible on foot from express bus stops. The city’s remaining territory, located farther away from these main arteries, was to be allocated for medium- and low-rise buildings.

Instead of launching into risky and financially ruinous ‘big projects,’ the city’s administration prioritised a range of concurrent, well-coordinated, and original small-scale initiatives that offered greater savings and relied on local resources and market mechanisms. This approach came to be known as ‘urban acupuncture.’ Transport and land tenure, hydrology and landscaping, education and healthcare, waste management and the eradication of unemployment and crime – all were treated as interlinked elements forming part of an integrated project objective.

The successes achieved by Curitiba’s administration over a relatively short period of time can be explained by several key factors. The professionalism of the city’s executives played a huge role. Acting quickly and efficiently they managed to streamline the work performed by various entities involved in the process of urban development. Moreover, the city’s elite (both the entrepreneurs and the government) managed to reach an important consensus both with respect to the overall 1965 General Plan and selected municipal programmes. Thus, despite a fledgling civil society, the most educated groups in the population were given an opportunity (albeit not entirely equal) to have a role in the city’s governance.

Fighting traffic jams

Lerner’s first steps as mayor were to reform the transportation system and improve the state of the environment. One of the key principles enshrined in the 1965 General Plan was the priority given to pedestrians over motor vehicles, which at that time was seen as a revolutionary step not just in Brazil but in Western Europe as well. This principle provided for a radical improvement in the public transportation system while simultaneously restricting the rights of car owners despite the high vehicle-to-population ratio. (Today the ratio stands at 600 vehicles per 1,000 residents.)

Buses, which could rely on the existing road infrastructure, were selected as the primary means of transport. The cost of one kilometre of dedicated bus lane proved to be 50 times cheaper than that of an underground rail system, while its capacity approximated that of a modern tram, thanks to custom-made models with a longer body. This bus lane backbone was used to gradually develop a range of routes of various calibres, from express to local buses.

The operator of Curitiba’s public transport network (Rede Integrada de Transporte – RIT) is a public company that contracts private companies – the owners of the bus fleets which actually carry the passengers. The municipal authorities coordinate their activities and finance the construction and operation of infrastructure.

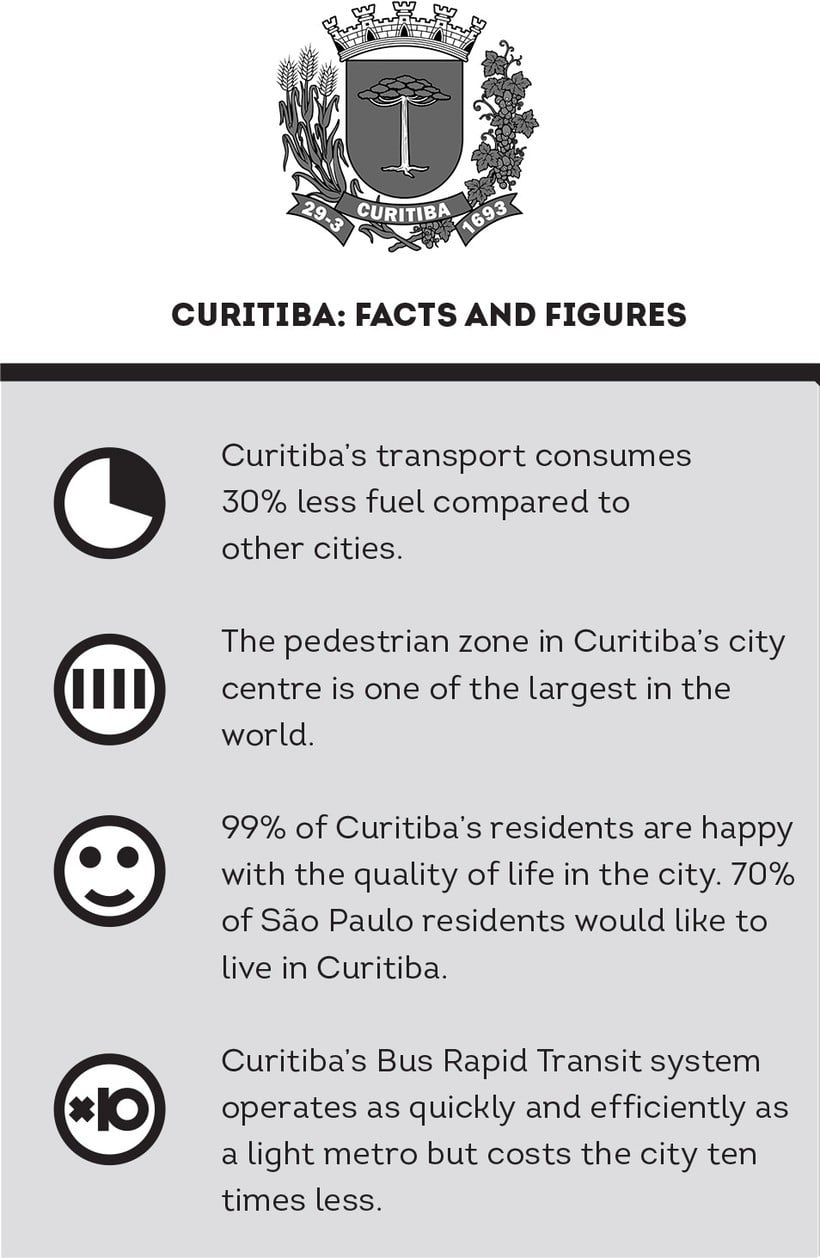

In addition to a significant improvement in the quality of transport services, this approach offered great environmental benefits. The well-organised network of roads and public transport required 30% less fuel compared to other cities. Curitiba’s experience of building dedicated bus lanes has long become textbook material, replicated in different areas of the world – from Ottawa to Mexico and from Bogota to Bangalore.

Green light for pedestrians

Starting in the 1970s, each successive city administration – regardless of political affiliation – was mainly concerned with environmental policy. Even during junta rule, when Brazil tried its best to attract investment into industrial production, turning a blind eye to any hazardous side effects, the construction of new plants in Curitiba was subject to strict environmental safeguards.

Back in the late 1960s the city had virtually no green areas, bodies of water, or well-developed public spaces. Statistically, each resident could enjoy as little as 0.5 square metres of vegetation. Therefore, the city administration focused predominantly on areas located in the risk zone (mostly in floodplains and lowlands) that required immediate attention. In parallel they had to fight against illegal squatter developments on flood-meadows, and often resorted to tough measures. Squatters were evicted from the flood-lands. Linear parks were built along the banks of the rivers, which not only served to expand the territory of the ‘lungs’ of the city but also helped to regulate the streams collecting excess water during the rainy season, preventing soil erosion.

Concurrently with the landscaping improvements the authorities approved a new set of development regulations whereby any newly constructed residential facilities were to occupy no more than 50% of the plot of land on which they were built. Gardening was incentivised through tax benefits for owners of parks and gardens. This proactive and rational environmental policy yielded some tangible benefits: by the early 21st century Curitiba boasted over nine thousand hectares of vegetation (one fifth of the city’s territory). Over a period of 20 years, 30 parks have been built from scratch and 1.5 million trees have been planted, while the proportion of landscaped areas on a per capita basis has increased nearly a hundredfold.

The well-organised network of roads and public transport REQUIRED 30% less fuel compared to other cities. Curitiba’s experience of building dedicated bus lanes has long become textbook material, replicated in different areas of the world – from Ottawa to Mexico and from Bogota to Bangalore

Along with the parks, improvements have been made in the city’s streets and squares. Curiously, this process began with what nearly became a crime story. During one weekend in the winter of 1972, a section of 15th of November Street was converted into a pedestrian zone. This operation had been prepared in full secrecy and took literally 72 hours. Even though the mayor’s office had wanted to bring the local residents on board to help improve the city, all preliminary work had to be done quietly and within particularly tight deadlines amidst some serious concerns over potential violent resistance from street vendors and the gangsters who offered them protection. The latter decided to try to win the street back by force, but the municipal authorities dealt a preventive blow. On the Monday morning, when supporters of the ‘Automobile Party’ brought their lorries to break down the roadblocks, they were stopped in their tracks by a group of several hundred children drawing pictures on the pavement. The drivers were forced to beat a retreat and the municipality celebrated its first victory – one that also brought some added benefits: The new pedestrian street provided an enabling environment for commerce. Since that time children draw pictures on the pavement every weekend in what has become a tradition, even though the rights of pedestrians have long been safe.

The newly created pedestrian zone served as an impetus, pushing the city’s government to put into order the entire historic centre, thus helping it escape the fate of other large cities in Brazil that ended up defaced by development fever in the 1960s and 1970s. Even though in terms of its artistic value Curitiba’s old town may lag behind such pearls of colonial baroque as Olinda or Ouro Preto, its immaculate state is exemplary.

In parallel with the landscaping efforts and other improvements, the city managed to stumble upon an ‘outside-the-box’ solution to its waste management problem. The mayor’s office found a way to convince city residents to recycle rubbish by both raising their awareness (starting in kindergarten) and providing a financial stimulus. The municipal authorities offered the city’s low-income residents a chance to exchange their waste for food and essential commodities. They used a similar approach to clean up bodies of water and public spaces. Thanks to a closed-loop cycle, the administration managed to cut its costs by more than half.

A city that’s socially responsible

The development of a settlement cannot be called sustainable if its economic and environmental achievements are marred by deeply rooted social problems. Where the rights of particular groups of citizens are infringed upon, or there is economic or cultural stratification, or the society suffers from other ills, one can hardly claim that such a community is particularly ‘sustainable.’

Much has been achieved in Curitiba in this respect. The government’s social policy was designed to create an enabling living environment and ensure that all residents could at least enjoy equal opportunities if not equal benefits. Naturally, universal well-being is an unrealistic proposition; however, in the face of the monstrous polarisation plaguing Latin America, Curitiba leaves the impression of a well-to-do city with a population that would hardly qualify as poor.

By the early 21st century, green areas accounted for one fifth of Curitiba’s territory. Over a period of 20 years, 30 parks have been built from scratch and 1.5 million trees have been planted, while the proportion of landscaped areas on a per capita basis has increased nearly a hundredfold

To achieve tangible results the city’s government agencies and social services had to be radically optimised. One innovative approach came in the form of so-called ‘Streets of Citizenship’ (Ruas da Cidadania). These are integrated service centres for citizens, which serve as a one-stop shop for resolving most bureaucratic issues: filing various types of paperwork, paying taxes, registering with the office of unemployment, and much more. In addition to municipal services, such centres include a supermarket for low-income residents where goods are sold at cost, as well as sports facilities and playgrounds for children.

To eradicate illiteracy the city organized new schools and provided so-called ‘mobile classes,’ held in out-of-commission buses moving from place to place. New specialised professional development centres called ‘vacancy roads’ were set up to reduce unemployment. Despite the formal ban on child labour, street children were hired to perform easy work, acquiring new skills in the process. These measures helped to significantly reduce the crime rate and transform Curitiba into the safest metropolis in the country.

To eradicate illiteracy the city organized new schools and provided so-called ‘mobile classes,’ held in out-of-commission buses moving from place to place. New specialised professional development centres called ‘vacancy roads’ were set up to reduce unemployment. Despite the formal ban on child labour, street children were hired to perform easy work, acquiring new skills in the process. These measures helped to significantly reduce the crime rate and transform Curitiba into the safest metropolis in the country.

The city’s administration opted to encourage squatter developments to resolve the housing problem with all construction supervised by professionals. The municipality would purchase large plots of land, put together a plan of the area, lay down the required communications and sell parcels of land to those in need, in so doing offering them a chance to build their own housing and pay for it in instalments. Apart from preparing the land, the city provided additional support by extending in-kind loans, in the form of construction materials and standardised construction designs, as well as offering free specialist advice.

Challenges in the new century

Curitiba’s ‘dirty’ industrial facilities, however, are still dispersed throughout the city, and continue to pose a serious problem. Even though the authorities did manage to group a large portion of the city’s production facilities in a large industrial park, the Cidade Industrial de Curitiba, many plants had been built in adjacent municipalities where environmental protection regulations were not as strict. In addition, the metropolis’ main environmental resources lie beyond the city limit. These include wooded areas and springs, the survival of which are now threatened by urban sprawl.

These problems have not been resolved yet due to a lack of coordination between the various municipalities forming part of the agglomeration. Creating a ‘supra-municipal’ (sub-regional) authority capable of pursuing a streamlined policy in developing the metropolis would be a step in the right direction. However, this idea was strongly rejected by the local elites who fear that their spheres of influence would be re-partitioned. At the same time, the growing ability of local residents to self-organise and develop greater insights into complex issues may well accelerate cooperation between different municipalities and in so doing bring this Brazilian city closer to developing a new and infinitely more complex model of governance.

Vasily Baburov is urbanist and architecture critic.