Soft Power: A Double-Edged Sword?

Bryane Michael, Christopher Hartwell and Bulat Nureev

As shown below (on pages 58 to 60), in the intervening time since it was published, the performance of various countries has changed relative to others, causing a change in the rankings. However, from an analytical standpoint, the more important change that has occurred over the past two years has been an evolution in the thinking about soft power and what it encapsulates. As international attention toward the concept has increased, so too has the understanding both of its components and its limitations.

The purpose of this article is to examine the issue of soft power particularly in reference to emerging markets, but also to explore three specific issues. In the first instance, we examine the role of technology and how it can contribute to extending a country’s influence. Secondly, we look at the constraints of soft power, and how its pursuit may not always bring good results. Finally, with regard to the emerging global conception of soft power, we note how our index will also change to capture these new facets.

Digital Density and Its Correlation with Soft Power

Perhaps the first and most important question is: What exactly do we mean when we talk about ‘soft power’? This elusive and evolving concept can be traced back nearly a quarter of century, and generally refers to the ability of a state to influence the actions of others through persuasion or attraction, rather than brute force or coercion. As we mention in our 2012 index report, “the ability of a nation to influence others tends to be associated with intangible assets such as an attractive personality, culture, political values, and institutions and policies that are seen as legitimate or having moral authority.”† For example, Russia’s encouragement of China and other countries to seek a peaceful solution in Syria, versus the use of military force, is a prime example of soft power.

This ability to influence the world by virtue of who you are (rather than what you do) gives countries like France, the UK, Germany, Switzerland, and Sweden influence in both economics and politics far above what their GDP or even their population size would suggest. Moreover, given the multipolar and complex world in which we live, with the higher visibility of non-state actors and a corresponding increase in the power of multinational companies, hard power has been increasingly more difficult for a nation to exercise. With ‘gunboat diplomacy’ now a less effective (or even counter-productive) tool, and governments around the world facing budget difficulties as a result of the lingering global financial crisis, soft power can be seen as an important substitute indicator of national strength.

But like a tree falling in the forest – only making a sound if there is someone to hear it – soft power must be witnessed to be effective. If a country is successful in business or in achieving higher levels of cleanliness or protecting the rule of law, these successes will not translate into greater soft power unless they are communicated to others.‡ And in an increasingly globalized world, this generally means a need to have as many connections with the outside world as possible. This concept, called ‘digital density,’ refers to the permanent connections to the internet that a country has, a statistic that goes beyond mere landline internet connections to encompass the new digital world of smartphones, tablets, laptops, and multi-purpose technologies. In short, digital density means being connected wherever you are, and countries that are more connected have a higher probability of transmitting influence than those that don’t. This is one big difference (amongst many others) between North and South Korea, for example.

A simple picture of various countries’ internet use can graphically illustrate this point, showing the way that influence builds and passes between countries; internet usage is a good rough proxy for digital density. As the map below shows, there is a high correlation between countries generally accepted to wield greater soft power (and which are, not coincidentally, ranked higher in our index) and internet usage. Even comparatively smaller countries like Estonia and Ukraine have high internet usage, and these countries exercise levels of soft power greater than countries in North Africa, which have correspondingly lower levels of connectivity.

Internet usage provides a proxy for soft power

Soft power describes the way countries and the people in them influence others. In today’s world, the internet represents a key carrier of such influence. Countries ranked higher in our soft power list have more people logging on and using the internet. Compare Estonia and the Ukraine with Argentina and Indonesia: the former are lit up, the latter relatively dark.

Moreover, there seems to be a ‘neighborhood effect’ with regard to digital density and soft power, but not just geographically. While Figure 1 does show concentrations on the map of digital density (especially in Europe) that could then translate to increased soft power, the key point to consider is that it takes two to tango; that is, countries that are plugged into the world both transmit and receive soft power more easily. Countries that are off the grid, as in the heart of Africa or in Central Asia, may not have much soft power globally, but nor are they as influenced by China or Brazil as countries that are connected. It is this reality, that digital density is connected with both transmission and receipt of soft power, which could be a major reason why the concept of soft power is a relatively recent one.

The Perils of Soft Power

While digital density may show how soft power is spread, the reality of soft power and its exercise is a complex issue. In much of the research, and especially in the popular press, soft power is shown as an unmitigated good: a country wants to have soft power, it should acquire soft power, and it improves its standing in the world through the exercise of soft power. However, it is possible that soft power may hurt, as well as help, a country, especially if its acquisition obscures the need to cultivate hard power as well.

Additionally, soft power could lull a country’s leaders into a false sense of security. While being respected abroad may help to smooth over some difficulties, it can also lead to complacency. As the English adages have it, countries should not believe their own press, or rest on their laurels. This reality has been observed both in the trends in our data, as well as in the real-life example of Ukraine.

Soft power, like all power, has its good and bad sides

Soft power, like all power, has its good and bad sides

Ukraine illustrates the paradoxes and prospects of soft power. It

ranks in our top 20, compiled just before the recent unrest. Its soft

power has made it attractive to both the EU and Russia, but has also

made it the cynosure of all eyes, leading to a internal struggle for the

rewards of that power. BRICS economies – and those learning from them,

like Ukraine – must learn how to manage the risks as well as the returns

that soft power provides, both

at home and abroad.

Ukraine has seen an increase in international soft power since its independence in 1991, carefully balancing Russian and European Union interests but drawing on its location, large population, and large foreign émigré base to give the country a voice in international affairs larger than its GDP alone may warrant. Even as the country itself has endured political and economic stagnation, the reputation of Ukraine as a bridge between East and West has survived. Successes such as the peaceful separation from the Soviet Union, coupled with ultimately successful negotiations to denuclearize the country, have also raised Ukraine’s visibility in the world. For example, Ukraine was the first former Soviet republic to co-host the UEFA European Championship, along with the more westernized Poland.

Yet, while Ukraine’s soft power has been directed externally and raised the country’s standing in the eyes of the world, a successive run of Ukrainian leaders could not translate this international standing into tangible successes within the country. Like countries further east that have been plagued with political instability, Ukraine has seen itself undergo two political revolutions, the first leaving it even worse off economically than before. In terms of its economy, the country has stagnated due to corruption, lack of structural reforms, and a reliance on Soviet-era heavy manufacturing – all issues which have led to discontent and a disconnect with the country’s image abroad.

Shang-Jin Wei, Director, the Chazen Institute, and N. T. Wang Professor of Chinese Business and Economy at Columbia Business School

While soft power is to some degree separate from hard power, through the influence of philosophy, religion and culture, it is also dependent on hard power. The world is more likely to pay attention to the soft power of a country already possessing a certain amount of hard power.

Of course, there are plenty of countries whose ranks in combined soft and hard power are above or below their rank in hard power alone. But it is an illusion to think that a country can develop much outsized soft power without having a minimum amount of decent hard power.

Small countries with very limited hard power can have a voice that is more than proportionate to their hard power. Some of the Nordic countries in the last 30 years are great examples of this. Their actions suggest that they also realize that they are more effective when acting in concert with other countries with a lot of both hard and soft power.

While the term ‘soft power’ in English is relatively recent (due to Joe Nye), the substance of the notion far predates the English language term. The Confucian notion of ‘using virtue to govern,’ the associated body of teaching, and the meritorious system of selecting civil servants, are a form of soft power. The culture and political systems of Vietnam, Korea, Japan, etc., were all influenced by Confucian ideas. The influence of Confucianism, Buddhism, Christianity, and Muslim went far beyond their countries of origin; they are powerful early examples of soft power.

Simeon Djankov, Rector, the New Economic School, Moscow, and visiting professor, Harvard Kennedy School

Every time I think of soft power, I am reminded of travelling abroad and being asked by customs officials or taxi drivers which country I come from. When I say Bulgaria, they usually reply “Stoichkov” or “Berbatov,” depending on their age, referring to our best-known soccer players. Some would add “weight lifting” or “wrestling,” referring to the old glory of Bulgaria in producing many Olympic champions in these sports. The reference points are different when you meet people from other professions. They vary from “great opera singers” to “you saved the Jews from the Nazis” to “nice resorts on the Black Sea,” to “the best yoghurt” to “Christo,” the environmental artist who wraps large buildings, bridges and rivers in canvas.

Note that none of these references have to do with national income or economic growth or average life expectancy, the statistics most often used when ranking countries on economic power or national well-being. To me, they best exemplify the concept of soft power – what comes to the mind of people from other countries when they hear your country’s name. There is a clear pattern: Sports and art are truly international due to their global coverage, and hence soft power is highly associated with these two. History, as long as it has made it into the international history books, is next. Success in international politics, usually the domain of large countries, also matters. Science, including Nobel Prize winners, have a disproportionately large effect on forming people’s opinion about a country. Ireland is known as the country with most Nobel Prize winners in literature per capita, and proudly markets itself as such.

There is, of course, a correlation between soft and hard power. Richer countries can afford to spend money on promoting their arts and sciences, on developing sports and memorable resorts. But the correlation is far from perfect – as shown in the Bulgarian example. Hristo Stoichkov, Bulgaria’s soccer legend, belongs to a generation of sportspeople who did their work during the most difficult years of the post-communist economic transition.

For this reason it is useful to capture the main characteristics of soft power and document their development over time. This can tell us a lot about how others perceive us.

The current turmoil in the country, which appears to be split along geographic lines, also appears to be a result of the source of Ukraine’s soft power. The same balancing act between the EU and Russia which gave Ukraine its soft power internationally looks ready to tear the country apart. Like all investments, those in soft power have both risks and returns, but in Ukraine’s case the reality of the country has diverged from its image abroad. Unfortunately, in such a situation, reality always wins.

Ukraine’s trouble in aligning hard power with soft power shows that the latter doesn’t necessarily equal a good image internationally. In some instances, it’s better to be seen and not heard. The case of India is instructive here, as it may benefit both from a relatively lower profile than other BRICS countries regarding many of its foibles – with correspondingly lower-key successes too – and by being the world’s largest democracy. As Alex Lo wrote in Hong Kong’s South China Morning Post last year, “India largely gets a free pass while China is scrutinised with its every move. That’s India’s soft power that Beijing can learn from.” Apart from cultural heritage (Hinduism, Buddhism, yoga, Indian cuisine and so on), it is India’s successful 60-year democratic tradition that helps New Delhi to be regarded as an example for post-colonial and developing countries. Any nation willing to build a transparent and democratic society is more likely to follow India’s footsteps than China’s. And, given the post-Cold War prevalence of free-market democracies, to be accepted as a partner a country should be either democratic or have considerable economic prowess. Finally, by being accepted as democratic, a country is less likely to be sanctioned in the name of spreading democratic values.

Reflecting Changes:

The Evolving Concept of Soft Power and the Agenda for the Future

These different ideas of soft power and how it manifests itself are but a few parts of how the concept has changed and how we understand the channels through which it works. Our original soft power index in 2012 created an academically rigorous baseline, showing which countries had soft power – and why – and we have retained the methodology utilized in that paper for our new rankings. However, given the evolving nature of the concept of soft power itself, along with the heightened awareness of its limitations, our team is striving to revise the index to better encompass more and different ways in which soft power may be quantified. As the very idea of soft power changes, so too must our index.

In this sense, our first attempt at a soft power index was just that, a first attempt, and revisions to it will follow in the footsteps of other well-used indices and rankings. For example, the World Bank’s Doing Business index helps businesses choose countries to trade and invest in, and undergoes periodic revisions to take into account the changing face of a country’s investment climate. Similarly, FutureBrand’s Future Fifteen index is a new, collaborative effort focusing on the future drivers of country brand strength, and as such must also evolve as market conditions change. Our goal is thus to create an index on a par with these other widely used indices, but capturing an aspect of the global business and political landscape that is currently missing.

In the next edition of our Soft Power Index, we will focus on indicators that policymakers (in the public and private sectors) can change, as well as longer-term trends that are the consequence of past choices. We will also be expanding the range of countries we cover, perhaps including the OECD countries and emerging markets. In this way, BRICS countries would be able see how they fare compared to the US or Thailand. We may also include other facets of soft power already captured by other agencies, such as the UN’s Human Development Index, as a way to encompass a broader range of indicators. Finally, we will make better connections with users of the index, particularly through Facebook.

While the revised methodology is currently under development, we predict that the anticipated changes will have an impact on our previous rankings. The most dramatic difference will likely be that smaller countries rise in the rankings. China, India and Russia currently rise to the top of our rankings mainly because of their size – a reality that may be more attributed to hard, rather than soft, power. For the next edition, it would not be surprising if our alterations meant that the BRICS lost their top-tier ranking.

By looking at soft power on per capita and other comparable bases, we hope to make lessons from our index more applicable across all countries – BRICS and non-BRICS alike. The smaller Eastern European countries will probably decrease significantly in rank, while powerhouses in the Middle East (such as the UAE, Egypt and Saudi Arabia) will rise. Third, we will likely measure soft power by what it achieves in financial/economic terms, taking into account not only the benefits, but also the costs – as noted earlier in the case of Ukraine. We will likely measure the way changes in soft power correlate with changes in investment, output, public budgets and trade. In that way, we can measure the costs, risks, and benefits of developing and using soft power.

Conclusion

Soft power represents more than just some fuzzy abstraction, of interest only to academics and international relations majors, but it is still evolving as a concept. It helps countries and companies obtain financial and other benefits without the expense or danger of aggressive policies but, as shown above, it may have its own consequences as well.

By our rankings, the BRICS economies remain key soft-power actors, but it will be interesting to see how recent events and our revised methodology change their position vis-à-vis others. In the future, will China be able to maintain its soft power, given the continuing worries about its economy and its image abroad (especially regarding pollution in its cities and aggressive military moves in the region)? Will Russia be buoyed by the Olympics and Putin’s apparent political successes of 2013, or will events in Ukraine conspire to continue Russia’s relative slide in soft power? Can Brazil emerge as a soft-power player outside of Latin America? Our revised methodology, implemented over the coming months, will allow us to continue to track these developments and stay abreast of this key metric, while incorporating some of the issues that were discussed here.

Evgeny Kaganer, Professor of Information Systems, IESE Business School, Barcelona

The concept of soft power should be treated seriously. Power can be based either on access to resources and control over them, or on convictions and ideas – in other words, on something that people believe in. We cannot fully detach ourselves from the resources that we need to sustain our livelihood. In this hypothetical clash between resources and ideas, it is perhaps the resources that would nearly always have the upper hand. However, when we begin to mix and match resources and ideas in different proportions the situation tends to change: perhaps strong ideas augmented by weak resources can win after all (the Vatican is a perfect example of this). In specific and localized contexts, it is easy to imagine where people would always consider soft power more important than hard power.

I do not think that digital technologies could be considered a stand-alone leading factor of soft power, as they are but a part of a greater global social context. This context consists of a set of ideas that shape human behaviour, and today’s digital technologies in many ways facilitate the ability to formulate and propagate these ideas (or remove technical barriers that hinder the ability to introduce them). Before the digital era, mass media played the role of a mouthpiece transmitting information to the masses, where it was absorbed and became a part of the social environment. The number of these sources of information was limited, as most communication bubbles were isolated from each other; there was no horizontal flow of information. Today such mouthpieces still play a role but there are numerous capillary-like links between them that could be used both with and without these major loudspeakers. After the emergence of social networks, the environment became more transparent, more tools became available with open access, and information started to spread faster. And while anybody can throw an idea into a social network, it is unclear whether this idea will be disseminated. The range of stakeholders who can inject information is virtually unlimited.

If one were to measure the quantitative impact of digital factors in assessing the soft power of a specific country, one would have to start with measuring the level of internet or mobile internet penetration and the percentage of the country’s population using social networks. A more in-depth analysis would require research into the country’s population present in various social networks, broken down by demographics, age, and the amount of time they spend there. An even deeper analysis would focus on the key topics discussed: in selected countries, discussions in social networks tend to revolve more around political factors, while in others, around cultural and sporting events or personal lives.

Bryane Michael is Non-Resident Senior Research Fellow, SKOLKOVO Institute for Emerging Market Studies

Christopher Hartwell is Head of global markets and institutional research, SKOLKOVO Institute for Emerging Market StudiesBulat Nureev is Deputy director, SKOLKOVO Institute for Emerging Market Studies

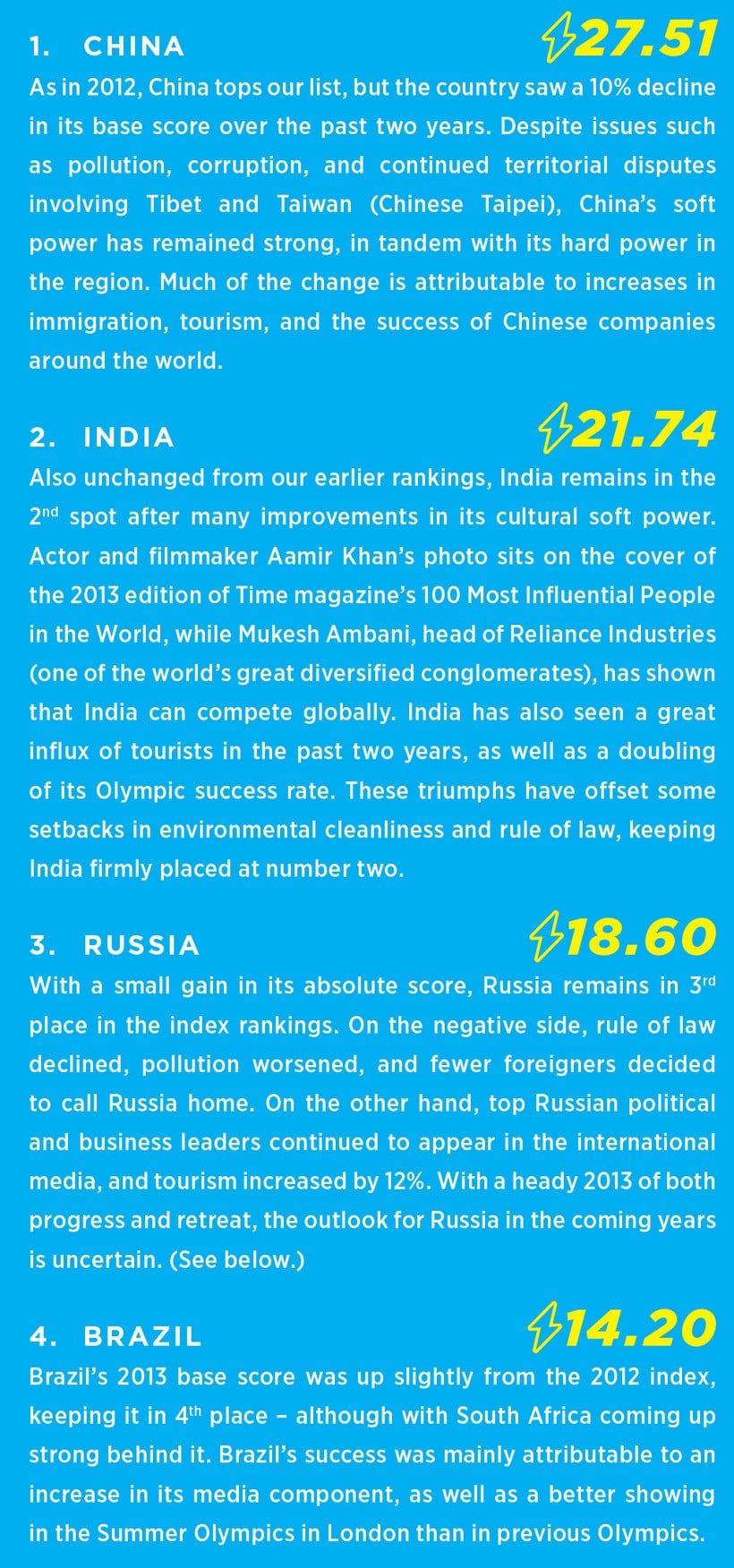

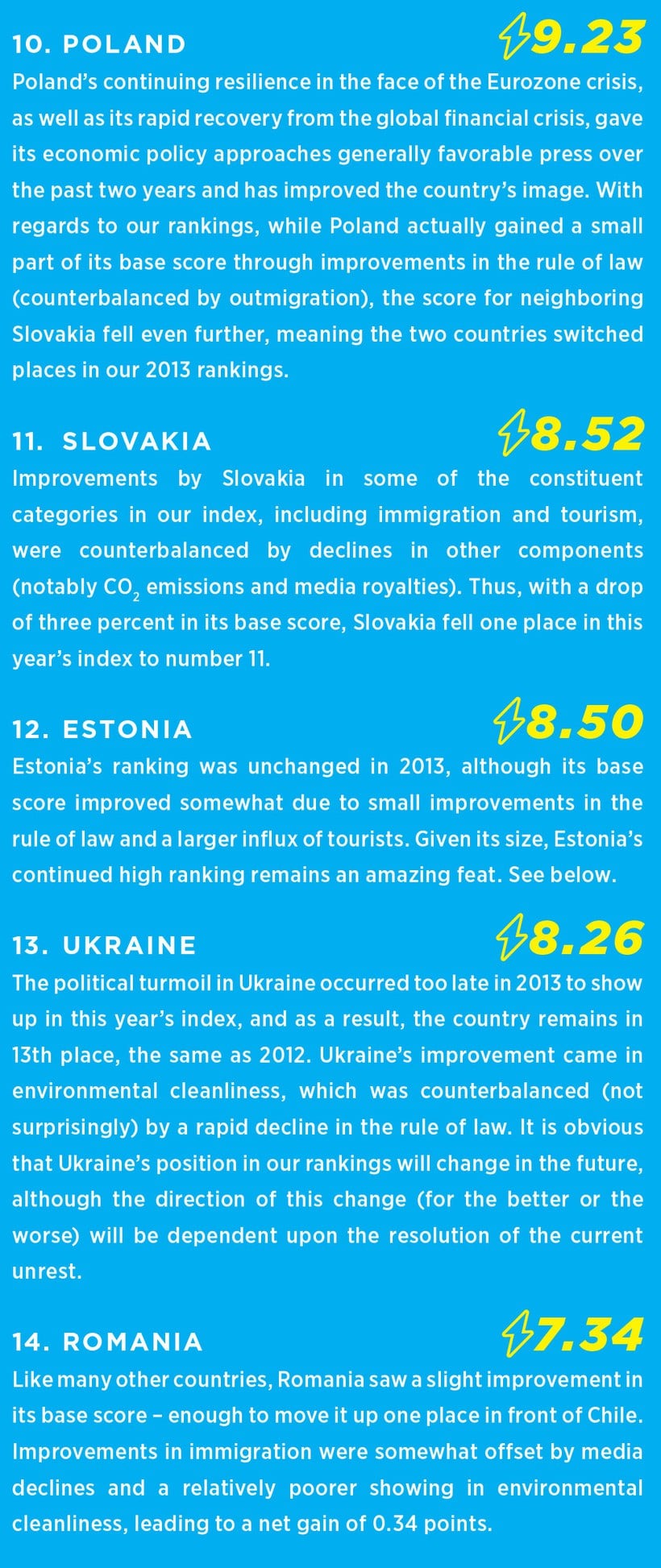

Who Has the Power?

Utilizing the methodology from our original index, but with data updated through 2012 and 2013 (where available), there is little relative change in the top four emerging-market soft power leaders. The emerging economies we study, as a group, increased their soft power index scores; but a steady increase by most countries led to little change in the relative rankings.

China – once again – tops the list of emerging-market countries with the soft power needed to influence world affairs, with India and Russia right behind. Some countries, particularly South Africa, have made large strides in the rankings while also improving their underlying scores; other countries have either kept their relative position despite some improvement in their scores (such as Russia and Hungary), or have seen such a deterioration in their scores that they have moved down the list

(as in the case of Turkey).

Highlights

Russia: A Five-Year Plan for Soft Power?

Russia: A Five-Year Plan for Soft Power?

Although Russia remains in third place in our rankings, the result appears to be in spite of the press coverage of the country. International analysts generally have few nice things to say about Russia, but this could be because, as James Sherr noted in his recent book on Russia’s influence, that the country relies on “brutal” instruments of influence – such as its government, the Orthodox Church, and energy – to drive both hard and soft power. However, even brutal instruments can be utilized to mobilize soft power, as in the generally acknowledged Russian diplomatic success in Syria in 2013, where President Putin’s proposals forestalled military action. Other international controversies, involving Greenpeace, Edward Snowden, the imprisonment of Pussy Riot, and ‘anti-gay’ legislation, have also kept Russia to the fore in news coverage, meaning its soft power is the proverbial bear in the dacha: the country is perhaps helpful, perhaps a nuisance, perhaps dangerous, but impossible to ignore. In the case of Russia, the data seems to support the popular adage that ‘there is no such thing as bad publicity.’

This move towards raising Russia’s visibility has come about through a concerted effort to pursue soft power, with a zest for the game going back to 2007. That year, two appearances by Putin set the tone for Russia’s soft power agenda for the next five years, focusing on the areas that the Russian government felt were ripe for influence. The first was a speech (in English) at the 119th International Olympic Committee Meeting in Guatemala, where Russia won the bid for the 2014 Winter Olympics, an attempt to show the world that Russia was back as an important power player in international sport. This success was reinforced by Russia also being awarded to host the FIFA 2018 World Cup. The second appearance, at the 43rd Munich Conference on Security Policy, set up Putin as diametrically opposed to current trends in the world, positing Russia as perhaps the source of new ideas on hard power in the global order.

These successes, put together with the controversies that Russia has been undergoing, mean a possible hard truth about soft power for the country: the utility of official soft power efforts might be waning. Russia has already grabbed many of the low-hanging fruits of soft power, and is getting only hungrier, with many of its soft power successes coming in reaction to crises in other major powers rather than being truly home-grown. As Harvard professor Joseph S. Nye has noted, “For China and Russia to succeed, they will need to ... be self-critical, and unleash the full talents of their civil societies.” While there has been an attempt to utilize the Russian Orthodox Church as a civil society partner in soft power, the Church’s inherent conservatism has also alienated some of the target audience for Russian soft power.

Thus it appears that Russia’s challenge for the next five years is how to include other civil society and non-official channels in the development of soft power. This might include the continuing modernization and globalization of Russian universities, which are an important way to forge links amongst youth and promote cultural ideas. Additionally, the support and promotion of entrepreneurship rather than a focus on state-controlled national champions would also help Russia to display a soft power that is not just connected with the Russian state. To actually operationalize these approaches, however, will mean less of an emphasis on the one or two megaprojects that Russia seems to rely on, but rather the ‘self-critical’ activities of different stakeholders within society. In this scenario, the Russian state would be more of a moderator – or even absent – rather than leading the charge.

This does not mean there will not be an impact from official sources in the coming years, including the odd mega-project. Of course, the 2014 Winter Olympics in Sochi will surely have an impact on Russian soft power going forward, as they represented an enormous infrastructure investment almost from nothing – brand new stadiums, hotels, sports courses, roads, railroads, airports, and power plants and gridlines – as well as a chance for Russia to show off its prowess in hosting an international event. Similarly, the country’s leap in the World Bank Doing Business Index (from 111th to 92nd place out of 189 countries), to become the highest-scoring BRICS country apart from South Africa (ranked 41st), was a direct result of Russian government attempts to improve the business environment. The question is whether Russia can continue to develop soft power independent of government or, given recent events, in spite of its use of hard power. Influence in the form of soft power is based not on potential capability but on linkages, relationships and interactions; and while Russia may traditionally be more inclined towards isolation, it is better placed than China or Brazil to continue to forge these linkages.

South Africa: Coming into Its Own

South Africa, the smallest of the BRICS in both population and economy size, is still the only African representative in our rankings, highlighting both the country’s successes and the low level of soft power throughout the rest of the continent. Moreover, South Africa’s high levels of soft power are coming at a time when its economy is slowing down; burdened by high levels of unionization, and falling commodity prices around the world, it is unlikely that the country will break free of its relative underperformance (for example, exports only grew by 0.6% annually from 2005-2011).

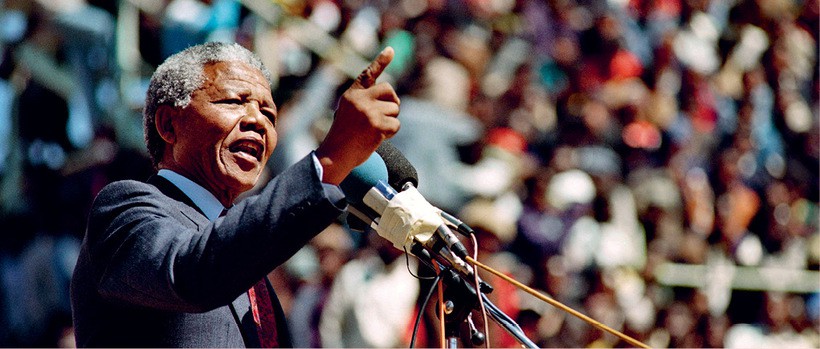

However, South Africa has many positives that are lacking throughout the rest of Africa, and which continue to make it a producer of soft power. In the first instance, South Africa has had leadership – something that has been absent in much of the continent: South Africa’s soft power has been encapsulated in the visage of Nelson Mandela, a leader who was imprisoned under the apartheid regime and, instead of settling scores, embarked on a path to unite his country once again. Indeed, Mandela’s moral suasion was the very embodiment of soft power, and shows how one person can act as an ambassador for a country’s beliefs and ideals.

Mandela was a product of an earlier legacy that has also contributed to South Africa’s soft power: the fact that South Africa was colonized by the British. There is a large literature in economics on the relative benefits of having been colonized by the British versus the French or Portuguese, with the British colonies coming out on top in each instance. The British experience in South Africa left the country both with a more developed legal system and stronger links to the home country than other countries in Africa. (Indeed, Mandela received his undergraduate degree from the University of South Africa, originally created as an examining institution for Oxford and Cambridge.) These links in language, and especially to the British education system, help South Africans to access UK and other anglophone universities, thus aiding their integration into the global community.

Additionally, the collapse of the apartheid regime in the 1990s allowed the country a ‘do-over,’ in that many of its political and economic mistakes were removed as part of a general transition. As part of this transformation, South Africa proved it was able to handle large-scale international events: the 1995 Rugby World Cup (immortalized in the Hollywood film Invictus) saw the hosts triumph, and the 2010 FIFA World Cup was the first time the tournament had been held in Africa. These changes have also helped to arrest the ‘white flight’ that occurred in the 1990s, and South Africa is once again a destination for immigrants.

With the world’s attention once again on South Africa following the death of Nelson Mandela, and given its population of over 51 million people, and its cultural influence in the region, it is likely that South Africa will remain in the top ten of our index for 2014.

Estonia: Small is Beautiful

Estonia: Small is Beautiful

As the smallest country in the top 20, Estonia is the perfect example of soft power being divorced from hard power. With an active military of only approximately 3,000 soldiers, and a nominal GDP ranked 104th in the world by the United Nations, it is difficult to see how Estonia would have any influence in world affairs. But only in a country such as Estonia could the president get into a Twitter fight with Nobel Prize winner Paul Krugman – and only in tiny Estonia could the president get the better of the economist.

Admired throughout the region for its successful transition from communism to capitalism, as well as its relatively better economic performance during the global financial and Eurozone crises, Estonia’s soft power is in large part due to its rule of law and commitment to economic freedom , acknowledged by developed countries when Estonia became a member of the OECD (being the first country from the USSR to join the organization). This has translated into outstanding success internationally in business, although the reality may be that few using Skype today know that it was developed by Estonians (with nearly half of the workforce still located there). Indeed, Skype’s success is another manifestation of Estonia’s risk appetite in business, as Estonia has more business startups per capita than any other country in Europe. The business acumen cultivated in the country has been helped by the presence of world-class academic institutions such as the University of Tartu, which acts as a magnet for students throughout the Baltics and the Nordic states.

Moreover, entry to the European Union, and now the Eurozone, has made travel to Estonia easier, meaning more western Europeans have been able to experience the charm of Tallinn. Estonia is now a popular destination for British young people, given its relatively lower prices. This has gone hand in hand with Estonia’s cultural exports to the world, including a win in the 2001 Eurovision Song Contest – the first by an ex-Soviet country. It appears that, on a per capita basis, Estonia has the largest amount of soft power in our index, a trend that is likely to continue into 2014 and well beyond.