The Selected 15. The Winning Strategies of Russian Entre-preneurial Champions

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Entrepreneurship in Russia is generally overlooked. Indeed, the country – so strongly associated with natural resources – is not traditionally viewed as a welcome environment for dynamic, private business. Yet the private sector in Russia that emerged almost 25 years ago continues to grow rapidly, and a great deal of companies have emerged as new market leaders.

However, entrepreneurship is not only about starting up new companies, but also about the entrepreneurial culture and spirit that help businesses continuously reinvent themselves and exhibit top performance over the long run. IIt is entrepreneurial companies with a proven track record such as these that we have set out to identify and study in our research. The goal is to understand what strategies have led to their success and what challenges they face going forward.

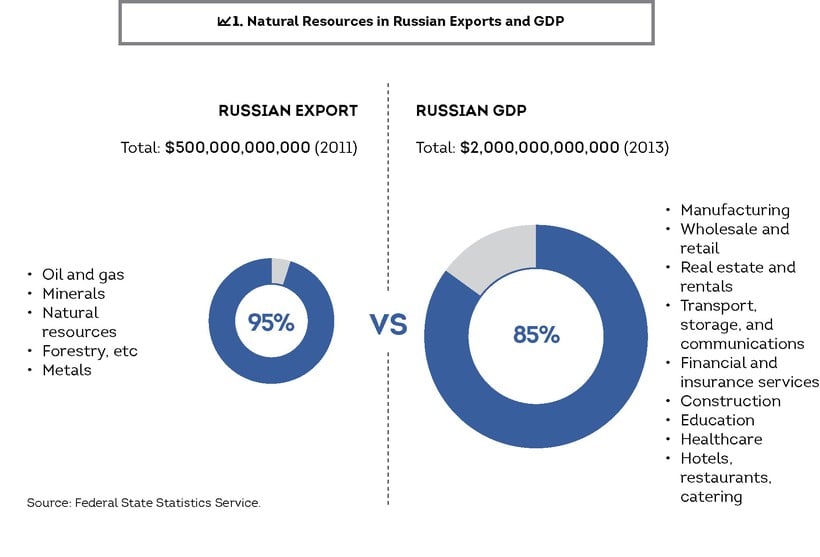

Successful private companies in Russia are easier to find than one might think. While industries related to natural resources constitute almost 95% of Russian exports, they actually account for roughly 15% of Russia’s GDP. Remarkably, the remaining 85% is attributable to industries that have nothing to do with natural resources – and this is where Russia’s new, dynamic, and entrepreneurial businesses can be found.

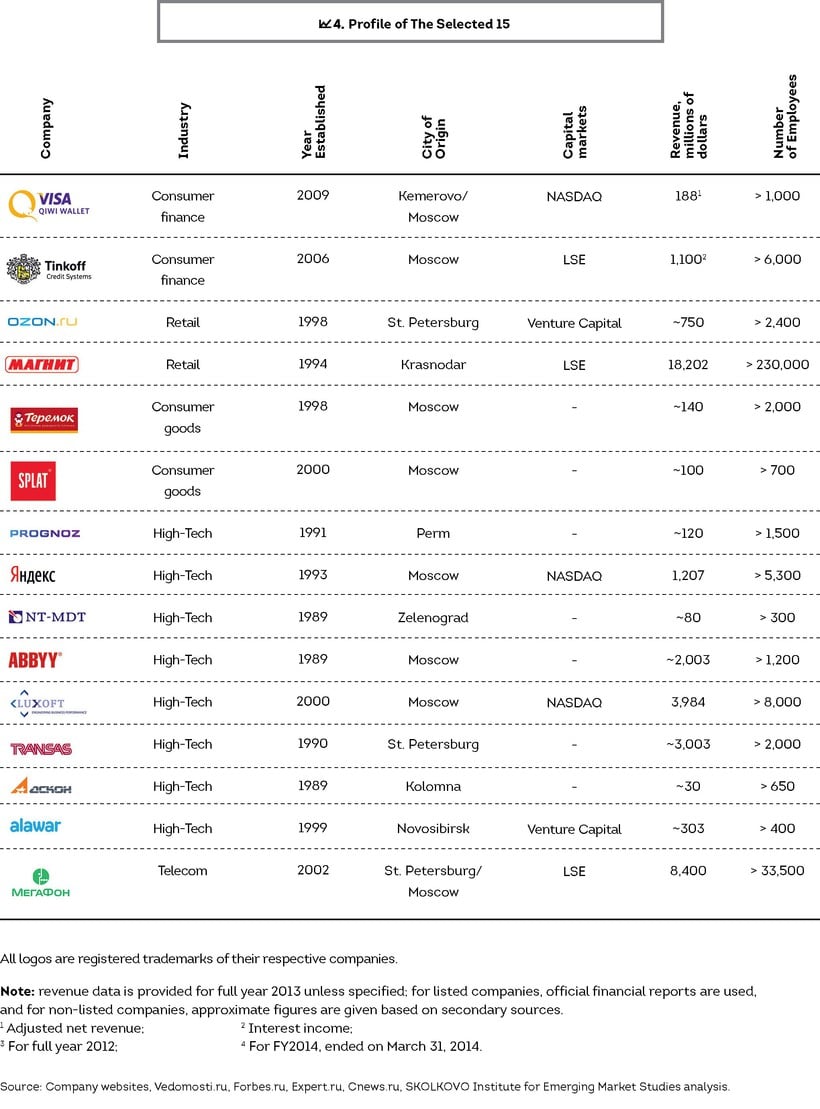

This study showcases 15 companies from Retail, Consumer Goods, High-Tech, Consumer Finance, and Telecom. These companies have grown to outperform, or at least challenge, international players not only in Russia, but also in the global marketplace. The study finds that the success of these companies is attributable to their ability to address challenges or leverage market factors that are specific to Russia. They then establish themselves in the market and develop a competitive advantage vis-à-vis other rivals.

Local Offering Leaders leverages a deep understanding of Russian consumers and their shifting needs to create tailored offerings. Best Adaptors develops unparalleled operational capabilities to tackle Russia’s infrastructural deficiencies and lack of reliable outsourcing options by building in-house competencies or eliminating the weakest operational links. Global Niche Leaders taps into the local pool of highly qualified technical professionals to develop innovative offerings for a global marketplace. Global Citizens jump-starts their growth in Russia and then extensively globalizes not only their sales, but also their operations.

These four strategies have worked well considering the challenges of the Russian economy, but will they help to sustain competitive advantage in the future?

With consumers becoming increasingly demanding, competition intensifying, and economic conditions worsening, companies experience a growing pressure to reinvent their strategies and approaches. Today, the strategic repertoire of these companies is quite limited and primarily focused on product innovation, brand identity, and distribution networks. In contrast, strategies that are underpinned by creative business configurations and take into account evolving client needs and shifting market conditions are often overlooked. It is, therefore, a decisive moment for many of these companies. Now that they are established market leaders, they must continue to think entrepreneurially in order to find new sources of growth in an increasingly competitive and challenging marketplace.

INTRODUCTION

It has been almost 25 years since Russia transitioned to a market economy in the 1990s. The transformation of the economy opened up previously non-existent opportunities for new businesses and ventures. The Russian private sector reacted quickly, promptly filling major gaps left behind by the state-run economy, particularly in serving end customers. Growing consumer appetites, the expanding middle class, and rising disposable income additionally contributed to this trend. TThe new economic environment also opened a gateway to the world for young companies, in the form of access to capital, markets, and technologies. As a result, the last two decades have seen the rise of many new dynamic firms with not only domestic, but also international ambitions.

Nevertheless, little is known about entrepreneurship in Russia. For a long time, it had been largely overlooked as something happening in parallel to the main developments in the Russian economy and viewed as a side effect rather than a driving force. Meanwhile, Russia’s image continues to be defined primarily by natural resources. Indeed, Russia stands high in global oil, gas, coal, metals, forestry, and other commodity export rankings. These industries collectively account for almost 95% of Russia’s $500 billion in exports. What is less known is that their share in the country’s $2 trillion GDP hovers around 15%. This is according to Russian Federal State Statistics, which is sometimes criticized for its transfer pricing mechanism; however, the World Bank gives a similar number of 18.7% in its estimations, which are based on resource rent. (Federal State Resource Statistics, 2013; World Bank 2012). What is important is that up to 85% of the Russian economy comprises industries with no relation to commodities or natural resources (see1). Arguably, it is this 85% where the contribution of newly emergent private firms is most significant.

While there is no intention of conducting a comprehensive study of all private companies that comprise this 85%, this project seeks to showcase real-life stories of the entrepreneurial heroes of the past two decades.

The project’s goal is to provide fresh insights into the lesser known but vibrant stratum of dynamic, competitive, and innovative Russian companies, focusing on their success stories, winning strategies, and the challenges they face going forward.

The story of how these companies became market leaders is particularly remarkable as evidence of positive economic forces at work within Russia. While the Russian economy still faces a number of well-documented and persistent challenges, there are important positive developments taking place nationwide that can be attributed to the success of companies such as these.

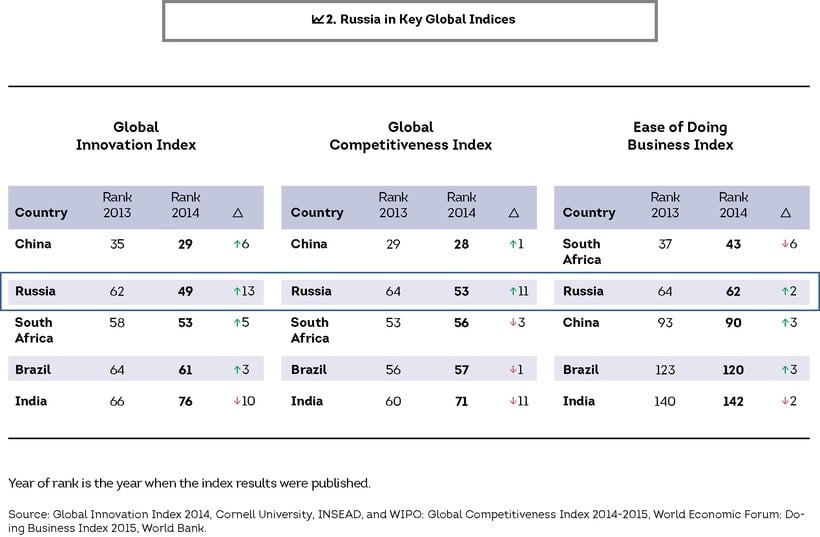

One of the major highlights is that Russia has been continuously improving its position in prestigious global rankings such as the Global Innovation Index (developed jointly by the Johnson Graduate School of Management at Cornell University, INSEAD Business School, and the World Intellectual Property Organization), Global Competitiveness Index (developed by the World Economic Forum), and the Ease of Doing Business Index (developed by the World Bank) (see 2). Among its BRICS counterparts, Russia is the leader in terms of how it has improved its relative position within these three rankings. In the Global Innovation and Global Competitiveness Index, Russia is second after China. In the Ease of Doing Business Index, Russia has left China far behind.

The results of these indices reinforce each other. The Innovation Index and Competitiveness Index tout Russia’s human capital as its key strength. Russia has the world’s highest tertiary education enrollments with a high proportion of students going into science and engineering, combined with a large workforce of researchers producing a significant number of domestic patents and utility model applications. As a result, Russia performs fairly well in technological outputs of innovation and – remarkably – shows a positive record in online creativity.

In the Competitiveness Index, the level of productivity establishes the level of prosperity that can be attained by the economy. According to the report, such factors as size of the market, macroeconomic environment, higher education and training, health, and primary education drive Russia up in the competitiveness rankings. Russia has also implemented a number of effective reforms to ease the terms of doing business. These primarily concern the notoriously troublesome property registration and electricity market. Yet despite these effective reforms, there is still plenty of room for improvement in regulatory environment, quality of institutions, and market terms.

In the Competitiveness Index, the level of productivity establishes the level of prosperity that can be attained by the economy. According to the report, such factors as size of the market, macroeconomic environment, higher education and training, health, and primary education drive Russia up in the competitiveness rankings. Russia has also implemented a number of effective reforms to ease the terms of doing business. These primarily concern the notoriously troublesome property registration and electricity market. Yet despite these effective reforms, there is still plenty of room for improvement in regulatory environment, quality of institutions, and market terms.

While this leaves space for informed policymaking initiatives and targeted efforts to increase efficiency of regulatory agencies, successful individual businesses can themselves serve as engines of growth that drive Russia’s innovation, competitiveness, and market terms. Rather than being imposed top-down by the state, these changes are being effected bottom-up. It is examples of these businesses that the report aims to study.

The stories of these companies are particularly remarkable because, ultimately, they have the power to shape the broader landscape of doing business in Russia. Their positive examples inspire young entrepreneurs; their increasing lobbying power challenges the traditional agenda of regulators and policymakers; and their strong market position shapes – and sometimes even creates – the industries in which they operate.

Altogether, this makes the study of such companies a thrilling and insightful dive into what makes these new Russian entrepreneurial leaders so successful.

This report consists of the following chapters. Chapter 1 provides a review of the methodology used in the selection of these companies as well as a general approach to the research. Chapter 2 takes a deeper look at the market strategies of the companies under investigation and analyzes the key factors that led to their success. Chapter 3 gives an overview of the challenges the companies are likely to face going forward and highlights innovation as one of the key solutions in overcoming these challenges. The Conclusions review the main highlights of the study. At the end of the report, the appendix provides descriptive case studies of 15 Russian companies that have become market leaders.

CHAPTER 1:

IN SEARCH OF RUSSIAN CHAMPIONS

One of the key aspirations in undertaking this research was to showcase examples of not only established success stories, but also uncover examples of successful companies that may not be as well known. As a general rule, private, entrepreneurial companies that are not dependent on natural resources for their success are considered. Although companies from different industries and of different size are studied, preference is given to mid-size technology firms. The selected companies meet one or more of the following criteria:

- The company is a top performer in its field both domestically and abroad;

- The company has invented a new business model;

- The company has successfully adapted and scaled an existing business model;

- The company has outperformed global players in the domestic market.

As information about private companies is rather scattered and there are no aggregate sources, a great deal of investigative research work has been done. This primarily included qualitative research based on comprehensive analysis of secondary data.

The selection process is structured as an original research study whereby both top-down and bottom-up approaches are deployed. The logic of the top-down approach is that companies of interest are sought within industries that are traditionally most conducive to innovation and competitiveness. The bottom-up approach selects companies based on the given set of characteristics by scanning existing ratings, professional contests, awards, industry news, and other sources.

The selection process is structured as an original research study whereby both top-down and bottom-up approaches are deployed. The logic of the top-down approach is that companies of interest are sought within industries that are traditionally most conducive to innovation and competitiveness. The bottom-up approach selects companies based on the given set of characteristics by scanning existing ratings, professional contests, awards, industry news, and other sources.

Top-down approach

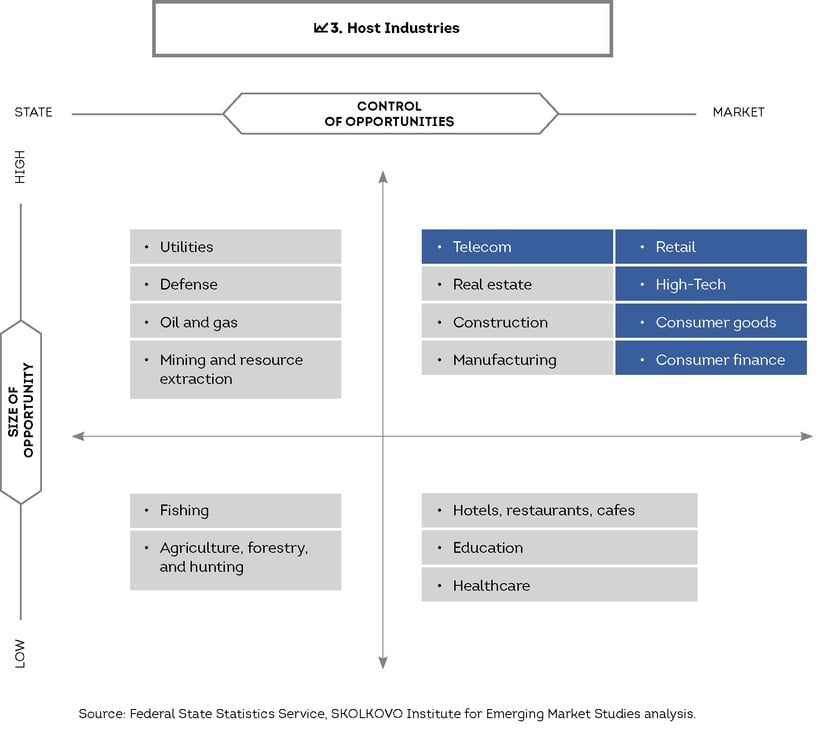

To understand where success stories can be found, we have deployed a number of criteria to identify industries in which we would have the greatest likelihood of finding them. The underlying assumption is that large industries with a dynamic composition of large and mid-sized companies and minimum state intervention also have a higher probability of hosting entrepreneurial and successful private businesses.

Based on a generic set of criteria, we have identified several industries where the competitive environment appears to require creative and innovative strategies to be successful. We examined a number of industries along two dimensions (see 3):

1) The size of opportunity (low or high) associated with the industry’s contribution to GDP, together with its ability to accommodate a critical mass of large and mid-sized companies;

2) Control of opportunities (state or market) associated with the extent of government regulation as well as state involvement in ownership or any other form of control in business.

In addition to the upper-right quadrant (high market, high opportunity), exciting examples of entrepreneurial companies can be found in other quadrants, especially in the lower-right quadrant (high market, low opportunity), where the analysis has shown the emergence of promising start-ups. However, considering the time and scope limitations of this research, we focus only on the upper-right quadrant, where we further apply an additional set of criteria to narrow down the list of industries to consider.

By adding productivity as another screening factor, we concentrate further on industries that demonstrate productivity levels and growth rates higher than average. Not surprisingly, the final list of industries for further consideration comprises relatively new service-rich and technology-extensive areas, primarily driven by consumer rather than business demand. These are fairly competitive markets exposed to global competition and attractive enough based on their size and growth rates. In such a context, companies are under pressure to innovate as a matter of survival. The following industries were selected: Retail, Consumer Goods, High-Tech (including IT), Consumer Finance, and Telecom. As a next step, we moved on to explore companies within these industries.

Bottom-up Approach

The bottom-up selection process started with a compilation of a long list of successful private companies. We focused on three types of sources. First – ratings and contests that specifically reward and distinguish ‘innovative companies’ – including sources such as ‘Tech Up,’ ‘Time of Innovations’ or ‘Top-50 Innovative Companies by ISEM.’ Second – lists of Russian companies that participated in leading international innovation events such as CeBit and BioTechnica (Hanover, Germany), Analytica China (Shanghai, China), and Nanotechnology (Thessaloniki, Greece). Third – lists of resident companies in official ‘innovation clusters’ or ‘incubators’ or companies that have received investments from specialized VC funds. Next, we looked for proof of successful market presence, which helped to screen out businesses in the earlier stages of their lifecycle. The final criterion – degree of domestic market success – was introduced to capture the very interesting group of companies that used technological innovations to overcome important infrastructural deficiencies of the Russian market. Based on a combination of these criteria, we came up with a list of over 100 companies for further study.

Selection

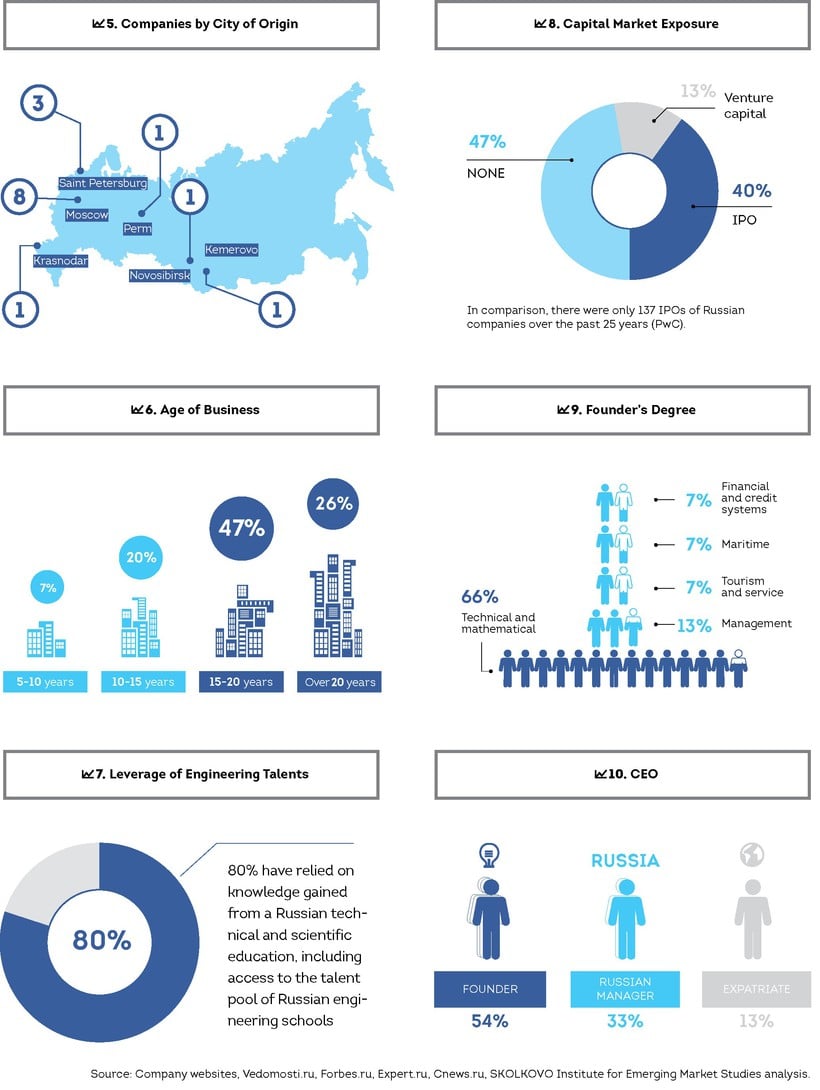

The final stage of the selection process was to merge the findings of the top-down and bottom-up approaches to yield a final list of companies for the case studies. This research approach resulted in a list of prominent as well as lesser-known entrepreneurial success stories. Overall, 15 firms – The Selected 15 – from five different industries were chosen. The companies have been studied based on secondary information from open sources such as company websites, industry reviews, professional databases, and public media. 4 to 10 provide a short profile of the companies and their management.

CHAPTER 2:

WINNING STRATEGIES

The companies in this study, the so-called Selected 15, managed to survive and show outstanding results despite a rapidly changing environment for Russian business. The reasons behind their formation and their strategies for success were to a significant extent determined by local Russian market conditions, which included all the advantages and disadvantages of a young developing market economy.

POOR MARKET INSTITUTIONS. The political and economic crises of the early 1990s left Russia with relatively undeveloped market institutions poorly suited to the new business environment, a relatively high level of unemployment, low regard for legal institutions, low purchasing power of its citizens, and a weak currency. Basic market institutions such as a banking sector, capital markets, intellectual property legislation, and private property protections simply were not available for the Russian business pioneers of the early 1990s. Gaps in legal status, tax, and industrial regulations provided room for interpretation both for entrepreneurs and authorities.

DEFICIENT BUSINESS INFRASTRUCTURE. The Russian economy was restrained, too, by all sorts of shortcomings related to deficiencies in the local infrastructure and the immaturity of markets. These shortcomings included impaired transportation and logistical systems, both of which are crucial given Russia’s vast territory. A deficit of commercial real estate was also a business deterrent. Companies also suffered from insufficient or unreliable supply of professional services and components. Given this background, some industries developed faster, while others developed only gradually, which led to a general misalignment in the overall business environment, hampering the implementation of otherwise proven business models. Some industries were simply absent (like Telecom, Consumer Finance, and High-Tech) or looked quite different from how they look today (like Retail or Consumer Goods). This meant that businesses had to create everything from the ground up, including business models, supply chains, and customer experiences.

NO ENTREPRENEURIAL CULTURE. Besides infrastructural and business environment gaps, Russian culture also acted as an impediment to the development of a vibrant business sector. Entrepreneurship has never been a trait strongly ingrained within the Russian mindset. In fact, for a long time, entrepreneurial activity of any kind has been generally perceived in a negative way, largely as a result of the Soviet legacy. The only business model familiar to the broader population – tracking down scarce goods and then selling them to those who needed them – operated for many years as a shadow part of the Soviet economy. With the dissolution of the Soviet Union, open borders and an inflow of foreign goods created opportunities to make money officially. Perhaps not surprisingly, at least one-third of the founders of the 15 companies included in our study raised initial capital in this way before switching to more ambitious goals and comprehensive strategies.

LACK OF TRUST. The Russian business community is highlighted by a ‘family and friends’ culture of doing business that was based on maintaining a high level of control by a narrow set of insiders. This also meant that less attention was paid to developing best-in-class industry practices, and more to motivating and rewarding top managers. Internal approaches to problem solving (like vertical integration) were more highly valued than the exploration of potential partnership opportunities. From a customer perspective, the general lack of trust in the Russian business world was also an important issue that largely determined consumer reluctance to switch to advanced transaction mechanisms. For example, many people still prefer to pay in cash rather than use plastic bankcards. As a result, Russia even now remains predominantly a cash-based economy. It is due to this lack of trust that all four of the companies in our study whose business models are based on direct contact with individual customers had to adapt their business models accordingly.

These difficulties of the local business environment mostly dissuaded foreign competitors from entering the Russian market and left more space and time for Russian businesses to develop. At the same time, Russian entrepreneurs started to emerge, forced by market conditions to learn quickly and rapidly without any role models. In many cases, they relied on their Soviet education, which placed a strong emphasis on technical and engineering knowledge, and combined that with careful selections from an extensive menu of international best practices, business models, and high-tech solutions.

The Russian mentality and Soviet legacy have also made business rather inward-looking. Unlike Chinese counterparts who have been aggressively entering global value chains, Russian mid-sized companies have mostly disregarded international expansion. Consequently, once faced with market limits, businesses have tended to consider vertical or horizontal integration rather than entrance to other countries with existing product portfolios.

The adverse market conditions, regulatory gaps, infrastructural deficiencies, and lack of business practices make the success of The Selected 15 even more remarkable. These companies have managed to attain market-leading positions in local and even global markets notwithstanding these challenges and often thanks to them. Below we consider their creative strategies to respond to and harness specifics of the local market to their benefit.

Strategies

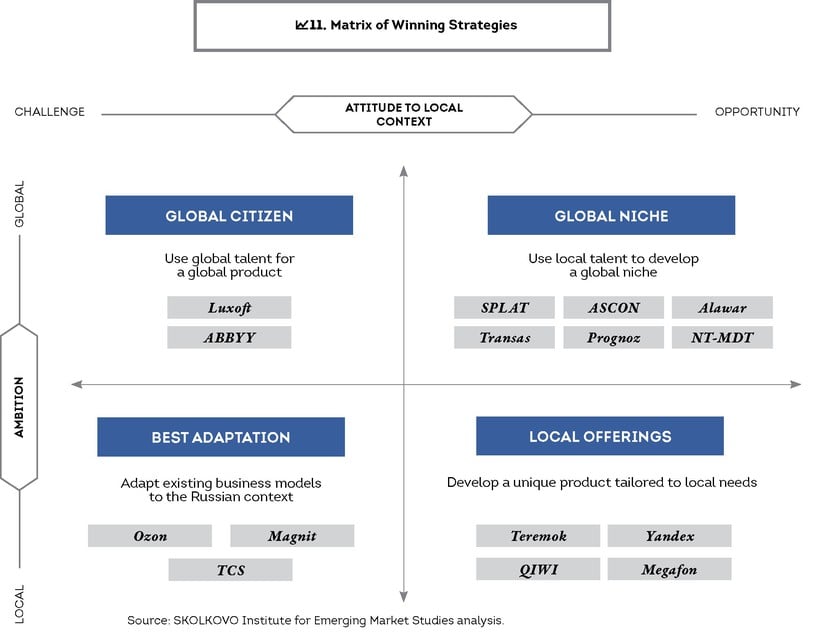

Although each company is unique and it would be impossible to aggregate their success stories into an ultimate winning strategy, we have identified some similarities that can be integrated into a simplified picture representing generic strategies deployed by the companies in this study (see 11).

Our major idea was to separate different approaches that The Selected 15 have undertaken while addressing or taking advantage of the specifics of the Russian business environment. Some considered the specifics of the Russian business environment a challenge and successfully found a way to circumvent them, while others viewed them, instead, as an opportunity to create value and differentiate themselves from competitors.

Additionally, we have considered the approach of these companies to market positioning – either global or local – that they used to eliminate threats or create multiple benefits from opportunities. With all the diversity of the strategies below, there is one common feature for all of them: rapid deployment and a preference for market penetration strategies targeting the long tail of the market first.

BEST ADAPTATION. These companies exclusively focus on the Russian market and use innovative operation strategies to successfully adapt global best practices despite shortcomings of the local infrastructure or the general immaturity of the market. In other words, they have implemented operation models that allowed them to adapt global business models for Russia’s specific local conditions.

Creative operational strategies deployed by the most successful companies in this group helped them to bridge infrastructure and market gaps and build a competitive advantage. The most common solution was ‘in-sourcing’ – building an in-house competence as a substitute for outsourced services. These in-house strategies typically evolved over time, as companies found innovative ways to use digital technology to improve and strengthen existing capabilities. In short, companies used digital technology to maximize performance of an internalized function and then they started to offer services based on this function to the broader market. We have not found any spin-offs, but we believe this can be expected at a later stage as a natural outgrowth of overall market development and growing intensification of competition in the companies’ core businesses.

By applying a best adaptation model, Russia’s largest retail chain Magnit has outperformed not only its local peers, but also global players competing within Russia. It has done this by relying on its in-house logistics and in-house programmers. The company maintains a homegrown, tailor-made ERP solution that is responsible for ensuring sufficient quantities of fresh goods on store shelves. In combination with a strategic decision to focus on small cities first while competitors were targeting more obvious opportunities in large cities, Magnit managed to secure the trust of customers and gain market share, while being almost invisible to competitors. As a result, it was too late for competitors to react once Magnit had already achieved a critical mass.

In a similar way, Ozon also used operational and logistical excellence to become a market leader. Back in 1998, with a Russian postal service that was still quite unreliable and a cash-based economy, people could hardly imagine buying online. To overcome these problems, Ozon – the Russian version of Amazon – developed its in-house transportation unit and rolled out its own network of collection points all over the country, ensuring that people would receive their orders on time and could pay cash on delivery if they wished.

Once Ozon and Magnit’s in-house logistics reached critical mass and high performance levels, the companies started to provide logistics services to third parties. This was not only a way to leverage existing assets – it also encouraged both companies to remain constantly attuned to the competitive needs of the market.

There is also a proven alternative to ‘in-sourcing’ – and that is the removal of the weakest link from the chain. For example, Tinkoff Credit Systems – a consumer finance bank without a single branch – overcame the lack of a viable commercial real estate market within Russia by adapting its business model accordingly. It simply delivers credit cards by courier and provides all customer service online and via call centers.

LOCAL OFFERINGS. These companies also concentrate on the local market and outperform their global and local competitors by offering distinctive value propositions tailored to Russian consumers. Their success has been determined not only by their creativity, but also by a deep understanding of current needs and future expectations of Russian customers.

Qiwi is one of the most prominent examples of how the inefficiency of the local market and a lack of infrastructure can be converted into a promising business opportunity. In a predominantly cash-based Russian economy with rapidly growing cellular phone penetration, many people struggled to keep their accounts funded – payment points were rare and usually very busy. Qiwi installed tens of thousands of cash payment terminals in crowded places like subway stations and malls where people could immediately top up their accounts with cash. This entrepreneurial success is obviously ephemeral, but it helped Qiwi to win the trust of customers, build its brand, and gain a reputable global partner – the international payment system VISA.

Unlike the above, the following set of examples stand out not for their ability to overcome local shortcomings, but for transforming local specifics – such as the Russian language and Russian cuisine – into a platform for building competitive advantage.

As the ‘Russian Google,’ Yandex successfully differentiated its search engine by the efficiency of search in the Russian language and the rapid introduction of locally relevant services, like Yandex.Probki, which helps drivers to navigate through traffic jams in large Russian cities, or Yandex.Taxi, which helps users to hail a taxi in minutes by simply booking the nearest among thousands of cars and hundreds of providers. What made these innovations possible was not just a sophisticated mathematical algorithm created by Yandex, but also the fact that the leaders of this company were sharing the same local environment as their customers.

How local can the global fast food chain be? Perhaps never as much as Teremok – a Russian chain that successfully challenges McDonald’s and Burger King by focusing on traditional Russian blini (pancakes or crêpes) instead of the Western hamburger as a base for sandwiches and rolls. As well, the company has adapted its interaction with customers to reflect Russian traditions and styles, an important complement to the excellent quality of the product.

Anticipating future customer needs was probably the only choice for MegaFon, a late entrant to the Russian cellular market. MegaFon outperformed two other entrenched competitors by prioritizing data rather than voice traffic and focusing on providing fast and reliable connections where people usually use mobile data. The company focused on transportation providers like subways and airplanes, while simultaneously rolling out the network rapidly all over the vast Russian territory. As a result, the company has consistently delivered on its customer-centric motto: ‘The Future Depends on You.’

Anticipating future customer needs was probably the only choice for MegaFon, a late entrant to the Russian cellular market. MegaFon outperformed two other entrenched competitors by prioritizing data rather than voice traffic and focusing on providing fast and reliable connections where people usually use mobile data. The company focused on transportation providers like subways and airplanes, while simultaneously rolling out the network rapidly all over the vast Russian territory. As a result, the company has consistently delivered on its customer-centric motto: ‘The Future Depends on You.’

GLOBAL NICHE. The companies within the Global Niche category are dedicated to world-class single product excellence and outperform their competitors in the global market by developing a strong and constantly improving core product and then offering multiple variations and versatile applications to their customers globally. No matter if a company deploys a cost-leadership or highly focused product strategy – the key success factor is attracting highly qualified people with strong academic backgrounds. As Anatoly Karachinsky, Founder and CEO of Russia’s leading IT systems developer and integrator IBS Group, once remarked, engineers offer Russia the same type of competitive advantage as oil (Vedomosti, 2013). And, given the ability of Russia’s engineers to drive innovation, this advantage has at least the same potential as oil for opening up global markets.

It is the unique mix of superior engineering talent nurtured by the Soviet Union’s best scientific schools and the entrepreneurial drive of specific individuals that are the key factors in delivering a competitive advantage built on world-class performance at a reasonable cost. To document this model, we have studied a number of high-tech players originating in remote cities that are home to Russia’s foremost research centers, with some of them originally being part of Soviet-era military and defense clusters. Alawar, now a top global player in publishing and distribution of casual games, started as a game developer in Novosibirsk, which is home to some of the best engineering schools in Russia. Ascon, sprung from the military-industrial complex in Kolomna, challenges the global leaders in computer engineering and design. Prognoz, founded by a team of economists and scientists from Perm State University, successfully challenges Oracle in the creation of business intelligence applications. Transas, started in the late 1980s by sailors who enjoyed programming as a hobby, is #1 globally in navigation systems today. NT-MDT – #2 globally in sophisticated testing solutions based on atomic microscopes – was founded by researchers from Zelenograd, which is sometimes referred to as the ‘Soviet Silicon Valley.’ These companies are similar not only according to the origin of their success, but also by the attention they constantly pay to the improvement of the core product or technology, and development of integrated solutions around it.

There are other examples of the Global Niche strategy that are similarly based on attracting the best talent available, and using that human capital potential to create premium products. For example, Splat is a premium organic toothpaste supplier with a seemingly endless list of product variations – edible products for kids, non-allergenic products for pregnant women, and products for VIPs featuring tiny gold particles – that successfully challenges such brands as Colgate, Blend-a-Med, and Oral-B in Russia, as well as in 50 other countries around the world.

GLOBAL CITIZEN. In addition to product or service excellence, market acumen, and best-in-class operational performance, the Global Citizen strategy involves setting up multiple locations and hiring talent worldwide – all of which is probably not what one would expect from a Russian company.

Indeed, the examples of the Global Citizen strategy are very rare. Perhaps one of the best examples is Luxoft, which provides offshore software development. The company outperforms low-cost Indian competitors by focusing on developing sophisticated solutions for Western blue-chip companies. Most importantly, the company has service and delivery offices not only in cost-effective locations like Russia or Vietnam, but also in locations with immediate proximity to the customer – such as the U.S. and EU. This is a model the company calls ‘near-shore’ software development.

Another bright example is ABBYY, which initially developed as a Global Niche player; however, the product soon required local expertise in targeted markets. Thus, ABBYY has transitioned to a global citizen strategy based on establishing subsidiaries in foreign markets and then hiring local staff.

CHAPTER 3:

CHALLENGES AHEAD

The strategies built upon the capability to leverage local specifics helped The Selected 15 to achieve their principal competitive advantage and develop a winning value proposition. Moreover, the companies have proven their global competitiveness in the sense that they either outperform or at least challenge their international rivals in the Russian market, and sometimes, even globally. That raises the obvious question as to what extent these strategies can be a source of a long-term competitive advantage: have these companies found their secret ingredient to success or are there challenges ahead that can act as a brake on further growth and possibly even convert their advantages into disadvantages?

TOUGHENING MARKET. The overall economic context in Russia is not as favorable as it was a few years ago. Along with other BRICS countries, Russia demonstrated rapid growth in the 2000s, peaking at a level of 10% annual increase. However, the economy was then severely hit by a global financial crisis that cost roughly 8% in GDP loss and resulted in a steep downturn in 2009. Although the economy picked up rather quickly, its growth has slowed down, demonstrating a lowering rate of increase: 4.3% in 2011, 3.4% in 2012, 1.3% in 2013 (World Bank, 2014) and projections close to 0% for 2014 and 2015 (OECD, 2014). Perhaps the economic slowdown by itself would not be a game-changer for these companies. However, it goes hand in hand with a general maturation of markets and intensification of competition both domestically and overseas. Increasingly difficult access to external financing, especially to capital markets, also places additional barriers for the companies’ development prospects. Profitable global niches become too small to accommodate further organic growth. However, the overall country risk factor influences the attractiveness of Russian M&A opportunities for foreign buyers and can derail diversification ventures, making it altogether difficult for the companies to not only grow but sometimes merely retain existing positions.

NARROWING CAPABILITY GAPS. Over the last decade, business in Russia has experienced the effects of gradual development of institutions and public infrastructure as well as the emergence of greater competition between service providers and other intermediaries in the companies’ value chain. Consumers have also become increasingly demanding and promiscuous. These factors narrow the gaps between market leaders and market laggards and, thus, eliminate the competitive advantage of The Selected 15 that built their success on leveraging market shortcomings or developing value propositions based on market inefficiencies. The improvement of the business environment over the last decade has also attracted new international players, which puts additional pressure on Russia’s entrepreneurial champions.

COMPETING FOR TALENTS. Many of The Selected 15 have achieved their position in the global market based on niche product excellence and a low-cost value proposition. Yet their further geographic expansion and growth in existing markets are likely to require more sophisticated international strategies. Actually, for some companies it might be a matter of survival to transform themselves from successful exporters into truly global players with supply chains reaching across borders and operational hubs scattered around the world. Such transformation asks not only for different skill sets, but also new approaches to talent management. This is particularly alarming considering that hiring and retaining highly skilled personnel has become one of the biggest challenges for Russian companies. It is even more so for those competing in market niches where intellectual capital is paramount. The inevitable increase of overall human capital costs can potentially lead to the erosion of the competitive advantage based on access to low-cost, highly skilled talent.

COMPETING FOR TALENTS. Many of The Selected 15 have achieved their position in the global market based on niche product excellence and a low-cost value proposition. Yet their further geographic expansion and growth in existing markets are likely to require more sophisticated international strategies. Actually, for some companies it might be a matter of survival to transform themselves from successful exporters into truly global players with supply chains reaching across borders and operational hubs scattered around the world. Such transformation asks not only for different skill sets, but also new approaches to talent management. This is particularly alarming considering that hiring and retaining highly skilled personnel has become one of the biggest challenges for Russian companies. It is even more so for those competing in market niches where intellectual capital is paramount. The inevitable increase of overall human capital costs can potentially lead to the erosion of the competitive advantage based on access to low-cost, highly skilled talent.

Innovation Aptitude

The abovementioned observations undermine exactly what helped The Selected 15 to succeed: creative strategies that circumvent or take advantage of the local specifics. Thus, it is conceivable that, over time, current advantages will no longer be sufficient for sustainable long-term development. In fact, they may even turn into a tyranny of past success with strategies that worked in the past becoming less and less relevant for the future and causing the company to contract rather than grow.

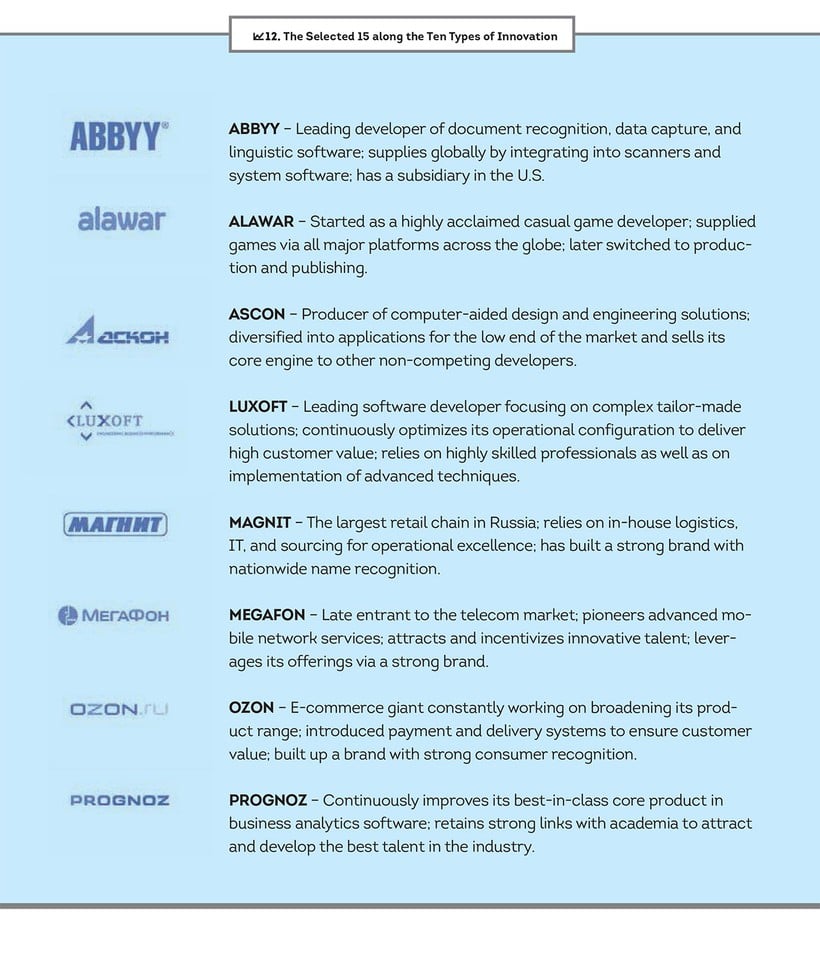

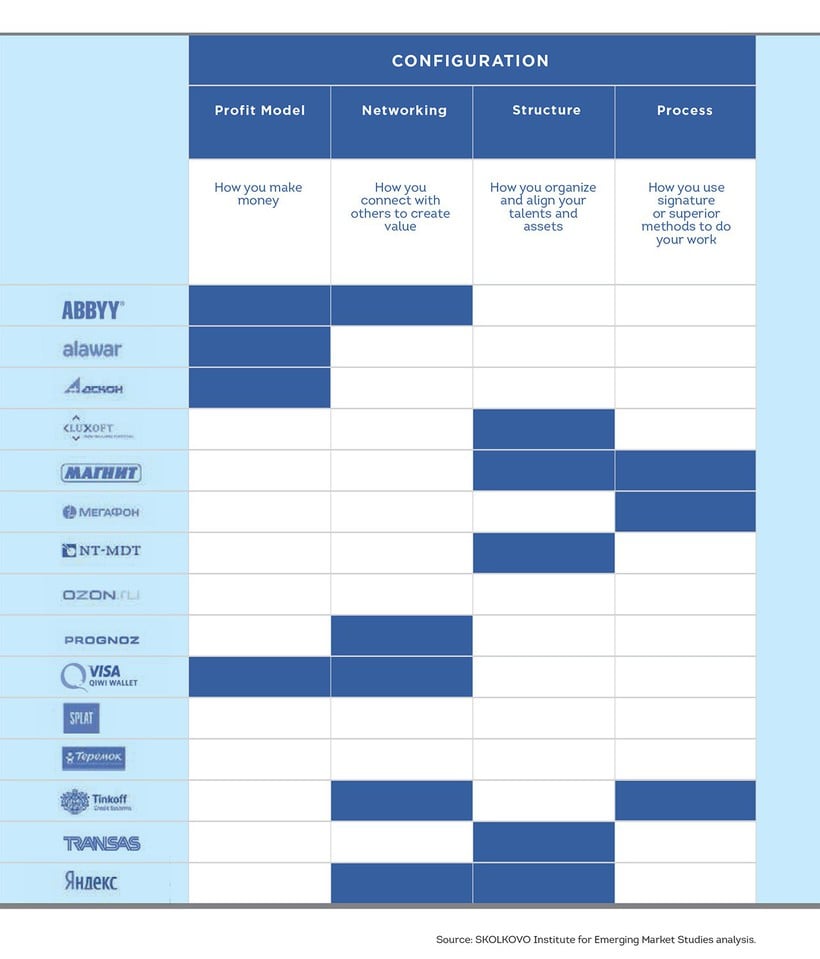

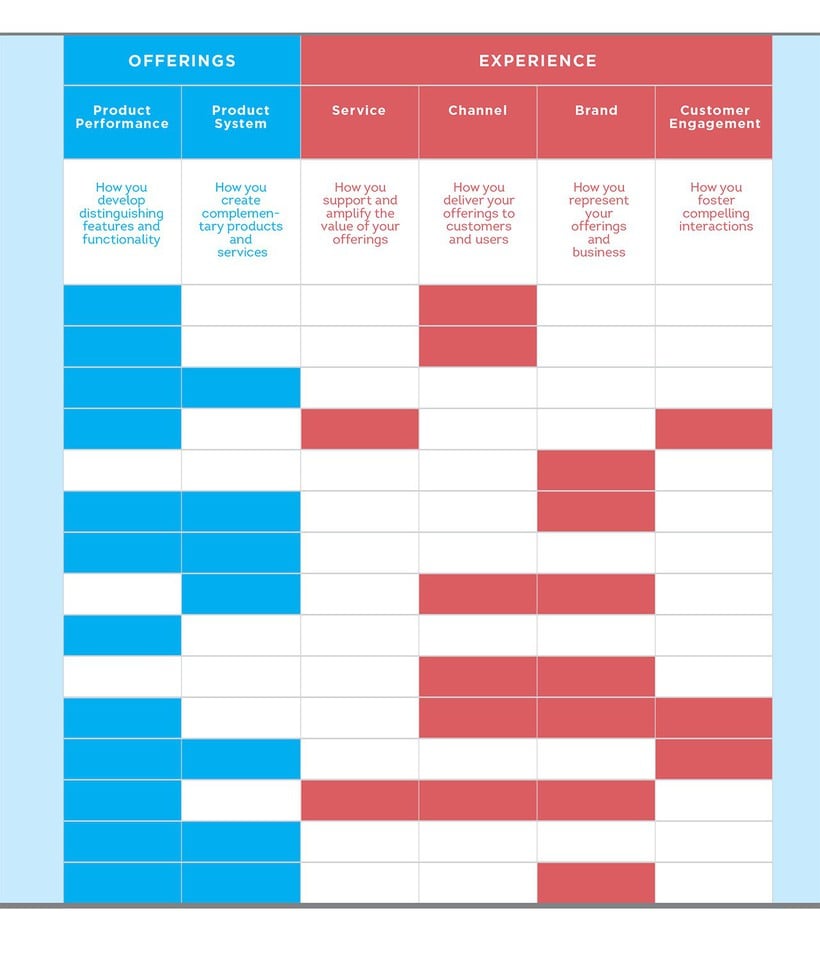

Tougher challenges call for innovative solutions – not creative quick-fixes but an integrated and systematic strategy built around innovative capabilities. To evaluate to what extent The Selected 15 are up to face the challenge, we have screened their strategies through the Ten Types of Innovation framework developed by innovation guru Larry Keeley and his partners (Keeley et al., 2013). The authors define innovation as the creation of a viable new offering and stress that while innovation may involve invention, it actually means many other capabilities, such as a deep understanding of customer needs, building partnerships, and developing creative business models. The framework divides innovations into three categories of innovation types: configuration (focused on how business is done), offerings (focused on a company’s product), and experience (focused on more customer-facing elements and distribution). 12 showcases the evaluation of The Selected 15’s strategies along these types.

What we observe is that half of the companies take advantage of less than a third of their innovation potential. Most underutilized innovation areas are related to services, business models, and customer engagement, while the most leveraged ones pertain to product, brand, and distribution. In other words, the companies tend to focus on types of innovation linked to traditional strategic thinking (e.g., product functionality) while leaving more sophisticated strategic elements untouched.

Generally speaking, this approach to innovation is not uniquely Russian. L. Keeley et al. (2013) mention that focusing on product is a widespread path trap for many companies. However, this strategy is often easily copied and truly successful firms outperform their rivals by mixing and matching differing types of innovation. Greater and more sustainable value can be created through innovative business model configurations and unique types of customer experiences; in comparison, product innovation on its own provides the lowest return on investment and the least competitive advantage.

Putting it differently – most of the companies in this study tend to rely on inside-out strategic thinking that places the product front-and-center while undermining business configuration and keeping customer experience on the periphery. In order to achieve further growth and create greater value in tougher economic conditions, the companies will need to consider the outside-in approach that asks for more sophisticated business systems and puts customers and market opportunities first.

The fact that The Selected 15 collectively use all 10 types of innovation illustrates that the overall Russian strategic landscape is relatively diverse. At the same time, the innovation repertoire of individual companies is quite limited. What once sufficed as a business model would be increasingly challenged in future market conditions. Strategies built on creative exploitation of Russia’s specifics from a decade ago are becoming less effective. The overall business environment is maturing rapidly, further eroding former sources of competitive advantage. Business models built around local specifics only are not able to provide long-term growth, and the companies will be increasingly pressured to introduce more sophisticated types of innovation.

Pushing existing capabilities and rethinking innovative planning will certainly challenge the existing organizational routine and skillsets – a challenge that not every company can handle. Working through the transformation will also require a great deal of multi-disciplinary collaboration and patience. Additional difficulty comes from what once used to be a success factor: more than a half of the studied companies are still being run by their charismatic founders who sometimes rely more on intuition, ‘gut feelings,’ and teams assembled out of networks of friends rather than on disciplined management and professional executives.

Undoubtedly, the future will belong to those companies that manage to develop sophisticated strategies while their existing advantages remain relevant and their current market niches are still profitable. Given the complexity of the transformation and hostile market conditions, there is no doubt that the challenge is daunting. Yet in a rapidly globalizing world, there is just no way around that.

CONCLUSIONS

Despite the country’s well-documented challenges, positive economic forces have been at work in Russia. Private business, which has grown almost unnoticed, is just one such example. No matter how fledgling, entrepreneurship in Russia has made its way through and yielded a multitude of examples of successful and competitive private companies. While generally being off the radar, particularly to the international audience, these companies represent a new generation of Russian business leaders that have made entrepreneurial culture and behavior part of their very core.

The Selected 15 companies studied in this report are remarkable for several reasons. With the majority of them launching in the turbulent 1990s, these companies have managed to survive economic downturns and post outstanding results despite the continuously evolving and often unpredictable landscape of Russian business. The country’s regulatory gaps and infrastructure deficiencies did not impede these companies from developing. In fact, if anything, they seasoned them to be more resilient and creative. Many of the 15 companies highlighted in this report come from industries that did not even exist back in the 1990s, including many in B2C industries. Having established themselves as market leaders, these companies have often played a key role in shaping their industries and, sometimes, even creating them from the ground up.

The analysis of The Selected 15’s strategies shows that these companies have managed to succeed notwithstanding the challenges of the Russian reality but often thanks to them. Despite their different industry affiliations, these companies have one thing in common: an entrepreneurial mindset, which is highlighted by their creative approaches to building and growing their businesses.

The actual strategy that the individual companies have pursued is defined by how they chose to respond to the specifics of the Russian business environment. Some have considered the specifics of the Russian business environment a threat and successfully found a way to circumvent them, while others have viewed them as an opportunity to create value and differentiate themselves from competitors.

The entrepreneurial mindset also explains these companies’ international aspirations. Global ambitions, not to mention global presence, are rarely observed among Russian mid-size companies. There is just no cultural model or business mindset to follow such pursuits and this is where The Selected 15 can become role models for other companies in Russia.

However, the companies’ winning strategies, which once were their strengths, can actually make them vulnerable in the future. Given the relatively undeveloped market conditions that existed in the late 1990s, these companies have done well by focusing mainly on product, brand, and distribution in their innovation repertoire. Yet such inside-out thinking, which puts the product at the center of the business model, might not work well in the face of today’s challenges: unstable economic conditions, growing competition, and increasingly demanding consumers. All of these factors can place serious pressure on the performance and growth prospects of these market leaders. The bigger challenges call for more sophisticated innovations and necessitate outside-in thinking that relies on creative business configurations and enhanced customer experience. Going forward, then, these companies need to continue to think entrepreneurially and deploy creative, flexible, and consumer-centric business models that will help them to overcome the market hurdles of the future.

REFERENCES AND FURTHER READING

1.Chin, V. and Michael D.C. 2014. 2014 BCG Local Dynamos: How Companies

in Emerging Markets are Winning at Home, Boston Consulting Group.

2.CNews. 2013. Overview: IT Market: 2013 (in Russian). Available at: http://www.cnews.ru/reviews/new/2013/review_table/ed22734311cfe6ccbf46b7b7f1d40547ea6c1054/ [Accessed: 18 September 2014].

3.Cornell University, INSEAD, and WIPO. 2014. The Global Innovation

Index 2014: The Human Factor In Innovation, Fontainebleau, Ithaca, and

Geneva.

4.Expert, 2011. Expert – Innovations (in Russian). Available at: http://www.raexpert.ru/researches/expert-inno/ [Accessed: 10 October 2014].

5.Federal State Statistics Service. 2011. Export Structure of the Russian Federation (in Russian). Available at: http://www.gks.ru/free_doc/new_site/vnesh-t/ts-exp.xls [Accessed: 26 November 2014].

6.Federal State Statistics Service. 2013. Gross Value Added By Type of Economic Activity (in Russian). Available at: http://www.gks.ru/free_doc/new_site/vvp/tab11b.xls [Accessed: 26 November 2014].

7.Forbes. 2012. 30 Russian Internet Companies – Forbes Rating (In Russian). Available at: http://www.forbes.ru/investitsii-slideshow/nedvizhimost/79474-30/slide/24 [Accessed: 30 October 2014].

8.Forbes. 2014. 200 Largest Private Companies in Russia: Forbes Rating (in Russian). No.10 (127).

9.Keeley L., Pikkel R., Quinn B. and Walters H. 2013. Ten Types of

Innovation: The Discipline of Building Breakthroughs, Hoboken: John

Wiley & Sons.

10.Korovkin V. 2014. Creators of the Future, BRICS Magazine, No. 3(7) pp. 46-65.

11.OECD. 2014. Russian Federation - Economic forecast summary. Available at: http://www.oecd.org/eco/outlook/russian-federation-economic-forecast-summary.htm [Accessed: 20 November 2014].

12.Park S.H., Ungson G.R., and Zhou N. 2013. Rough Diamonds: The

Four Traits of Successful Breakout Firms in BRIC Countries, San

Fransisco: Jossey Bass.

13.Polunin Y. And Yudanov A. 2013. Fragile Force of Mid-size Business (in Russian), Expert No.20(851).

14.PwC. 2014. An overview of Russian IPOs: 2005 to 2014. Listing

Centers, Investment Banks, Legal Counsels, Auditors and Issuers’

Jurisdictions. Available at: http://www.pwc.ru/en/capital-markets/russian-ipo.jhtml [Accessed: 18 November 2014].

15.Schwab, K and Sala-i-Martín, X. World Economic Forum. 2014. The

Global Competitiveness Report 2014-2015, World Economic Forum.

16.Vedomosti. 2013. Interview - Anatoly Karachinsky, President of IBS Group (in Russian). Available at: http://www.vedomosti.ru/library/news/8923521/inzhenery_takoe_zhe_preimuschestvo_rossii_kak_neft_anat... [Accessed: 26 November 2014].

17.Vedomosti. 2014. Company Directory (in Russian). Available at: http://www.vedomosti.ru/companies/a-z/ [Accessed: 24 November 2014].

18.World Bank. 2012. Total Natural Resources Rents (% of GDP). Available at: http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.TOTL.RT.ZS [Accessed: 26 November 2014].

19.World Bank. 2014. GDP Growth (annual %). Available at: http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.KD.ZG [Accessed: 26 November 2014].

20.World Bank. 2014. Russia Economic Report, No. 31, March 2014: Confidence Crisis Exposes Economic Weakness. Moscow.

21.World Bank Group. 2014. Doing Business 2015: Going Beyond Efficiency. Washington, DC: World Bank.