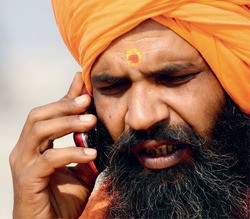

Dancing Shiva with a Phone

Evgeny Pakhomov

Last year’s scandal in India, caused by the sudden blanket termination of 122 mobile communication licenses held by several Indian and international companies – including a powerful local subsidiary of Russia’s Sistema JSFC – once again highlighted the specific risks of doing business in the country. It did not, however, undermine the appeal of the Indian telecoms market, where far more people have access to a mobile phone than to a private toilet.

A Symbol of Divine Status

Telecommunications in India has long enjoyed the reputation of a market that is both highly promising and too prone to scandals. In the late 2000s the number of mobile phone users in this vast country was growing at an unprecedented rate: in some months local mobile operators would sign up 20 million new subscribers. For the country’s young people (more than half of the population is under 30 years of age), a mobile phone has become the equivalent of a sports car to their European and American counterparts – in other words, a status symbol.

The Indian press even wrote playfully that mobile phones should be added to the list of accoutrements that the multi-armed Indian deities traditionally hold in their hands, such as discs, clubs, shells and lotus flowers, positing a premise that not even Gods could do without a mobile phone – let alone mere mortals. That is why the debacle was so high-profile when, in February 2012, India’s Supreme Court terminated 122 2G mobile communication licenses that had been awarded back in 2008. In justifying its ruling, the court stated that the licenses had been issued in a “completely arbitrary and unconstitutional manner.”

Andimuthu Raja, who at the time held the office of India’s Minister of Telecommunications, found himself in the middle of a scandal, accused of the “unlawful” and “illegal” allocation of the 2G spectrum. According to investigators, the public servant had sold telecommunications licenses at too low a price, causing the Indian budget to sustain losses totaling nearly $40 billion. The Minister denied all the allegations, but eventually resigned, and was arrested in February 2011. Soon after, one of his aides committed suicide, and several months later the Supreme Court issued the notorious ruling canceling the licenses in question.

Most local observers believed that internal politics was to blame for the scandal. They claimed that the opposition had constantly accused the government of being corrupt, and had persistently called for ‘ritual sacrifices’ to reshuffle public offices. At the time, India was going through a daisy chain of different scandals, including the infamous case of the misappropriation of funds and padded budgets during the preparations for the 2010 Commonwealth Games, which cost several high-ranking state sports officials their jobs. Another case in point was the sacking of Chief Vigilance Commissioner P. J. Thomas, also initiated by the Supreme Court. This public official was appointed to combat corruption but ended up being implicated in corruption-related proceedings.

The telecommunications scandal turned out to be the most high-profile case, however, since its ramifications went far beyond India’s borders. The 2G license termination affected a number of influential Indian and foreign companies, including Etisalat, Loop Mobile, Videocon, Idea Cellular (in which Malaysia’s Axiata has a stake), Tata DOCOMO (a joint venture between Tata Teleservices and Japan’s NTT DOCOMO), and Uninor (a joint venture between India’s Unitech Group and Telenor of Norway). Sistema Shyam TeleServices Ltd. (SSTL) – the company behind the MTS brand in India – also suffered the consequences, losing 21 of its 22 mobile licenses in India.

Dream Market

The numerous efforts undertaken by the affected operators to appeal the ruling proved to be in vain: all motions to appeal submitted to the Supreme Court were denied. The only thing they managed to achieve was the right to continue their work until a new auction to allocate the spectrum could take place.

SSTL exhausted every avenue in trying to recover the lost licenses, and even escalated the issue to the highest level. The topic was discussed in October 2012 during an official visit by Dmitry Rogozin, Deputy Prime Minister of Russia and co-chair of the Russian-Indian Intergovernmental Commission. In making his case Rogozin noted that, “over the years that the company operated in India, Russia invested nearly $3.2 billion through Sistema JSFC and the State Federal Property Management Agency, turning SSTL into a flagship of bi-lateral cooperation between the two countries in the civilian sector.” He also added that the Russian government was “deeply concerned” by the recent turn of events. According to the Indian press, the issue of the MTS licenses was also discussed during President Putin’s official visit to New Delhi in December last year.

But once again, all arguments and complaints fell on deaf ears. Eventually, however, India did hold a series of new auctions, in March 2013, and SSTL turned up as the only participant. It was awarded licenses in eight telecommunications districts: Delhi, Calcutta, Gujarat, Karnataka, Tamil Nadu, Kerala, Western Uttar Pradesh and West Bengal, at a total price of nearly $665 million.

“SSTL’s operations will now focus on the most prospective regions, servicing 40% of the country’s population, amounting to over 60% of the data market whilst also maintaining 75% of the company’s revenues,” said Sistema’s President, Mikhail Shamolin, in a statement following the auction.

Experts interviewed by BRICS Business Magazine remain convinced that SSTL chose the right strategy in giving up the spectrum without a fight in those regions where the number of subscribers remained at a minimum level. Their loss will not have any critical bearing on the company’s business. Focusing its efforts on priority areas will enable it to improve its competitive edge in a market where unbridled growth has become a thing of the past. It has already managed to capture the main consumer pool residing in cities and many rural areas, so the industry will not see the same dynamic development as it did in the middle of the last decade.

In spite of it all, India’s telecommunications market remains one of the most attractive in the world, as borne out by one curious detail: today, more Indians have access to a mobile phone than to a private toilet. Their numbers are 930 million and 638 million respectively, from a total population of 1.2 billion people. This market, therefore, will predictably see some intense competition – despite the fact that not just politicians, but Indian gods themselves, may interfere at any given moment.

Doing Business in India, alien’s guide

Vsevolod Rozanov

Vsevolod Rozanov

Honest intentions and a full set of the requisite permits are not

sufficient to guarantee that operations in India will go off without a

hitch. Sistema Shyam TeleServices Limited learned this the hard way

when, along with a number of other companies, it lost its mobile

communications licenses last year. But that is not the only lesson the

company has taken from its four years’ experience in India.

When Sistema Shyam TeleServices Limited (SSTL) launched its operations in India in March 2009, the local mobile communications market was peaking: more than 20 million new mobile subscribers were being added every month.

The intense competition, involving more than a dozen serious market players, including several other large international telecoms companies, was one of the most significant factors contributing to the exponential growth of mobile communication services in the country. The hearts and minds of Indian consumers proved to be exceedingly sensitive to the cost of the product on offer, which forced providers to aggressively reduce their prices and expand their geographic coverage. As a result, rates for telecommunication services in India became some of the lowest in the world, with hundreds of millions of local residents covered by mobile telephony and millions enjoying wireless internet access.

SSTL didn’t miss its chance to jump on the bandwagon. In

particular, we managed to offer local consumers several concurrent,

innovative, products. These included the ‘half a paisa per second’ rate

(a paisa is one hundredth of a rupee – approximately 0.016 cents);

prepaid broadband mobile data services; unlimited access to popular

social networks; and many other services. In 2009 SSTL also launched a

broadband service in India under the MBlaze brand, and quickly expanded

the service to cover 350 Indian cities. As to the question of how

popular this move was, statistics tend to speak louder than words:

during our first three years in India the number of SSTL subscribers

went from zero to 1.8 million, while the company’s market share exceeded

20%.

The multitude of problems that companies often have to face in virtually every emerging market tend to be particularly salient in India. Therefore it is critical for any business operating in the country to maintain an optimal cost structure. That is not, however, how it works in practice: given the Indian market’s vast scale and diverse nature, many companies often plan for a quick expansion, which tends to result in excessive costs

Our competitors, however, were not far behind. And then, at a time when the country’s telecommunications industry was going through a period of unprecedented growth, on 2 February 2012 the Supreme Court of India issued a ruling terminating 122 mobile communication licenses that had been issued in 2008, including 21 of the 22 licenses held by SSTL.

This came as a shock to all the market participants, who were clearly not ready to deal with such a turn of events. SSTL was no exception, even though we were confident that we had not broken any laws. The company had come to India with the best intentions, and obtained an official license issued by the country’s government after having completed all of the requisite formalities. None other than the Indian government had ratified our investments in full compliance with the country’s legislation.

Be that as it may, neither the petition to re-try the case nor the appeal to reinstate the license, submitted by SSTL, succeeded in reversing the February verdict. Pursuant to a ruling by the Supreme Court, and after having been rescheduled several times, the new auction – for both GSM and CDMA spectrum bands – finally took place in November 2012. In essence it proved to be a flop: because of the unreasonably high initial price, almost no CDMA operators took part in the event, including SSTL.

Our company participated in the second round only after the Indian authorities agreed to halve the baseline license fee. As a result, we were awarded spectrum licenses in eight telecommunications districts in addition to the one license we still had. As a result, SSTL services today cover an area that is home to 40% of India’s population, making the company one of the top three players in the country’s telecommunications market, which we still genuinely believe to hold a great deal of promise.

Flexibility and innovation

Despite our various troubles and trepidations, there is one important lesson to be learned from our efforts to acquire mobile licenses: if you want to operate in India, you should always be prepared to face the unexpected. After four years in the local market, we now know that any successful business here is predicated on a great deal of attention to the specific customs and characteristics of this vast and diverse country.

For instance, one should always bear in mind that the multitude of problems that companies often have to face in virtually every emerging market tend to be particularly salient in India, especially against the backdrop of its low-quality infrastructure, tough competition, and growing deficit of qualified human resources. Therefore it is critical for any business operating in the country to maintain an optimal cost structure. That is not, however, how it works in practice: given the Indian market’s vast scale and diverse nature, many companies often plan for a quick expansion, which tends to result in excessive costs.

Another typically Indian challenge is the volatile nature of the local legislative framework, which always remains a ‘work in progress.’ Any company operating in India should take this factor into account in preparing its business plans.

Moreover, given the high level of competition in the Indian market, revenues can hardly grow without innovative business models. This is not a whim; it is a bare necessity. Placing more emphasis on variable costs models in every business segment will considerably improve your efficiency.

Finally, it is equally vital to maintain maximum flexibility in

pursuing your business plans. Bear in mind one thing: whatever enables

you to succeed in other markets will not necessarily work in India. In

other words, here you must think globally and act locally, taking into

consideration the enormous size of this country as well as its diverse

and ‘patchy’ population.

Vsevolod Rozanov is President and CEO of Sistema Shyam TeleServices Ltd.,

a subsidiary of Russia’s Sistema JSFC in India.