Local leaders of the developing countries from different sectors to actively argue about their global ambitions

New Graduates, Challengers and Champions

The aftershocks of the recent economic turmoil can still be felt, but emerging markets remain a strong launchpad for successful companies. The strongest and most globalized of them – the world Challengers and world champions – are doing just fine overtaking members of the developed countries club on the world stage, both in terms of efficiency and revenue growth. This is precisely the picture painted by the June BCG report analyzing the situation in emerging markets. BRICS Business Magazine presents an opportunity to get acquainted

with the most interesting of its propositions and conclusions.

The recent struggles of emerging markets (EMs) are so well-known that it can be hard to distinguish the fast-growing trees from the forest. But despite the slowdown in macroeconomic growth, the drop in commodity and currency prices, the crash of equity markets, and the rise of geopolitical risks, the top companies from EMs benefited tremendously from years of compound growth.

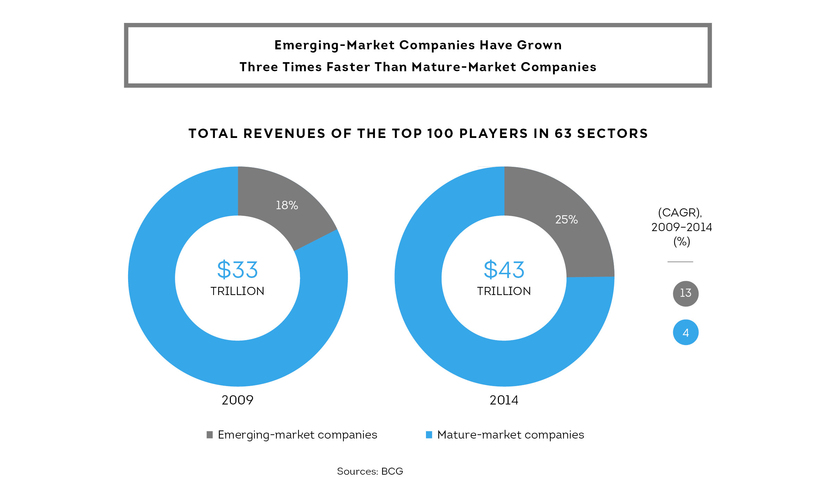

They grew three times faster than their counterparts in mature markets from 2009 through 2014. From 2005 through 2014, the average revenues of the largest EM company in each of 63 industrial sectors expanded from $15 billion to $43 billion. Revenues for China’s Huawei, for example, ballooned to $61 billion in 2015, a 37% increase from the prior year. In IT services, India’s Tata Consultancy Services and HCL Technologies have achieved double-digit growth almost every year.

In sectors as varied as household appliances, construction and engineering, industrial conglomerates, construction materials, and real estate development, companies from emerging markets have captured global market shares exceeding 40%. For example, the three air conditioning manufacturers with the largest market share in the world are China’s Gree, Midea, and Haier.

But the numbers tell only part of the story. What are these companies exactly, and where do they come from? Outwardly, there has been little shift in the industry or geographic mix of the global challengers. Industrial goods is still the sector with the largest number of challengers; among countries, China and India come out on top. This high-level view, however, does not capture many of the undercurrents that are starting to ripple to the surface.

One trend is that resource and commodity companies may have passed their high-water mark. These companies have always made up a healthy share of the global challengers. And they do so in this year’s report as well, accounting for 24% of companies on the list. But between 2014 and 2016, the number of challenger energy companies declined from 13 to 10. And none of the new challengers is solely in the resource or commodity business.

Another shift is the rise of a new breed of consumer companies. The consumer-oriented challengers on this year’s list are moving beyond advantages based on cost and access to raw materials such as palm oil. They include Dalian Wanda, a luxury hotel and resort developer from China, and Discovery, a financial services firm from South Africa.

The new challengers are also appealing to the digital needs of the expanding middle class in emerging markets. Two prime examples are Axiata, a leading regional telecom operator, and Xiaomi, a maker of smartphones. Remarkably, the revenues of device makers from emerging markets grew eightfold from 2005 through 2014, reaching $211 billion. While many device makers are winning with low-cost products, others are increasingly investing in innovation and R&D.

Several other new challengers are likewise emblematic of larger themes. The emergence of China Eastern Airlines and Pegasus Airlines as challengers reflects the rise of air carriers in emerging markets. From 2005 through 2014, the revenues of such airlines tripled, and their global market share rose from one-fifth to one-third. Seven airlines based in emerging markets are now global challengers, compared with none 10 years ago.

Pharmaceutical companies based in EMs have also grown rapidly, from $8 billion in revenues in 2005 to $80 billion in 2014. This growth reflects both inroads in mature markets and rising health care spending in emerging markets. Lupin Pharmaceuticals and Sun Pharmaceuticals, both of India, have completed acquisitions to round out their product portfolios. Indian companies now have a 20% global market share for generic drugs and own 22% of pharmaceutical plants approved by the US Food and Drug Administration.

Few global media companies have launched from emerging markets, although that may be starting to change. China’s Alibaba has investments in several online media properties, and Dalian Wanda is buying a majority stake in Legendary Entertainment, a Hollywood studio.

And this is all above the core role EMs keep playing in production of raw materials and infrastructure in the world, as well as meeting needs of the rapidly growing middle class in their home markets and abroad.

BREAKDOWN BY SECTOR

Building and Supplying the World

EMs continue to play a significant role in supplying the world’s raw materials and meeting the infrastructure needs of both emerging and mature economies. That role is in flux, however, and most of the new challengers in this category are emphasizing integration, value-added services, and other higher-end capabilities. The name of the game is no longer simply low cost.

Brazil’s Braskem is the largest producer of thermoplastic resins in the Americas. The company manufactures polypropylene, polyethylene, PVC, and basic petrochemicals. It has grown both organically and through acquisition. Braskem entered the global market with the acquisition of Sunoco Chemical in 2010 and Dow’s polypropylene business in 2011.

The main businesses of the Philippines’ DMCI Holdings conglomerate are power generation, property development, construction, mining, and water distribution. The growing economy and population of the Philippines are increasing demand for energy, infrastructure, water, and real estate. Despite softening nickel and coal prices, operational efficiency has helped DMCI Holdings’ mining business continue to generate value.

Grupo México is the fourth largest copper producer in the world and operates the largest rail network in Mexico. Grupo México benefits from a low cost structure, geographical diversification, fully integrated operations, and strong finances.

The fertilizer company OCP of Morocco has exclusive access to the largest phosphate-rock reserves in the world. OCP has focused on integration, ranging from mining to the production of fertilizers and other value-added products, while reducing its environmental footprint. It has production and distribution joint ventures in Asia, Europe, and Brazil, one of the fastest-growing fertilizer markets in the world, where OCP has created an innovative supply channel. The company is also pursuing growth in Africa by encouraging the development of agriculture and the smart use of fertilizer.

Capturing Middle-Class Consumers

Many EMs are relatively young countries with a rapidly expanding middle class. This generation of consumers is optimistic, with the disposable income required to spend on goods and services. Eight of the new challengers are serving the needs of these consumers, although only three of them are traditional fast-moving-consumer-goods companies.

Peru’s Alicorp has three main business lines: food, personal, and home care products; industrial food products, such as flour and food oil; and animal nutrition. Its consumer brands are well known throughout Latin America.

The Philippine’s conglomerate Ayala, founded more than 180 years ago, has holdings in real estate, financial services, telecommunications, water infrastructure, electronics manufacturing, automotive dealerships, and business process outsourcing. It is moving into power generation, transport infrastructure, and education and is expanding primarily in Southeast Asia.

Started as a largely domestic carrier in 1998, China Eastern Airlines has been rapidly expanding overseas. With its main hub in Shanghai, the airline now flies to several destinations in the US and Europe. It also offers flights throughout Southeast Asia that appeal to Chinese tourists.

The Chinese conglomerate Dalian Wanda has achieved a trifecta. It is the largest owner of luxury hotels, the largest commercial property developer, and the largest owner of cinema chains in the world. It recently announced a deal to buy a majority of Legendary Entertainment, becoming the first Chinese company to own a Hollywood studio. By 2020, Dalian Wanda expects to be one of the world’s five largest companies devoted to entertainment and cultural activities.

South African insurer Discovery has created partnerships and joint ventures with other insurers to enter China, the US, Singapore, Australia, and Europe. Its Vitality health insurance program rewards consumers who make healthy changes in lifestyle. Vitality is currently available in China, South Africa, the UK, and the US.

The consumer goods conglomerate Gloria of Peru is training its sights on regional expansion throughout Latin America. Gloria has an active presence in Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador, Argentina, and Puerto Rico. In 2014, it acquired five companies in Colombia, establishing itself as an important player in that country’s dairy and food and beverage categories.

The largest low-cost carrier in Turkey, Pegasus Airlines increased revenues by 13% and earnings before taxes by 34% in 2015. The company has a 28%-share of the domestic market and a 10%-share of international flights. It is growing twice as fast as the market for international routes.

Universal Robina is one of the largest food and beverage companies in the Philippines, with a growing presence throughout Southeast Asia and beyond. In 2014, Universal Robina bought Griffin’s Foods, the largest snack maker in New Zealand. Last year, the company was named the best-managed consumer company in Asia by FinanceAsia and Euromoney.

Meeting Digital Needs

The three companies below are tapping into the insatiable demand of consumers to be connected at all times.

This mobile operator Axiata of Malaysia has about 290 million customers in 10 Asian countries. It recently bought a controlling stake in Nepal’s NCell. While most mobile operators based in emerging markets have struggled to maintain their profitability in recent years, Axiata’s margin has averaged 38% in the three years ending in 2015.

Indian IT and business-process-services company Tech Mahindra is active in many industries but especially telecommunications, which accounts for one-half of its revenues. Tech Mahindra is the only Indian IT services company with a major presence in the $43 billion network-infrastructure business. It has engaged in several key strategic deals and partnerships in order to expand into new businesses.

Founded in 2010, China’s Xiaomi is already the fourth-largest handset maker globally. It sells more phones in China than Apple and is rapidly expanding into other emerging markets, such as India and Indonesia. It sells directly to customers through online channels and keeps close track of feedback and suggestions through social media.

Paving Path to Global Leadership

As their name suggests, the global challengers have unfinished business to complete. They are on a path to become top companies in their industry, but there is no guarantee that they will get there. On the other hand, companies that we call ‘graduates’ have reached that peak. These 19 former global challengers are virtually indistinguishable from multinationals. What separates those companies from the challengers?

In seeking to understand the difference between challengers and graduates, five ‘under the hood’ attributes were uncovered that separate global leaders from the pack. Collectively, they constitute a winning combination that is greater than the sum of its parts. Indeed, all of the 19 graduates have acquired at least four of these five attributes.

Vision and Culture. In the case of all 19 graduates, their vision is easy to describe and see in action. For example, América Móvil aspires to be the fastest-growing telecommunications company in the world, while Tata Motors’ ambition is to be the car company most admired by customers, employees, and shareholders. Johnson Electric aims to be the most innovative and reliable supplier of motors and motion systems. Many former global challengers also articulated a compelling vision. But they failed to create a culture that unified the company and amplified individual effort and achievement.

Operating Model. The operating models of global leaders are built to go global and to be adaptive. They are not modified versions of the model designed for the company’s home market. Global leaders build global processes, especially for risk management and other core activities, but are willing to bend the rules so that local markets can make adaptations. Hindalco, for example, has deliberately created a portfolio of high- and low-margin products in order to provide a buffer against ups and downs in the economy.

Talent and Organization. Talent and larger organizational issues are often what distinguish global leaders, since the demand for great people is so intense, especially in EMs. Global leaders build global leadership and talent programs, rotate top people through geographies, and create opportunities for star talent outside of the home market. They build an employer-of-choice brand in key recruiting markets. They know how to integrate talent and retain key aspects of their culture when they acquire other companies. They create cost-effective training engines for line workers and middle managers. Tata Consultancy Services, for example, has learned how to scale its recruiting, onboarding, and training engines for the 50,000 or more employees that join the company each year. Such companies as Lenovo and Emirates Airlines have created a diverse and international workforce at all levels.

Go-to-Market Model. Global leaders understand how to be successful in many markets. They make smart local acquisitions and develop local partnerships to fill in the gaps in their coverage, product portfolio, or distribution networks. Meat processer JBS, for example, has created strategic partnerships in key geographies, established direct-sales teams, and located production facilities in low-cost countries.

Innovation and Reinvention. Global leaders are continually innovating and, when necessary, reinventing themselves to stay relevant. Li & Fung will create and shutter business units as necessary. Recognizing that beer tastes are regional, SABMiller uses local ingredients in its breweries. In Africa, for example, it offers many bottle and can sizes and uses local crops like sorghum to brew affordable beer.

To better understand these factors, two pairs of companies in two industries were examined. They started in similar positions of strength, but their fortunes took dramatically different turns. In one case, a large industrial goods conglomerate took advantage of a favorable cost structure, strategic M&A, and strong leadership to rise to the top of its sector. Managers knew how to execute and how to work with local partners in new markets. The other company focused on achieving efficiency and reaching production targets, but management conflicts and low-performing assets kept it from continuing on its growth path. The first company is now a global leader. The second has fallen off the global challenger list.

The companies in the second pair are both involved in similar technology, media, and telecom businesses. One invested heavily in innovation, especially localized R&D. It actively developed new technologies, both in-house and in partnership with outsiders. It developed modern, agile ways of working. The other company remained true to its command-and-control bureaucratic structure, which led to sluggish decision-making and a lack of local adaptation. Its innovation strategy was reactive, responding to requests from customers, rather than forward-looking. Not surprisingly, the paths of these two companies also diverged – global leadership for one, falling revenues for the other.

Graduating

companies: basic

strategic approaches

While graduate companies share most of the five attributes described above, they did not all achieve success and competitive advantage in the same way. Their three primary strategic approaches were identified, as they:

…rely on strategic M&A and world-class integration to create long-term value. Mexico’s Cemex in cement, South Arica’s SABMiller in beer, and Mexico’s Alfa have successfully integrated companies with diverse cultures and spread best practices.

…scale and replicate a successful business model to achieve growth. Li & Fung, headquartered in Hong Kong, has become the largest global supplier of clothes and consumer goods by acting as supply chain manager between consumers and manufacturers in Asia and elsewhere. Wilmar International, headquartered in Singapore but with major holdings in Indonesia, has become the world’s leading supplier of palm oil by developing an integrated origination-to-distribution business model. Both companies had a singular vision of what they needed to do to go global and achieved it.

…emphasize innovation and global branding. UAE’s Emirates Airlines has become a world-class airline by providing a superior passenger experience. Likewise, China’s Lenovo has maintained a heritage of quality and innovative design in the PC business, which it acquired more than a decade ago. And unlike other telecom suppliers that have focused on low cost, Huawei has invested in R&D and innovation in order to provide high-quality products. These companies have demonstrated an ability to both develop global brands and be relevant in local markets.

New Champions: Challenging the Challengers

The abovementioned plagues and risks of the global economy do not need to be showstoppers for the global challengers and other aspiring companies in EMs. Most of these markets are still growing faster, and their demographic and consumer spending trends are more favorable than their mature counterparts.

Between 2015 and 2030, for example, the population of EMs is set to expand by 17%, more than three times faster than the rate in mature markets. The urban population of sub-Saharan Africa will rise by 70%, double the still impressive rate of the Asia-Pacific region, and more than three times the rate of Latin America. And, even if GDP growth slows to 5.5%, China and India will add $3.9 trillion in consumption over the next five years, equal to the entire GDP of Germany. EMs will account for one-third of global consumption by 2020, up from 29% in 2015.

It’s a more challenging environment than it was five years ago. But for companies that want to send themselves into global orbit, emerging markets are still strong launching pads, albeit ones that are becoming more crowded.

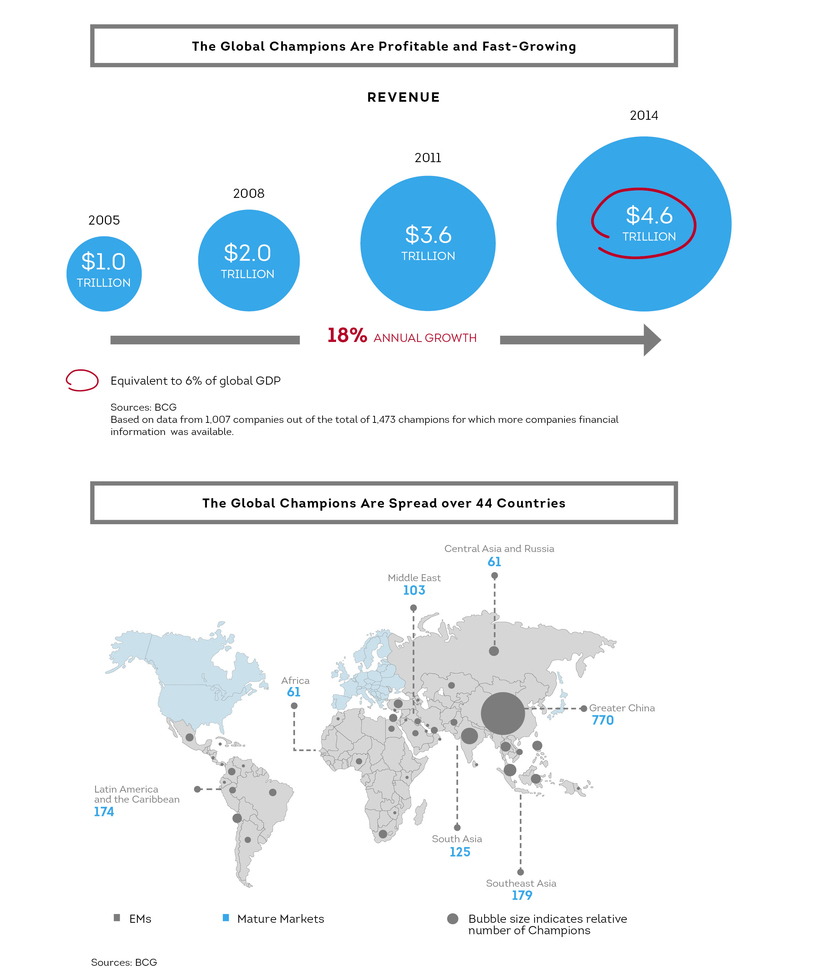

As global challengers look to grow in a slower-growth world, however, they will face increasing competition not just from multinationals – their historic adversaries – but also from homegrown rivals. Nearly 1,500 companies based in EMs can be identified that, while not qualifying as global challengers, are still successful, growing companies. These companies – the champions – tend to be smaller than the challengers but still highly profitable and fast-growing. Indeed, from 2005 through 2014, they averaged 18% annual growth and in 2014 had revenues equivalent to six percent of global GDP. While many of them have regional or global ambitions, others are wholly focused on their home market.

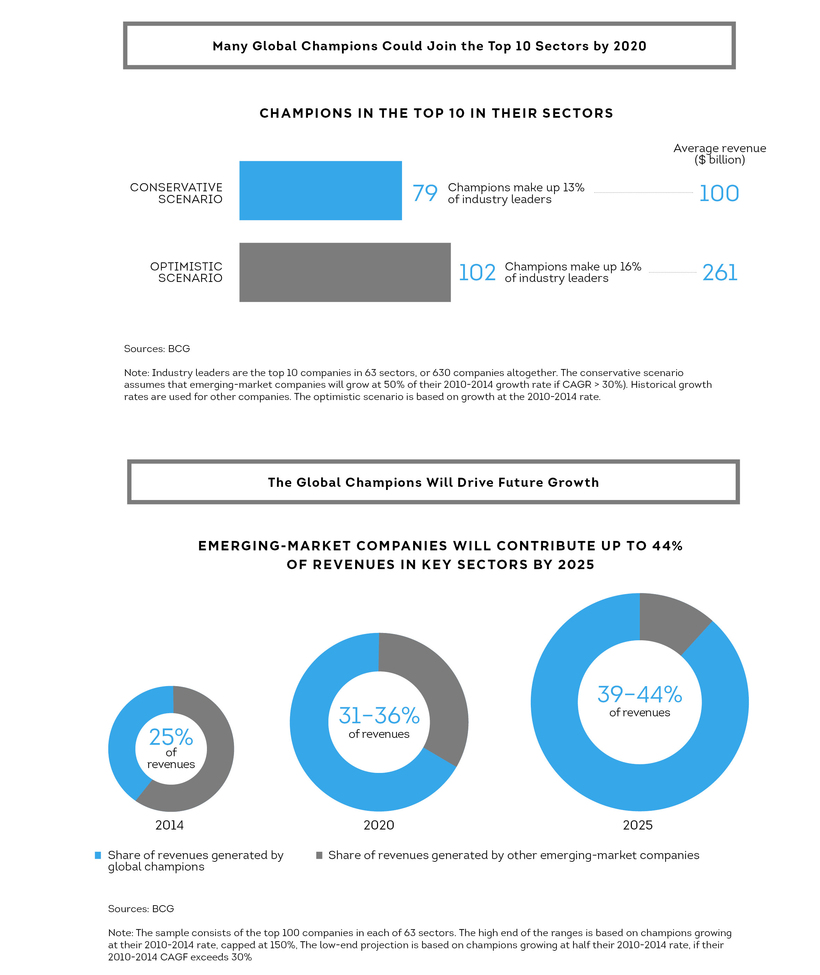

Champions are companies to watch over the next 10 years. Like the global challengers, they are concentrated in China and India. But African, Latin American, and Southeast Asian companies are also well represented. The champions have grown faster than the global challengers over the past five years and are more profitable. Given their current growth rates, many champions are likely to become top-10 companies in their industrial sector by 2020. These companies will also be responsible for most of the world’s economic growth through 2025. In other words, within five years, the top-10 lists of many industrial sectors will be populated by several companies that are virtually unknown today outside their home market.

To be sure, the road ahead will be more challenging than the one just traveled. Despite the growing middle class and increasing disposable income in many of these markets, global challengers and champions alike are not immune to macroeconomic forces. They cannot necessarily count on the purchasing power of mature markets to fuel growth or on foreign investors to fund their capital needs. More than $500 billion of net capital flew out of emerging markets in 2015. Commodity players cannot depend on China’s once insatiable appetite for raw materials. They will need to do more than float higher on the tide of an expanding economy. They will need to compete.

Still, we are bullish on the long-term growth of many of these markets and even more so on the homegrown companies they have produced. Global challengers know how to win in volatile and uncertain times.

These companies are still developing world-class capabilities, although here increasingly they will need to rely on strategic M&A to build their capabilities and reach their goals. Not all of them will be up to these tasks. But if their past is any indication, most of them will continue to be viable companies, and many will become global leaders.

And unlike 10 years ago, when their

primary competitors were multinationals, global challengers today face a

new generation of local competitors. Finally, both the challengers and

their homegrown competitors are vying for a pool of local revenues that

is expanding less quickly, forcing them to seek growth elsewhere. Given

these headwinds, global challengers – and companies that aspire to that

status – must focus equally on growth and competitiveness. We still

expect the overwhelming majority of them to thrive in this new world

order. They are proven winners.

This is an adapted version of the Global Leaders, Challengers, and Champions: The Engines of Emerging Markets report by BCG released in June 2016. BCG published its first list of global challengers 10 years ago to highlight the achievements of companies that were ‘changing the world.’ In this, the 10th anniversary of that inaugural list, BCG looks more broadly at emerging markets and the dynamic companies, encompassing nearly 1,500 firms, they produce.

The BCG team of contributors to the report includes Daniel Azevedo, Vincent Chin, Dinesh Khanna, Eduardo León, Kasey Maggard, Michael Meyer, David C. Michael, Burak Tansan, Peter Ullrich, Sharad Verma, and Jeff Walters.