Hindustan, the Faraway Island

Evgeny Pakhomov

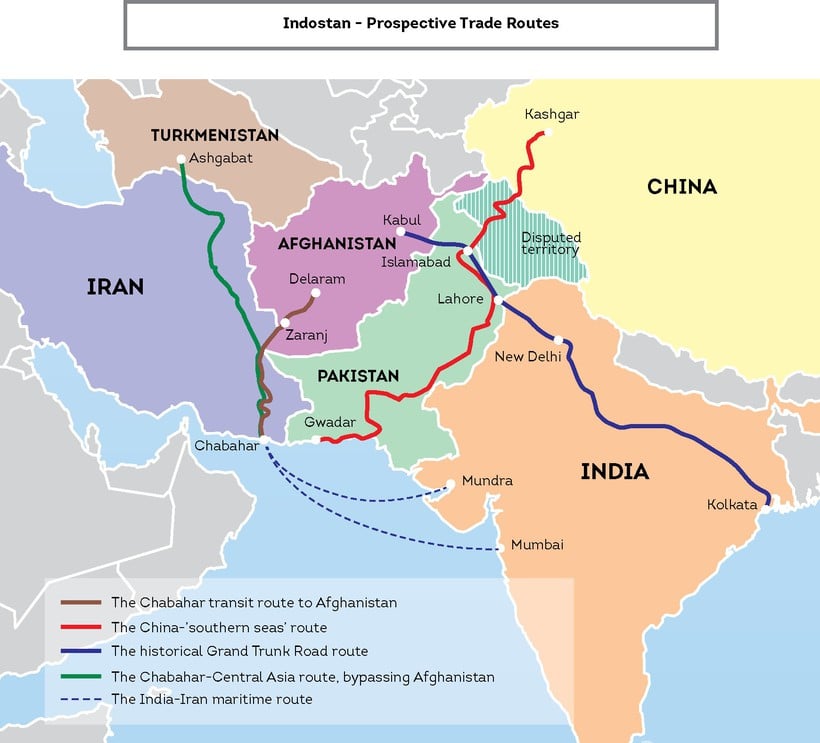

A new front is about to flare up in the war for control of trade routes between Asia and Europe. India and Pakistan – the two largest countries on the Indian subcontinent – are determined to break out of their geographical borders and link themselves to the European continent through new transport routes.

Geographically, the Indian subcontinent is both lucky and unlucky. It is fenced off from the rest of the world – in the north by the Himalayas, the tallest mountains in the world, in the northwest by a desert, and in all other areas, by the Indian Ocean. Precisely because of this ‘natural isolation,’ India has developed independently for many centuries. On the one hand, this has allowed it to maintain its originality and its unique natural resources. On the other hand, this has always presented a major obstacle for trading exceptional Indian goods – spices, cotton, silk and cashmere fabrics, incense, rough and polished diamonds, ambrosia and musk – in European markets.

Numerous attempts to establish direct trade corridors between Hindustan and the West have failed. The first to try and solve this problem were the British, who built a railroad from British India to the border of Afghanistan through the Khyber Pass at the turn of the last century by blasting about 40 tunnels through the mountains. The project was met with fierce resistance from Afghan tribes; the remains of those rusting rail tracks are still found on the slopes of the Spin Ghar.

Today, the problems have only multiplied. Modern India is often compared with a vessel sealed with two corks – Afghanistan, with its perpetual instability, and Pakistan, which does not allow the use of transit routes through its territory since it considers New Delhi to be its main military opponent. Endless negotiations meant to try and normalize relations between the two fragments of British India, which split along religious lines in 1947, have yet to bear any tangible results. The situation is further complicated by territorial disputes, especially over Kashmir, a situation that both countries are unhappy about.

Modi and Chabahar

India, which is getting ready to become one of the world’s superpowers and main industrial centers by the middle of this century, is particularly dissatisfied. Last year, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi announced the launch of a new industrialization program under the ‘Make in India’ slogan with a view to growing exports. In this regard, New Delhi urgently needs new export routes.

Today, only one party may consider itself the winner in this South Asian transit race – China. In contrast to India and Pakistan, it does not feel such an urgent need to open a Trans-Afghanistan route, and it has mostly achieved access to the ‘southern seas’

Iran is also ready to offer help. India has agreed with Tehran that Indian goods should go by sea to the Iranian port of Chabahar on the Gulf of Oman (located very close to the new Pakistani port of Gwadar). From there, loads labeled ‘Made in India’ will be sent to Afghanistan, which is a stone’s throw from Central Asia. The contract, signed last year, also says that India should carry out a comprehensive modernization of Chabahar’s infrastructure. New Delhi is allocating about $100 million for this purpose, while the noticeable improvement of relations between Tehran and the West should help move the project along. “Iran is under international sanctions and Washington has opposed any development of economic relations with that country for many years,” said Sergei Kamenev, head of the Pakistan department of the Institute of Oriental Studies, in an interview with BRICS Business Magazine. “A marked warming of relations between Tehran and the West, emerging in recent years, may have a positive impact on the Chabahar project.”

Chabahar is the first foreign port development in cooperation with India, which in itself testifies to the great importance given to the project in New Delhi. India can use the port to send goods to Afghanistan and to Central Asia bypassing the Afghan territory.

This is why India is sponsoring the repair and construction of a highway stretching some 200 kilometers through Afghanistan, which would be used by trucks from Chabahar. On top of that, it should give New Delhi an additional trump card in the political rivalry with their nearest neighbor and competitor. “The Chabahar project obviously has another goal – to put pressure on Pakistan and force it to be more compliant,” said Omar Nessar, Director of the Center for Modern Afghanistan Studies in an interview with BRICS Business Magazine. “Islamabad has yet to allow Afghan trucks through to India, so one of the oldest routes in Asia is not yet fully operational. But if the project of transiting Indian goods through Chabahar is finally realized, the value of the Pakistani route will drop sharply. And Pakistan must understand that.”

But apart from Pakistani politicians, there are others who resist the idea of trucks from other countries passing through Pakistan – the infamous ‘road mafia,’ a strictly structured community of local long-haul truck drivers, well known for their richly decorated trucks. They control cargo transportation in the northwest of the Indian subcontinent and are not ready to give up their monopoly, effectively lobbying their own interests in the government.

Despite this, India and Afghanistan seem to harbor hope that the legendary route from Kabul to the Indian subcontinent (the ‘Grand Trunk Road’ celebrated by Rudyard Kipling), will return to its former glory. It is no coincidence that as recently as this year, the new president of Afghanistan, Ashraf Ghani, and India’s Prime Minister Modi urged Islamabad to open the Vaga crossing point on the border with India for Afghan trucks and Indian goods. Of course, any response to this appeal remains to be seen.

Trucks and the Taliban

However, the life of Pakistani truck drivers is also not enviable – the roads of ever-warring Afghanistan are always full of unpleasant surprises. Curiously, even the history of the Taliban, which is now included in the United Nation’s official list of terrorist organizations, began with a fight for control of these trade routes. In the mid-1990s, the government of Benazir Bhutto in Pakistan decided to liven up the national economy by developing trade with the new states of Central Asia. Islamabad wanted to fill those new countries with its consumer goods. In October 1994, a convoy of 30 trucks (offered by the same ‘road mafia’), full to the brim with a variety of goods, set off from Afghanistan to Ashgabat with great fanfare. Yet, they did not get very far. At the Afghan city of Kandahar, a squad of men under local commander Mansur Achakzai plundered the ‘caravan of friendship,’ took the drivers hostage, and demanded a ransom from Islamabad. It was then that the former head of Pakistan’s Interior Ministry, Nasrullah Babar, suggested that the ruling cabinet seek help from young but militant students of religious schools who called themselves ‘the Talibs’ or ‘students.’ The latter eagerly responded to the authorities’ request. They attacked and surrounded the Mujahideen, recaptured the trucks, and then brutally executed the leader of the Mujahideen group. The story goes that the ‘students’ hung Achakzai’s body on the barrel of a tank cannon and drove it to the nearest town for everyone to see that robbing trucks from Pakistan was a big ‘no-no.’

Apart from Pakistani politicians, there are others who resist the idea of trucks from other countries passing through Pakistan – the infamous ‘road mafia,’ a strictly structured community of local long-haul truck drivers, well known for their lavishly adorned vehicles

It was after that incident that Islamabad agreed to officially recognize the Taliban and provided them political and military assistance. It was crucial for Pakistani authorities to ensure safe transit through Afghan territory. Support for the Taliban has also had an impact on present relations between Kabul and Islamabad. The new Afghan government and Pakistan have for years been trading accusations about the lack of fervor fighting against heavily armed ‘students’ who actually threaten the current government.

But in spite of all their differences, the parties managed to agree on the transport routes, since the potential benefits made it easier to meet each other half way. In 2010, Pakistan and Afghanistan signed a bilateral agreement on transit (APTTA), which gave Kabul the chance to export goods to India. At the same time, Islamabad confirmed an agreement signed in 1950, which allowed Afghanistan the use of Pakistan’s largest port of Karachi for the handling of their cargo.

Pakistan intends to use the very same sea gates for the supply of oil from Kuwait by Tajikistan – the corresponding preliminary agreement was reached by Islamabad and Dushanbe late last year. The initial agreement involves handling 100,000 tons of crude oil, which must be processed at Pakistani refineries. The resulting petroleum products are to be sent to Tajikistan. In the future, the volume of oil exports from Kuwait could increase to 1-2 million tons per year. If this project is implemented in full, the Kuwaiti hydrocarbons could displace Russian oil from the Tajik market.

At the beginning of this year, Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Tajikistan declared their readiness to sign a tripartite agreement on transit in the coming months. This could signal the realization of Islamabad’s old dream; the contract could open a gateway for Pakistani goods to Tajikistan and further to Central Asia. Tajikistan, on the other hand, will also gain access to Pakistani seaports via Afghanistan. Kabul, in turn, intends to charge for transit, and, in the future, use the route to export its own goods – especially iron and copper ores, the quick production of which the local authorities are counting on.

The Second Front

The unspoken competition between India and Pakistan for the expansion of its transportation routes may be interrupted by other, very influential forces. For instance, Islamabad may receive help from one of its old and tested allies – Beijing. While building its own trade strategy, China has long viewed Pakistan as an important transit country for its product supplies to the Middle East, Africa, and further to the West. The cooperation between the two countries in this area has a long history. Back in the 1960s and 1970s, Islamabad and Beijing built the highest paved international highway in the world – the Karakoram Highway, which runs through the Khunjerab Pass, known since the days of the Great Silk Road, at an altitude of 4,700 meters. The highway is shut down in the winter, but in the summer it is covered in caravans of trucks from the Chinese Sinkiang Uighur to the Pakistani city of Rawalpindi.

Today, the military significance of the road has become inferior to its economic importance. On the basis of the Karakorum Highway, Beijing plans to create an entire transport network from the port of Gwadar on the coast of the Gulf of Oman, using it to connect its western regions to the sea.

The use of Gwadar, built by Chinese companies in five years, began in 2007. But according to the current project plans, in the long term it will be connected through the mountains to the ports of Guangzhou and Fangchenggang in China. Its main goal is to facilitate access of Chinese goods to the Middle East and Africa. Beijing also gains access to the ‘world’s kerosene shop’ – the Persian Gulf.

Furthermore, the development program of the Pakistan-China transport corridor involves the construction of pipelines and even a railroad through the high-mountain Khunjerab Pass. According to the plan, the route should go through a territory disputed with India, but this does not seem to worry China at all. The project is part of a strategic plan to build the Silk Road Economic Belt first announced by Beijing in 2013, aiming to create a new ambitious trade and transport corridor between Asia and Europe.

However, it is possible that a new front in this ‘transport war’ might be opened by another influential force – the United States. Back in 2011, Washington announced its own idea of a new ‘silk road.’ Its main objective was the development of trade relations between the countries of Central and South Asia, including through the expansion of transport and energy networks.

A fact not to be ignored is that the importance of the routes in the region is well known to the U.S. from experience. One of them was used to supply NATO troops in Afghanistan; NATO logistics support went from the West to the Pakistani ports on the Arabian Sea primarily through Karachi. From there, those same brightly adorned Pakistani trucks carried fuel, medicine, spare parts, and other goods for NATO forces through the Khyber Pass into Afghanistan. Moreover, the US has built or repaired more than 3,000 kilometers of roads in Afghanistan over the past few years. Washington backed the Pakistani-Afghan Transit Trade Agreement (PATTA) and expressed willingness to assist in the modernization of the network of customs entry points to simplify customs transit.

The Stumbling Block

Whatever the case may be, the success of the vast majority, if not all, of these projects depends on whether the main obstacle – the very unpredictable Afghanistan – will be removed. “If transport corridors through Afghanistan were to open, it would contribute to strengthening the country’s stability. However, these routes will not work until the country is stable,” said Omar Nessar. “So for now, all parties involved in these projects are in no hurry to begin full-scale transit, and are waiting to see what the situation will be like in Afghanistan.”

In the meantime, only one party may consider itself the winner in this South Asian transit race – China. In contrast to India and Pakistan, the People’s Republic does not feel such an urgent need to open a Trans-Afghanistan route (Chinese goods go to Central Asia directly), and it has mostly achieved access to the ‘southern seas.’

“China is determined to have an outlet to the Arabian Sea via Pakistan. There is no doubt that it will do everything it can to ensure that this route is operational,” said Sergei Kamenev. While the others wait on Afghanistan, Beijing is building roads and ports along a route drawn according to its own maps.