Hipsters and Other Signs of Colombian Recovery

AA Gill

Bogotá’s airport is El Dorado. If you’re nervous about flying, buying a ticket to a mythical place that has already cost thousands of lives, the destruction of empires and civilisations might make you think twice. But then, El Dorado is what people have come here in search of for 600 years. It literally means The Golden One and derives from the most powerful and, it turns out, misguided and pitifully cataclysmic myth of all of Mesoamerica: about a pre-Columbian king snappily called the zipa, who would be covered in gold dust and dive into a lake, glittering like the setting sun. His capital was Muequeta, high in the Andes. The lake is still here, out of town, along with a salt cathedral.

But first there’s the traffic. Bogotá suffers Gordian traffic jams, made bearable by the novel and quite flamboyant cirque de traffic lights. As you stop, a man on a unicycle unsteadily pedals out. He juggles unsuccessfully, while a chubby girl with a comedy hat and clown’s make-up does callisthenic dancing with silk streamers like a one-woman North Korean dictator’s birthday celebration, and another child will tap on your window for change.

One of the consequences of years of terrorism and drug gangs meant that anyone who was a kidnap risk, and who could afford to, left Colombia. The diaspora went to America and Europe and a generation of children grew up cosmopolitan and educated abroad. Now they are returning and property prices in the most exclusive areas are as expensive as New York or Paris. The expats have brought back money and culture and avariciousness for smart shopping centres and chic atelier galleries selling contemporary art at international prices

This is part of a general drive to lift the city, give everyone a role and bring culture to the street. Drivers grin and mostly offer a few coins. It’s the most inventive traffic calmer I’ve seen in any city. Bogotá has decided that everyone and everything must have culture and self-expression: it’s mission art growing from the cracks in the pavement. Barely five years ago, the only people who’d visit this place with a sense of expectation or excitement were drug mules or kidnap negotiators. Bogotá had a hard-fought reputation for being one of the most dangerous cities in the world. Colombia was known only for drugs and terrorism, the Siamese twins of misery, the world’s biggest cocaine producer and the world’s most consistently intractable old-school communist revolutionaries with the best terrorist name, the Farc.

When drugs met Trotskyist dogma there was a perfect storm of nihilism. But then something happened that wasn’t politics or common sense or revolution. No one knows quite what it was, but a sense of exhaustion with the misery set in and the Farc announced a unilateral ceasefire, and the government is about to make a serious peace offer. Politics have become softer, more malleable, and at the same time the drugs seem to have gone limp and legit.

A conflict negotiator (a job description that’s as ubiquitous here as hedge-fund manager in London) said the coca is still grown but the business model has changed. A generation ago, drug gangs and gangsters saw themselves as mafia or wanted to be Scarface: it was bling and hookers and drive-by Uzis, and headless bodies left in ornamental fish ponds as a warning. Pablo Escobar ended up as a bullet cushion on the roof of a favela in Medellín.

But today the drug lords have been to Harvard Business School and they see themselves not as dealers but brokers, and the business model isn’t Al Pacino but Amazon, which is appropriate because they actually do have the Amazon. The fratricidal violence in Mexico today, they say with a knowing shrug, is what Colombia had a decade ago. So passé. Now that Colombia’s carcinogenic problems are in remission, we can look at what else it has, and that comes with a shock.

This is the most bio-diverse country in the world. It has a bewildering number of habitats: the mountains, the rainforests, pampas, wetlands, a great network of rivers, including the Amazon, two coasts – the Caribbean and the Pacific – and it has more species of birds than all of Europe and North America put together. A phenomenal number of things grow here. This is some of the finest, fecund farmland on the globe. Some say if a man with a wooden leg stands still for too long, he’ll turn into a guava tree.

The Paloquemao market in the city is a jaw-dropping carnival of fruitarian wonder to anyone who’s remotely interested in the riches that really do grow on trees. The sad, ghostly taste of our imported fruit is, here, transformed into a steepling cornucopia of astonishingly beautiful things. Half a dozen varieties of banana and plantains and mangoes; limes, lemons, oranges, guavas, carambolas, kiwis, strawberries, dragonfruit, mangosteen, all the rare and exotic fruits of the east, and then the wonders of the rainforest: knobbly, finned and flared, bright and dowdy fruit, guyabano – which tastes a bit like a banana and a bit like a strawberry, but then again, a bit like a lime – lulo, nispero, tree tomato, sapote, curubu, sugar apple, guaba.

The smell that wafts through the narrow alleys of stalls is the scent of fairy tales, heady and brilliant, the bounty of Eden. There’s meat, as well: any number of indigenous and effortful things to do with a pig, including a huddle of pigs’ heads attached to neatly flayed skins, like lifelike glove puppets, or rugs of crackling. I stop at a little wooden shack in the heart of the market. Inside it, a fat chef manhandles the ladle through a thick, simmering cauldron. It smells so good, I sit down beside them and point at the bowl and then at my mouth, and smile. The market also deals in cut flowers, huge bundles of arum lilies, bunches of tulips, roses and orchids and strange wreaths of ruddy fleshy, erotically promising rainforest blooms.

The two quickest guides to the nature and wellbeing of any city are its markets and its graffiti. Graffiti is a feature of Bogotá, encouraged by the municipality. The central motorway that bisects the town is a long gallery of political manga, paintings commemorating the dead and exalting political change, extolling healthy diets, making jokes, offering dystopian visions and caricatures and belly laughs. There are huge political murals and tiny stencilled graphic bons mots. The street art is itself a reason for visiting the city: an inside-out gallery of contemporary thought and social commentary, energetic, angry, licensed but not tamed. Given the space and the freedom, you see it as a beautiful addition to the practical infrastructure that is so often a sign of urban decay and neglect. Here it is rejuvenation, energy, commitment and joie de vivre.

Above Bogotá there is a church on a mountain that makes you lurch for breath it’s so high. You reach it by funicular and the view of the city from above is spectacular: 8 million people, palely confused like a split sack of mosaic tesserae, stretching away. There are bits that have kept their colonial elegance and some places that look weirdly like commuter-belt Esher, built in an English Tudorbethan vernacular. There are parts that have a licence to run speakeasies and brothels, and others where it is probably not safe to wander round looking rich or gormless.

One of the consequences of years of terrorism and drug gangs meant that anyone who was a kidnap risk, and who could afford to, left Colombia. The diaspora went to America and Europe and a generation of children grew up cosmopolitan and educated abroad. Now they are returning and property prices in the most exclusive areas are as expensive as New York or Paris. The expats have brought back money and culture and avariciousness for smart shopping centres and chic atelier galleries selling contemporary art at international prices. I walked around one with a gentle, young curator who spoke the fluent international art bollocks you hear in any western city that has a Frieze or a Biennale.

Graffiti is a feature of Bogotá, encouraged by the municipality. The central motorway that bisects the town is a long gallery of political manga, paintings commemorating the dead and exalting political change, extolling healthy diets, making jokes, offering dystopian visions and caricatures and belly laughs. There are huge political murals and tiny stencilled graphic bons mots

Bogotá has managed to grow the delicate proof of a healthy social ecosystem: indigenous hipsters with beards, short trousers, fixie bikes and an obsession with coffee. Bringing barista OCD to Colombia is coals to Newcastle because they already have the most delicious coffee, but now you can talk about it for five minutes to a hirsute waiter with ironic tattoos.

Bogotá has managed to grow the delicate proof of a healthy social ecosystem: indigenous hipsters with beards, short trousers, fixie bikes and an obsession with coffee. Bringing barista OCD to Colombia is coals to Newcastle because they already have the most delicious coffee, but now you can talk about it for five minutes to a hirsute waiter with ironic tattoos.

Along with the return of middle-class Colombians, there is also the desperate influx of refugees. Colombia has the highest number of internally displaced people in the world. On the street corner, I stop to chat to four Michael Jacksons in full costume with a boom box. They take it in turns to moonwalk and jive in front of traffic at the lights. They’re very good at it, they make it look fun, but it’s tough.

Hotels are the bellwethers of a city’s state of mind. Are they large concrete boxes with speed humps, guards with mirrors on sticks and lobbies full of UN aid executives, television crews and security advisers? Or are they bijou, low-lit, open-plan hostelries with chillaxing bars in the lobby and smiley girls in black frocks who make you think they’ve gone to a shop and said, “Yes, this fits me perfectly, do you have it in a smaller size?”

Bogotá is attracting the latter. There have been trendy new openings of the W and the deeply unfortunately baptised BOG Hotel, which are proof that it’s safe to dive into the city again. The bedrooms have suggestive buttock cushions and the minibars are stocked with condoms. They’re opulent, suggestible and effortfully sophisticated, but more importantly, they are not just wishful thinking. Someone has taken a long accountant’s look at Bogotá and said: “This is open for legitimate business, and après business shenanigans.”

In a square in the middle of the city, groups of old men stand talking in the slowly loquacious manner of chaps who have nowhere else to be. They’re all dressed beautifully – nicely cut Sunday suits with flashy accents: a broad lapel, a jazzy check, a bit of a watch chain, two-tone shark-skin shoes, a straw fedora. They’re tough men. Short, like most Colombians, with stubby hard hands. If you hang around long enough one of them will saunter over and produce a small wrap of paper from a pocket and open it. They’re not drug dealers, they’re emerald miners, probably emerald poachers, and they will show you little intense shards of viridian green precious stone, or beer bottle glass. You decide.

Women like to be noticed. There is a sashaying fashion for prominent derrières. Like the great poop decks of sailing ships, they sway in the crowd, pressed into spinnaker skirts. The bars and restaurants are full of long, repressed flirtations and the daring of hope and plans and commitment. Many chefs and restaurateurs have come home, bringing a renaissance of indigenous cuisine mixed with other Latin American traditions and hyphenated with eastern and European kitchens: Colombian-Japanese, Colombian-Italian, and an awful lot of this season’s food fad, Peruvian. The ingredients are so good that you’d have to be a seriously cack-handed cook to muck up dinner.

Bogotá is a city that feels like it’s letting out a long sigh of relief, that’s remembering old dance steps to half-forgotten tunes. The two most famous Colombians are Botero, the painter of fat people who once looked like naive social commentary and now just look like life paintings. And Gabriel García Márquez, who has a library built in his name. Although he spent most of his life in Mexico, they say he is quintessentially Colombian and the tourist board relentlessly push ‘magical realism’ as a slogan. Driving through a residential neighbourhood I see a man sitting on a child’s swing swaying backwards and forwards, his back slumped, chin on chest, hands gripping the ropes. There is something intensely pitiful in this brief image. Then, when I walk in Bolivar Park, the big open space with its boating lake and cafes, where the city folk come to run and cycle and lie in the grass, reading and kissing, I notice again solitary men rocking on swings like bears in zoos, soothing the trauma with rhythmic movement.

There is, under the resilience and fashion, the eating and shopping, the dressing up, a low, keening melancholy. Everybody here has been affected by the years of strife, the murders, the kidnappings, the disappeared, the collateral damage, the loss. The sense of grief in the thin air adds a depth, a cello note, to the jollity. The thing about magic realism is you never know when the magic will evaporate and leave you with the very real reality.

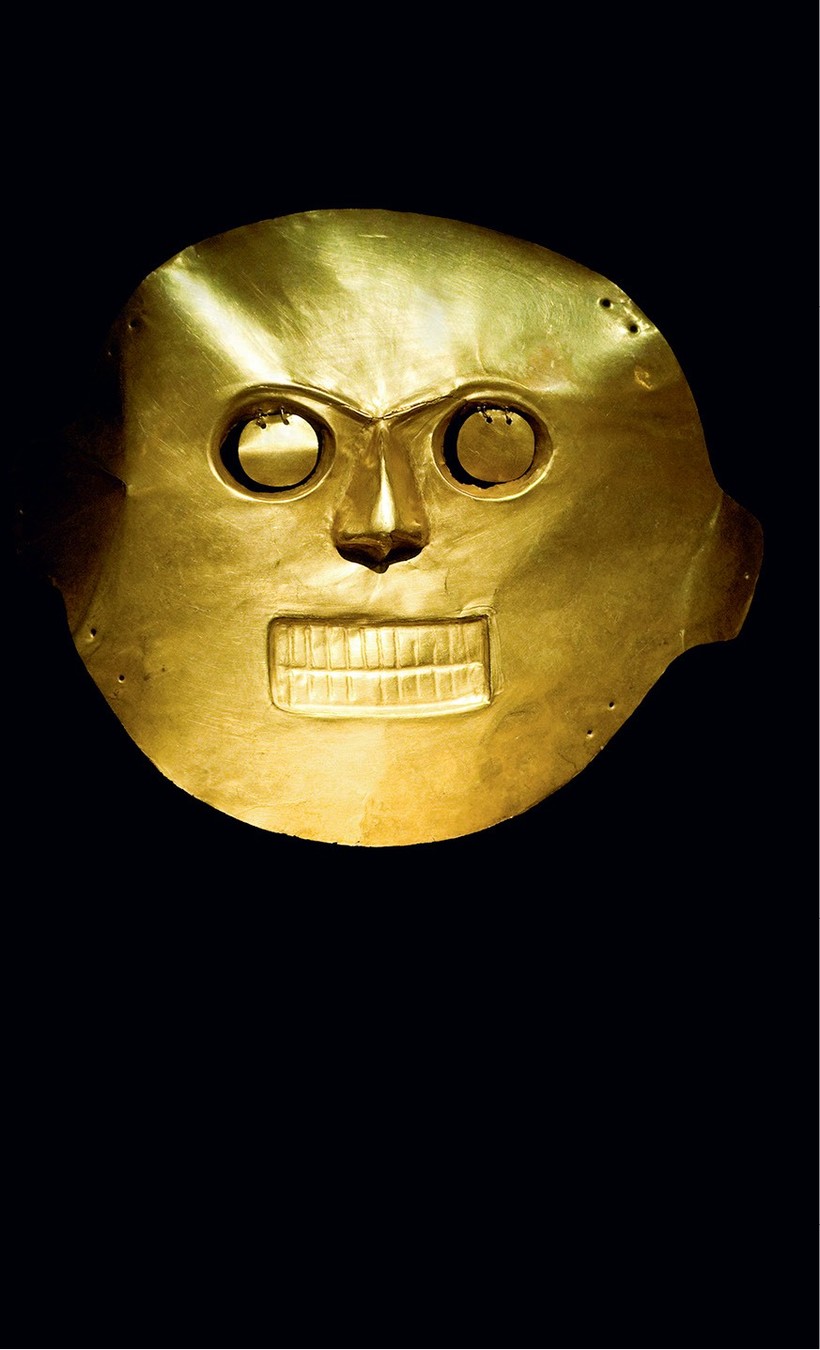

The Gold Museum is Bogotá’s greatest treasure, both in reality and magic. Here’s the work of the pre-Columbian civilisation that made votive and decorative objects out of yellow gold. It is a singularly stunning collection, not least because of what it conjured up and what was lost. How delicate and mercurial the gold seems, so unaware of its terrifying power. Finally, you walk into a dark room. The lights slowly come on, illuminating a panorama of metal that glitters and glints and stares back an accusation and reflection of the riches of the new world, and you feel yourself sinking down and down, through a great magical lake surrounded by the offerings of the future and the drowned prayers of the past.

Four hundred miles away from Bogotá and its tentative renaissance lies Colombia’s Caribbean queen – Cartagena. If the country’s rep for crime and Kalashnikovs kept visitors from the capital and swathes of the countryside in the past, it was the picturesque safe haven of Cartagena that drew them in the first place. Then as now, few visitors to Colombia pass up the opportunity to lose themselves in the fortified old town – a maze of colourful Spanish colonial-era alleyways where vibrant sprays of bougainvillea burst from balconies, imperious baroque churches overshadow sedate plazas and toucans land on your cafe table as often as la cuenta, if you’re lucky.

Colombia has been known only for drugs and terrorism. Today the drug lords have been to Harvard Business School and they see themselves not as dealers but brokers, and the business model isn’t Al Pacino but Amazon, which is appropriate because they actually do have the Amazon

Gabriel García Márquez’s magical realism wells up in these 16th-century streets, but ebbs the moment you step outside their Unesco-protected walls: testament to the city’s touristic pulling powers are the ritzy beaches backed by towering condos to the south of the old town – Bocagrande, Cartagena’s answer to Miami’s South Beach.

The white sands of the nearby Rosario Islands provide a more idyllic getaway. Or half-forgotten backwaters such as Mompox – once Colombia’s third city, now a colonial relic undergoing a mini-renaissance of its own on an island with no bridges in the Magdalena River. For a wide-eyed caffeine kick, make for the coffee fincas around the lush Cocora Valley, 100 miles west of Bogotá.

But it is Colombia’s second city, Medellín – once the world’s murder capital – where Marquezian miracles are taking place: you can even do a walking tour of the city’s notorious Comuna 13 barrio and ride the outdoor escalators and cable cars that provide a lifeline up and down the sides of the valley that is home to 2.4 million people.