Does the Economy Grow in the Woods?

Russia accounts for one fifth of the world’s forests, yet instead of cultivating these resources, the country is subject to deforestation. Russia is the world’s largest exporter of unprocessed timber, but there isn’t a single Russian company among the world’s 100 largest paper mills. It is the only BRICS member that is completely absent from that ranking. Russia is falling short because of a lack of large-scale sustainable forest management practices – but the situation is gradually starting to change.

Forest Ecosystem Challenges

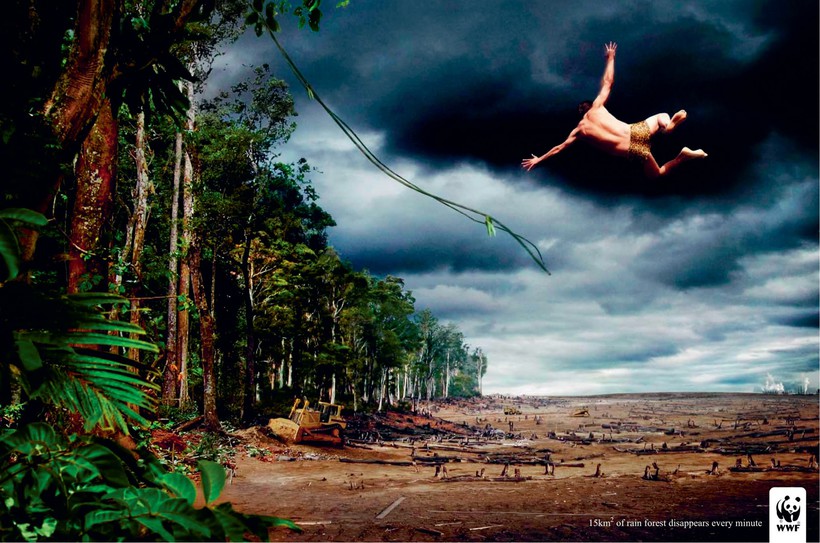

Forests cover nearly 31% of the world’s landmass, according to data presented at September’s World Forestry Congress in Durban. The forestry sector employs around 1.7% of the global workforce. Furthermore, according to the World Wildlife Fund (WWF), forests provide fresh water for two-thirds of the planet’s population and are home to more than two-thirds of its flora and fauna. However, today’s forest management practices are causing irreparable damage.

Firstly, as the human population continues to grow, the demand for forest industry output in several categories is also going up. This causes problems because it requires more and more resources to be produced within an already widespread and extensive model.

Secondly, our cities are growing and our agricultural lands are expanding – two processes that lead directly to the felling of forests and the loss of large, accessible woodland areas.

Accelerated deforestation is also driven by the growing demand for forest industry products. According to the United Nation’s Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE), there are more than 90 core types of exported and imported goods in the timber category alone. At the same time, demand in selected segments has gone up from five percent to 12%.

Finally, deforestation of large areas is not just caused by anthropogenic factors. There are also ever-increasing losses from fires (including those caused by people), drought, and other natural disasters.

Looking back at forest losses shows that, over the last several decades, the state of global forests has deteriorated considerably. Today, forests account for 31% of the world’s landmass, but just 25 years ago, in 1990, they covered 32%. Back in 1990, global forests occupied 4,128 million hectares; however by 2015, this figure was reduced to just 3,999 million hectares. Twenty-five countries lost all of their forests, and 29 more destroyed 90% of their forests.

According to a Yale University study (Mapping tree density at a global scale, 2015), more than 15 million hectares of forests – an area comparable to the territory of Great Britain – are felled every year to meet the current global demand. If this trend continues, in another 20 years, forest areas comparable to the combined territory of Germany, France, Spain, and Portugal will be lost, and by 2300, forest resources will completely disappear.

The loss of forested areas produces irreversible ecological effects and leads to changes in the natural environment, which in turn causes climate change, natural disasters, loss of biodiversity, environmental degradation, and a number of other problems.

In the early 1990s, the world began to wake up to the crisis triggered by the exploitation of forestry resources around the world. The cross-border impact of this issue gradually led to changes throughout the world’s forestry industries.

In 1992, the Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro tackled the state of the environment and the need to transition to sustainable methods to manage natural resources, including forests. The summit’s objective was to “establish a new and equitable global partnership through the creation of new levels of cooperation among States, key sectors of societies and people.”

What underlies the intensive model (which is also referred to as ‘sustainable’, as opposed to obsolete extensive or ‘non-sustainable’ practices) is the principle of minimizing damage to the environment by moving forest industry activities to areas where they do not pose a threat to the local ecosystem. This is combined with reductions in production side-effects by lowering industrial emissions and waste, and improving economic efficiency with better quality recycled materials. ‘Sustainable forest management’ is a modern milestone in the development of forestry methods, ensuring that a balance between social, environmental, and economic objectives is achieved through more efficient management of forest resources and their rehabilitation. Combining these two elements makes it possible to find the most efficient ways of using forest resources for longer periods of time.

Later, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) conducted research that determined that in 2000 nearly 25% of all CO2 emissions resulted from deforestation (which is even greater than the level of damage caused by vehicle emissions). This research, and a number of other similar international studies that emphasized the global challenge of forest loss and set new requirements for all stakeholders to meet the growing demand by consuming fewer resources, led to the adoption of new approaches to managing the forest industry and laid down new ‘rules of the game’ across the entire added value chain.

Russia as part of the global

forest landscape

The current forestry industry landscape is characterized by market globalization based on global supply and demand, an increasingly complex structure of stakeholders, and development of universal international standards for products across the entire added value chain. National and international non-profit organizations and industry associations have assumed key roles in promoting sustainable development ideas, thus becoming one of the new stakeholders in the business. Their core activities are aimed at disseminating and subsequently adapting sustainable practices based on universal international standards.

The introduction of voluntary forest certification has become a key factor in promoting these standards – this process delivers higher quality forest products. Its primary objective is to improve forest management and utilization, making it possible to significantly reduce any negative environmental impact caused by companies directly engaged in forest operations and firms that supply end products. In recent years, voluntary forest certification has expanded significantly to encompass the entire added value chain across various product types. Today, voluntary certification has become essential when shipping competitive products to international markets.

Meeting international quality standards demands a special approach to supply chain management, control of suppliers (and their suppliers), as well as compliance with quality requirements that relate to in-house production. Market globalization and new international standards have also brought about fierce competition, to the extent that products without ‘voluntary’ certification are effectively barred from the market.

As certification requirements continue to expand across the entire added value chain, fewer and fewer products have access to global markets, so the entire sector is becoming less significant for countries that cannot meet modern requirements. This process gradually drives uncompetitive players out of the market, eliminating non-sustainable extensive forest management practices from ‘civilized markets’.

Another qualitative change that contributes to the transition to intensive forest management practices in the global forest industry is the upgrade of technological platforms used in the industry. These have also become radically cheaper, making it possible not only to use state-of-the-art and higher performance machines and equipment, but also to integrate new tech, including IT and even space technologies. This in turn enables improved levels of automation in the sector, reducing the time spent on selected operations and increasing productivity.

In the last 25–30 years, the forest industry landscape has been greatly transformed and the requirements that apply to players have changed, as have technological solutions and the business environment. Unfortunately, a number of indicators show that Russia was not ready for this. Today, Russia has more than 20% of all the world’s forests. Even adjusted for territorial accessibility and the economic feasibility of doing business, only a very small amount of this is used efficiently. According to Global Forest Watch, as of the end of 2011, Russia’s forest industry accounted for $13 billion of the country’s GDP. That figure is comparable to Sweden – a country that accounts for around 1% of all global forests. At the same time, according to WWF, the commercial efficiency of Russian forests is approximately seven times lower than that of developed countries. An analysis of per capita productivity indicators revealed a six-fold difference (productivity in the Russian sector is $22,000 per capita, while the equivalent figure in Sweden is $130,000). Furthermore, Russia mostly exports raw materials, such as round timber. According to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), in 2013, Russia accounted for 15% of total global round timber exports (the highest performer in this market).

Most Russian companies are ranked highly among the leading producers of raw materials, but in forestry, the reverse is true. PWC’s list of the 100 paper mills with the greatest revenues in the world placed the USA’s International Paper first; it was followed by Kimberly Clark (USA), Stora Enso (Finland), Svenska Cellulosa (Sweden), and UPM – Kymmene (Finland). Sappi of South Africa occupied 13th place, Nine Dragons Paper Holdings of China was in 22nd place, Fibria Celulose (VCP + Aracruz) of Brazil was in 33rd place, and Ballarpur Industries of India was in 88th place. Russia is the only BRICS member that was not featured in this ranking at all.

We need to look at global practices for a better understanding of why there is such a gap between Russia’s forest resources and the size of the Russian economy, which, after all, is built on natural resources.

Sustainable competitiveness

Today’s frontrunners, which include the developed countries and several emerging economies who are trying to catch up with them, followed different paths on the way to adopting sustainable practices.

The developed European nations proved to be best prepared for the changes in the industry – legally and socially they were already well on the way to adopting sustainable practices.

In Sweden, for instance, forests have always played an important role in the country’s economy and the everyday life of its citizens. The Swedes decided to focus on forestry potential early on, enabling them to increase the forestry sector’s efficiency. Sweden has been studying best practices in sustainable forest management for more than 40 years.

Numerous studies and government support for the industry resulted in a high level of productivity, and thus, Sweden as a country is now firmly embedded in the list of industry leaders.

Canada accounts for 10% of global forestland located in a climatic zone that is similar to Russia. Ninety-four percent of Canada’s forests are government property, which is also comparable to the Russian model. Today, Canada is the world’s undisputed leader in voluntary forest certification coverage. The share of the forest sector in the country’s economy is estimated at $19.8 billion, which is nearly 1.5 times greater than in Russia. For over 20 years, the Canadian government has placed a particular emphasis on the forest sector and its development; they came up with new initiatives to support it, as well as to study and implement innovations (new work methods, technologies, and so forth).

In China, where forests support around 40% of households, 10% of forests were cut down in the space of three years in the early 1960s, plunging the country into a crisis of deforestation exacerbated by a resource deficit. For more than 20 years, China conducted a large-scale program to cultivate its forest plantations, which now occupy nearly 53 million hectares. Today, the People’s Republic is a world leader in combating deforestation and promoting the rehabilitation of forests. For instance, between 2010 and 2015, China’s forestland continued to grow by 1.5 million hectares every year.

Tropical forests are facing the largest losses, especially in South America and Africa. Brazil offers one of the most salient recent examples. It is one of the richest countries in terms of forest resources, but it was also one of 10 countries that set the greatest negative records for forest losses between 2000 and 2010. In the 1970s and 1980s, Brazil suffered large-scale deforestation brought about by the conversion of large forestlands into pastureland for cattle farming. This initiative was supported by the government in pursuit of high profits from cattle farms. In the 1990s, the effects of forest losses in Brazil led to climate changes and natural calamities even beyond the country’s borders, which required urgent measures to reshape government policy. Research work, government support, and targeted investments created an enabling environment to solve the problem by way of introducing sustainable forest management practices. For instance, as a part of the Acre Sustainable Development Program, which was implemented at a regional level and supported by the Inter-American Development Bank, around $108 million was invested, which made it possible to reduce deforestation from 54% to 14% of total forestlands between 2002 and 2008 (according to the Inter-American Development Bank).

Today, sustainable forest management performance in developed countries and a number of emerging nations show how it is possible to maintain the balance between environmental protection and production efficiency, while setting new quality standards in the industry; in the last five years, the rate of forest losses has dropped by 50%. The experience of the leading countries shows that implementing state-of-the-art approaches to forest management and adopting more modern technological solutions can lead to greater efficiency by way of reduced costs. At the same time, more capital-intensive, innovative solutions and new practices demand greater qualifications from stakeholders as well as special skills, which have become a significant barrier to quality transformations inside the industry. To implement changes, one needs to meet the second pre-condition of competitiveness – incentives are needed to ensure that best practices are used in local markets.

The Russian context

Unlike the countries that have already transitioned to the sustainable forest management model, Russia was slower to respond to changes in the industry. That is partly due to the Soviet legacy, where state statistical data was based on indicators relevant to the old command economy, such as scope of production and products in natural terms. These practices led to detrimental results: between 1965 and 1999, the share of particularly valuable coniferous species in the average logging pool dropped nearly 10% (from 66.6% to 56.9%).

This begs the question of whether Russia has the right environment to develop sustainable forest management practices on a large scale, especially given such a legacy.

Today, there are signs indicating that the forest industry in Russia is gradually moving toward a more sustainable forest management model. Throughout this period, there are signs that awareness of the need to develop sustainable approaches continues to grow. International corporations operating on the Russian market help to expedite this process by introducing global business standards, as did non-profit organizations that could be classified as drivers of change.

Among many international NGOs that support the sustainable forest management agenda, WWF is one of the world leaders. The WWF branch in Russia actively supports the development of voluntary certification, treating it as the most efficient tool to drive the development of forest management in the country from environmental and social perspectives alike. In 2014, the total area of FSC-certified forests in Russia reached 39 million hectares.

The WWF-IKEA Forest Partnership is another positive example in Russia. Their joint work has made it possible to discuss legislative initiatives on a wider scale and to foster debate about illegal logging activities with the government, scientific organizations, and representatives of the business community. Apart from promoting the concept of sustainable forest management and building a dialog with representatives of the forest industry, a decision was also taken to create the Association of Environmentally Responsible Producers (GFTN Russia) and a methodological base was developed to deal with sustainable forest management issues and innovative forestry methods. In the future, this project will serve as the basis for developing a new version of the Russian FSC standard.

International Paper, a global leader, has placed sustainable forest management at the center of its production for over a century. The company consistently improves its sustainable forest management business models while ensuring the ‘sustainability’ of its products, its secondary raw materials, and its supply chains. One of the key tools used by International Paper in its markets, including Russia, is cooperation with local suppliers who are trained to use sustainable forest management methods. International Paper works proactively with small local owners of forestlands. For example, it organizes training sessions and education programs. Thus, the company is expanding its share of locally sourced raw materials produced according to best practices.

However, global companies present in Russia that practice sustainable management methods do not and should not cover the entire spectrum of the market for Russian forest resources. In this respect, Russia faces the daunting task of adopting more scalable intensive forest management practices while ensuring interaction between all institutional leaders to demonstrate best practices and create demand in the supply chain. This requires not only legislative efforts laying down norms that regulate the activities of the forest industry, but also the promotion of modern approaches, sharing available knowledge, and training new industry leaders capable of building and developing sustainable competitive businesses in the forest industry.