Elites on the Wing

The deepening economic crisis is pushing the best minds in the developing world to emigrate. Reversing this trend is a systemic goal for decades to come.

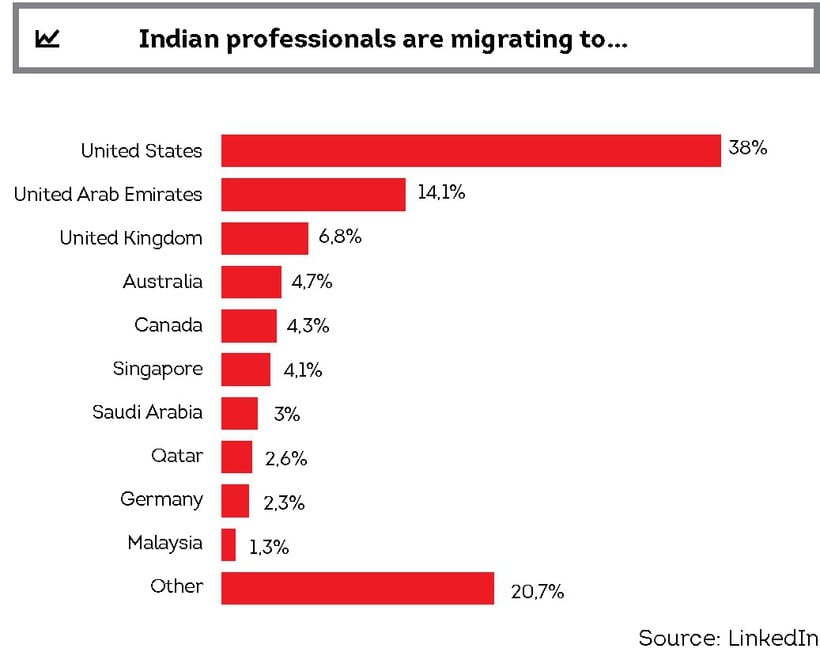

In the middle of August, LinkedIn, the world’s largest professional social network, announced the results of a study examining last year’s migration trends among professionals. India turned out to be the country suffering from the world’s largest brain drain. The number of trained professionals in the country fell by 0.23%. Predictably, the largest flow of Indian skilled migrant workers – 38% – poured into the United States. Indian citizens also have provided nearly a third – 28% – of net inflow of skilled hands into the UAE, the country that emerged as the world leader in attracting talent.

In the middle of August, LinkedIn, the world’s largest professional social network, announced the results of a study examining last year’s migration trends among professionals. India turned out to be the country suffering from the world’s largest brain drain. The number of trained professionals in the country fell by 0.23%. Predictably, the largest flow of Indian skilled migrant workers – 38% – poured into the United States. Indian citizens also have provided nearly a third – 28% – of net inflow of skilled hands into the UAE, the country that emerged as the world leader in attracting talent.

Why are Indian professionals leaving their homeland despite the existing rigid emigration quotas and the heartfelt appeal by Prime Minister Modi to ‘Make in India’? Earlier this January, a survey by The Economist showed that 57% of Indians aged 18 to 22 say they would emigrate to America if given the chance because of economic instability, high crime rates, violence, and corruption in their country. Taking into account the much lower standard of living and income compared to its more developed neighbors, along with a lack of confidence in the prospects for professional and career growth at home, the puzzle pieces of why there’s a surge of emigration blues among professionals in the developing world fall into place.

India is just one significant example that illustrates a strong trend. For example, the number of people in Russia who left the country last year to seek long-term or permanent residence abroad increased by 11% to 53,200 people. Professionals are also running away from Venezuela, which, according to estimates by Caracas-based sociologist Tomas Paez, has lost about five percent of its population of 30 million in the last 15 years. Oil and gas industry professionals, IT engineers, and doctors are leaving the country. That includes Venezuela’s Cuban doctors, who are now heading en masse to neighboring Colombia in hopes of joining the American Cuban Medical Professional Parole Program, which offers an opportunity to work in the United States. The list goes on.

Losses inflicted by brain drain and labor migration are staggering. Therefore, the efforts of some countries to reverse this trend are quite understandable. For instance, a few years ago, Brazil launched a program it called ‘Brain Gain’ to attract scientific personnel; China has started an ambitious plan to attract back the scientists, engineers, and financiers who have left the country – the ‘sea turtles’, as they are called in China – and who are vitally important to the development of a new service-oriented economy.

However, such campaigns have achieved limited success by softening, but not reversing, the negative trend. Doing it today, in the midst of a deepening economic downturn, is much more difficult. This goal is a serious intellectual challenge for authorities, one which requires systematic, long-term efforts to improve their country’s living conditions and stimulate economic growth. Those who are able to determine the right solutions to this problem today will significantly increase their county’s chances of prosperity tomorrow, while, unfortunately, the opposite is also true.