The Big Three of the ‘Third World’

The geopolitical turbulence of the past few years – with crises in the Middle East and Eastern Europe – has brought back the notion of ‘political’ or ‘geographical’ economy. International business leaders have to account for peculiarities in regional and local politics and the struggle for power in their strategies. Yet, politics does not only bring risks; sometimes it creates new and very attractive business opportunities.

The first few months of 2016 were unexpectedly rich in this type of development. First, Iran signed a nuclear deal that lifted most international sanctions. Second, Cuba had a landmark visit from the acting president of the USA, which has launched a series of moves that are ultimately designed to put an end to the longest trade embargo in modern history. Finally, on 1 April 2016, the new democratic government was sworn into office in Myanmar, likely opening up a new economic era for the country.

All in all, the three countries rejoining the world of international trade have a combined population of almost 150 million people and GDP of over $500 billion. Arguably, the world has not experienced an economic event like this since the ‘opening’ of the Soviet bloc in 1990. Likewise, the events of 2016 not only change the trade maps of the world, they have a profound ideological impact.

One may see an attempt to jointly analyze three countries – which are thousand miles apart, share neither language, nor religion, and have few trade ties – as an attempt to enforce historical meaning on a string of coincidences. Yet despite the absence of a truly shared past, there are many remarkable parallels between the three countries.

The keys to regional jigsaws

The three countries were the arenas of some of the most intense colonial struggles of the 19th and early 20th centuries. Iran (then Persia) was hotly contested by Britain and Russia. Both not only annexed substantial chunks of Persia’s territory, but tried to impose political and economic dominance – at the same time, blocking the advances of the other. As a result, the country entered the 20th century with almost no railroads and very limited telegraph connections. The discovery of oil in 1903, mostly in the territory of British dominance, added to the competition’s intensity. Even after the Russian revolution in 1917, the new Soviet government viewed Persia as an important ‘anti-imperialist’ front.

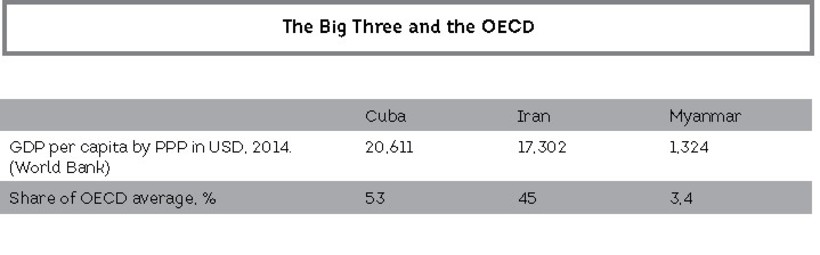

Ideologically-driven development, combined with embargos and sanctions, had strong and complex effects on the socioeconomics of the three countries. On the one hand, their economic growth was relatively slow. On the other hand, the three countries are clearly outliers within the ‘third world’ in certain aspects of development

In the other hemisphere, Cuba was the last big colonial holding of the Spanish crown in the late 19th century. A bloody war for independence in the 1860s resulted in the defeat of insurgents, but it brought little peace to the country. In the 1890s, Cubans’ new anti-colonial efforts were used by the USA as justification to intervene. The result was an independence officially controlled from the outside (under the so-called ‘Platt Amendment’) for almost 30 years. Even after the revolution of 1933 and the formal end of dependence on the North, the country’s economy was heavily dependent on the US market and dominated by US companies.

Myanmar was the center of the most important medieval empire in Southeast Asia, which was also a strong player in the affairs of Eastern parts of India. This brought conflict with Britain (which was also seeking to stop the French advancement in Indochina), and, after three wars (1824-26, 1852, and 1885), the whole of the country fell under British rule. Myanmar (then Burma) was a key front in World War II, namely as the site of a quick initial assault by Japan, which sought to invade British India and cut the supply line from Allied forces to China. Burma claimed independence under Japan in 1943, yet the leaders of the independence movement became increasingly dissatisfied with the Japanese cause and rejoined the Allies in 1944, even at the expense of independence (it was officially reestablished through negotiations with the British Empire in 1948).

The unusual intensity of colonial fights around the three countries was not just a historic coincidence. All three are strategically located at the center of globally important regions – the Caribbean, Southeast Asia, and Middle Asia – making them hubs of economic and political relations. Controlling them was seen in the geopolitical games of 19th century as the key to control of adjacent parts of the globe.

The driving force of society

The turbulence of the countries’ colonial periods contributed strongly to their national mindsets. They each had a strong history of pro-independence struggle, characterized by armed resistance as well as anti-colonial philosophy. This struggle intensified during the Cold War period, as the strategic location made the countries ever more attractive as areas of influence for the socialism and capitalism camps.

In 1951, Iran attempted to nationalize the oil industry in one of the time’s major anti-imperialist moves. The attempt ended in 1953, though, after a military coup backed by the CIA returned the country to ‘capitalism as usual’ mode for a couple of decades – but left a deep scar in national pride. Some five years later, Cuban guerilleros, led by Castro and Che Guevara, ousted the corrupt pro-Western dictator Batista, and, in a short time, the country officially proclaimed the pursuit of socialism. In 1962, after the coup d’etat, the socialist camp was joined by Burma. Finally, in 1979, Iran’s pro-Western (and corrupt) shah was deposed by the Islamic revolution, which was also vigorously anti-American (though the country’s relations with the ‘godless’ USSR were also very strained, especially after the invasion into Afghanistan).

Iran and Cuba’s revolutions proved to be remarkably vivid, surviving the fall of the socialist bloc. In fact, they are among the few nations where strong ideologies remain in today’s largely post-ideological world. Though substantial moves were made in the liberalization of the countries’ economies, they officially remain loyal to the ideas of their revolutionary founding fathers: Fidel Castro and Che Guevara, and Imam Khomeini.

Burmese socialism was shorter-lived. After the 8888 Uprising (8 August 1988) and a military coup, the ruling junta abandoned some of the ideological stances, yet kept the overall authoritarian grip on power.

All three countries had very uneasy relations with Western democracies, resulting in very restricted economic ties. In fact, two of them – Cuba and Iran – were under official trade embargo from the USA, while Iran faced international sanctions from 2010-2014.

Outliers in the ’third world’

Ideologically-driven development, combined with embargos and sanctions, had strong and complex effects on the socioeconomics of the three countries. On the one hand, their economic growth was relatively slow. Cuba’s GDP growth performed better than the Latin American average in the 1970s and 1980s, but it has lagged behind the continent’s tempos over the past 25 years. Burma entered its period of socialism in the 1960s as one of the region’s wealthier countries, but it emerged in the 1990s on the UN’s list of the world’s least developed nations. Since then, the economy has sped up, but it is still firmly in the low-income group. Iran had an especially harsh economic history in the 1980s with devastation caused by the Iran-Iraq war (1980-1988). The country was on a steady growth track in the 2000s with the development of private enterprise, yet sanctions and falling oil prices in the 2010s created their share of economic difficulties, and the country’s GDP was declining by an average of 2.3% from 2010-2014.

On the other hand, the three countries are clearly outliers within the ‘third world’ in certain aspects of development. They have strong educational systems, which result in illiteracy rates of almost zero, not to mention boast relatively high university enrollment. Cuba, in particular, is recognized for its medical and pharmaceutical schools, plus the foundation of one of the best health care systems in the developing world. Iran, on the other hand, demonstrated significant technical capabilities through its nuclear and missile programs, which they have now converted to civil use through a booming IT industry. Myanmar also made scientific development a high priority, especially in a generally low-income context; since 1955, the country has strived to develop national nuclear research, with plans being revived in 2007 with the help of Russia.

The needful problems

However, all three countries have a mass of classic third-world problems, which challenge their economic development. Infrastructure is definitely the major one. Road density in Iran stays at 10% of the OECD average; Myanmar has half as much. Even Cuba – which is very compact in size, with a maximum possible distance of less than 1,500 km – is at about one-third of the OECD level (and statistics fail to capture the actual quality of the pavement, which is way below the standards of a modern road).

Additionally, Cuba and Myanmar depend on imported fuel, despite some recent developments in national extraction. As a result, electricity is rather scarce (Myanmar consumption per capita stays at three percent of the OECD level). The two countries lack important industry, with too high a contribution from agriculture. Iran is much more industrialized (e. g. it produces more cars than Italy per year); however, most of its industrial assets base is either old, low-tech (due to restrictions on advanced equipment imports), or both. The problem of aging assets is also very acute in Cuba: The American cars of 1950s, so beloved by tourists, are fuel-inefficient and expensive to maintain.

Overall, the three economies need a massive influx of investment, and given the relatively low national wealth, it is only through foreign funds that the problem can be solved. This is well understood, and even the most devoted revolutionaries now take a very pragmatic approach to foreign money.

A major source of risk

Yet foreign investments usually seek strategic stability. This becomes an increasingly scarce resource all across the world, and Iran, Cuba, and Myanmar are no exception.

Cuba seems to be a political question mark, even in the short-term. Raul Castro, who acts as the leader of the country now, may have created a certain fan club around the world by skillfully avoiding the hug of Barack Obama, but the reality is that both Castro brothers will be out of power in a few years. No succession plan has been made public – if there is one at all. So, it seems that no one inside or outside of the Isle of Freedom has a strong idea of who will be ruling the country in the 2020s – or how.

Myanmar seems radically different in that its citizens have finally won a free vote and have the first democratically elected government in more than half a century. It is probably the strongest one in the country’s new history, under the unofficial leadership of Aung San Suu Kyi, the popular and influential Nobel Prize winner, daughter of the official founder of the nation and ex-political prisoner. Still, the current constitutional order gives the military significant uncontrolled power – enough to block major democratic developments. The economy is also widely believed to be controlled by the military through the assignment of ex-rank to all the important posts in ministries and companies.

Iran, somewhat contrary to common Western opinion, is a much more stable and viable democracy. Its religious leaders hold significant power, but they are generally accountable to law and society at large. A way to think of them is to add just another branch of power to the classic Western model of legislative-executive-judicial. This is not to say that the country does not have intense ideological battles between conservatives and reformists. Indeed, the front of the debates goes across any possible life issue – from whether the secular powers should impose the hijab to could the Western countries be trusted in the process of forthcoming privatization. For the moment, the reformists are gaining ground, yet it is not only the country’s internal politics that will decide who will have the final say.

The long-term success of the reformists in Iran depends very much on further achievements in international relations, translating into something visible for business and public opinion: travel procedures simplified, contracts signed, investment landing on bank accounts, more international brands in shop windows, etc. The problem is that the West has its own strong group of conservatives in everything relating to Iran (and also to Cuba). The forthcoming presidential elections in the USA may have an especially disturbing effect, as Barack Obama was widely criticized for excessive liberalism towards ‘rogue states’. If American rhetoric and actions return to the mindset of the early 2000s, the Iranian and Cuban enthusiasts’ hope of international openness are sure to suffer a very serious blow.

An optimistic scenario

However, an optimistic scenario seems today to be more likely. If the three countries really rejoin the global economy, there will be massive gains on both sides. On the one hand, foreign investment can lead to exploration of mineral wealth. The global obsession with oil in the late 20th century has obscured the fact that Iran and Myanmar are likely to have very important deposits of metals that remain undiscovered. Iran estimates that less than 10% of its territory was properly explored, and the figure for Myanmar is still lower. Cuba has world-class deposits of nickel, which are definitely underexplored.

Agriculture is another area of important opportunity. All three countries have favorable climate conditions, yet agricultural production is very inefficient by modern standards, due to outdated techniques and logistics. In particular, Cuba can benefit from the global push for biofuel – distilling ethanol from sugar cane, thus hedging against the volatility of global sugar markets – but this requires an injection of both technology and investment.

Iran, somewhat contrary to common Western opinion, is a much more stable and viable democracy. Its religious leaders hold significant power, but they are generally accountable to law and society at large

There are growing opportunities in the three countries as consumer markets. Iran is especially notable in this regard with its population of over 70 million, who are mostly young and increasingly westernized in lifestyle. At the same time, Cuba definitely has to scrap its picturesque oldtimer cars and replace them with modern and efficient models. And private construction is a booming industry, be it in Mandalay and Yangon, Tehran and Shiraz, or Havana and Santiago.

Yet the major opportunities for the three countries lie in the geo-economics – this peculiar feature being key to regional jigsaws. With the advancement of multi-modal transportation, Myanmar and Iran both provide excellent land routes to the Indian Ocean – from inner China and Europe and Russia, respectively. Cuba in turn can try to reclaim the role of regional hub for oil refining and off-shore high-tech manufacturing (e. g. in pharmaceuticals) that it had in the 1940s and 1950s.

Interestingly, the three economies become the arena for a new type of global business competition – between the ‘classic’ multi-nationals of the West and the ‘emerging MNCs’ from countries like China, India, or Russia. Chinese involvement is particularly strong in infrastructure development, while Russian companies are traditionally important players in explorations and extraction of minerals. On the consumer side, one can see more and more brands from emerging markets filling shop shelves and windows. Up to this moment, the ‘East’ had enjoyed important advantages in the markets of Iran, Cuba, and Myanmar – both through ideological closeness and price effectiveness. Will the ‘Eastern’ companies continue gaining market share in the increasingly open economic context? This will be a good test of their international competitiveness. The consumers and economies at large will definitely benefit from this new type of competition, though some local industries may find themselves being strongly pressed on the home ground. Still, in this new era of Iran, Myanmar, and Cuba’s histories, being placed at the heart of world’s important regions can become an opportunity, not a threat.