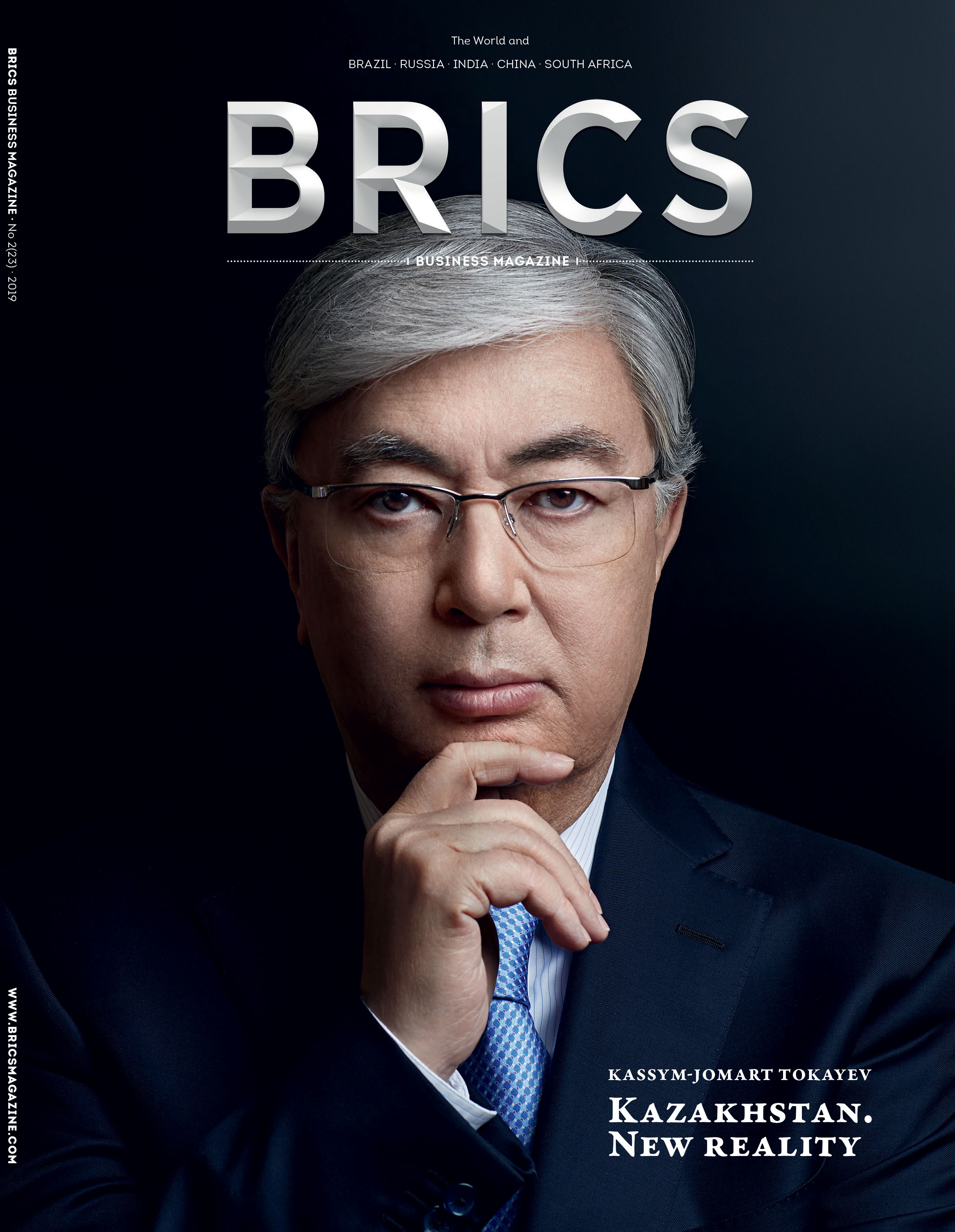

BRICS Business Magazine English Edition No.2(23)

About BRICS Business Magazine

BRICS Business Magazine is a bookazine

—

a book-like magazine – addressed to global investors, businessmen, politicians, and experts.

A business and humanitarian

publication on rapid-growth markets, it is issued four times a year and

explains how to understand others.

The goal of this project is to organize a direct information exchange between the BRICS countries and other emerging markets.

We define a bookazine as a thick magazine with complex printing which is designed for slow reading and filled not in accordance with a constant set of sections, but rather in accordance with the topics chosen. Our bookazine includes (with occasional exceptions) three main kinds of data:

- essays and columns that would fit into “Opinions” or “Recommendations” sections

- indices, ratings, and rankings

- business cases

Industry and event projects as well as investment guides are featured as special add-ons.