Alejandro Aravena A Visionary Architect Who Wants to Change the World

Bruce Watson

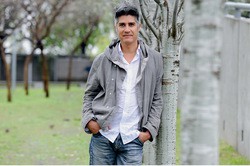

When we first meet, Alejandro Aravena is sitting in a New York café, sketching in a journal and nibbling on a cheese omelette. Architects tend to straddle the line between art and engineering, and the blend plays out in the pages of Aravena’s journal, where cryptic notes and equations sit with scribbles and sketches. Here there’s a drawing suggesting the line of a roof or the arch of a doorway; there a page of notes and comments.

But Aravena’s plans extend far from the standard considerations of building and line, into theories of social organisation and civic engagement. He’s designing buildings, but he’s also designing cities they will occupy and the livelihoods of the people who will live in them. This becomes clear as, from time to time, Aravena flips through the book, noting something, sketching an idea, then laying it aside.

As previous interviewers have pointed out, Aravena bears no small resemblance to the comic book character Wolverine. His salt-and-pepper hair evokes the trademark Wolverine flip, and the intensity in his grey eyes brings to mind the character’s feral energy. Excitement and intensity pour off him as he discusses the place of design in society, and its ability to change lives.

Cities, Aravena argues, may be the best tool that planners can use to extend economic opportunity to the less privileged, without resorting to heavy-handed tools like income transfers, and without “guilt or paternalism.” The key, as with any other form of design, lies in synthesising disparate elements, embracing contradiction, and realising that, in the end, cities must balance human rights with human responsibilities

In fact, Aravena’s friendliness creates a moment of cognitive dissonance. This, after all, is one of the world’s leading architects, a man who has won some of the most prestigious architecture prizes in the world, including the Marcus and the Erich Schelling, and is on the jury for the Pritzker prize. He has taught at Harvard, and his high-profile buildings have been erected all around the world, to great acclaim.

Given the opportunity, many architects would steer conversation toward their most prestigious work. And, certainly, Aravena has more than enough celebrated architecture to discuss: his current and recent projects include an innovation centre in Santiago, corporate buildings for Novartis and Vitra, and a proposed stock exchange in Tehran. But, rather than talking about his prestigious commissions, Aravena wants to talk about social housing.

Much has been written about Aravena’s social housing projects, which combine innovative architectural design with a social framework that encourages personal investment on the part of the inhabitants. In fact, his company, Elemental, tries to evenly divide its work between social housing, large-scale civic construction, and private contracts. While these three elements may seem contradictory, Aravena revels in the contradictions, which, he argues, fuel his practice.

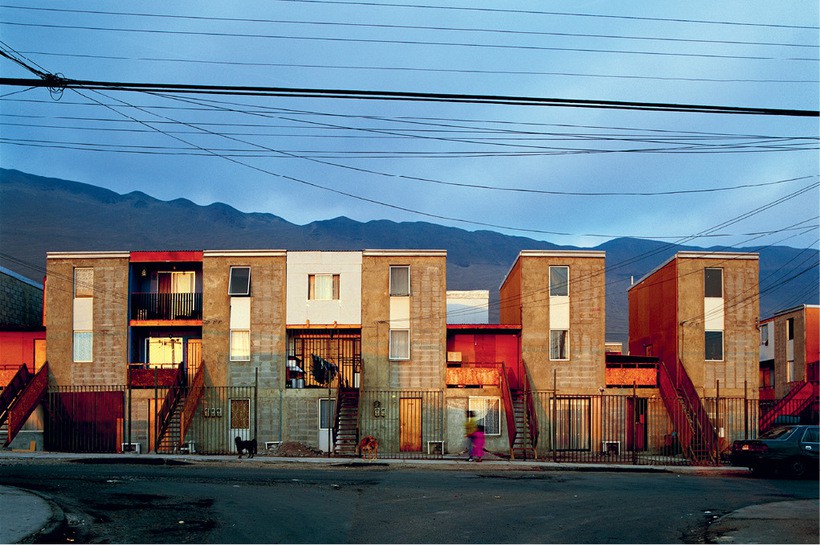

The power of contradiction emerges as Aravena tells a story about a social housing project he recently built in the north of Chile. The project, located near the centre of a city, replaced a slum largely occupied by people who worked for the city’s richest citizens. After completion, Aravena toured the project with the CEO of Chile’s national gas company, one of the wealthiest men in the country.

They came across a woman who was moving into one of the units. When they asked her how she felt about the new housing, she was effusive, and proceeded to tell them about her four children, two of whom were in college, one of whom was in Chile’s top high school, and one of whom was in the second year of law school. The CEO, surprised, pointed out that his grandson was in the same law school programme. They soon realised that the two young men were in a study group together.

The key to this story, Aravena emphasises, is that the location of the ghetto, and later of the social housing project that his company built, created opportunities for the woman and her fellow workers. “A typical housing project wouldn’t be in the best part of the city,” he notes. “It would be two hours away. If she lived there, she could forget about sending her kids to college. Forget about being in contact with the rich grandson. Forget about having access to the best high school in the country. So her daughter, who was about to leave high school to go to medical school, would never have had access to university.”

This story gets to the heart of Aravena’s concept of cities, and architecture as a tool for social change. “Inequalities are not just an economic issue,” he explains. “They’re a cultural issue. The role that cities can play in creating or not creating those opportunities, it’s irreversible.” If designed properly, he says, “cities can be a great tool for the efficient amelioration of quality of life problems”. “They are a great shortcut for creating equality.”

The key, Aravena argues, is that cities, and architects, must not shy away from the stresses created by competing forces like poverty and wealth or public and private construction. Rather than argue about whether to design cities for the needs of their poorest citizens or the egos of their wealthiest, Aravena posits, the answer might be to do both. At Elemental, he says, “we do not fear that, in this initial entry to the problem, we have forces that may seem contradictory. If you trust the synthesis of design, you don’t fear contradictory forces.” Of course, good design isn’t cheap, “it requires time and it requires effort,” he says.

This synthesis of disparate elements is borne out in Elemental itself. The company is co-owned by three groups: the private architects who work for the company, a Catholic university, and Chile’s largest oil company. Aravena notes that the combination of these stakeholders, each with a very different agenda, helps his company to maintain its relevance, and its connection to the broader society. “One of the biggest mistakes in architecture is that we’re expecting society to be interested in the specific problems of architecture.” Instead, he argues, architects “need to adjust to what society is discussing. We just provide the forms that can translate their problems into solutions.”

In the case of social housing, he argues, one problem is that many of the architects translating resources into solutions are either unskilled or unengaged. “One of the crucial factors we found that makes social housing so poor is that nobody is paying to think about it better. Good design costs money, but social housing is either done pro bono, or by people who couldn’t find jobs in other places.” This lack of resources and engagement leads to poor results, which can often be felt for generations. “This is equivalent to brain surgery. If you make a mistake, it’s irreversible. If you screw it up, you screw it up for thousands of people, over multiple generations.”

One reason that top-level architects shy away from social housing is the lack of resources. In his social housing projects, Aravena routinely works with a hard cap of $10,000 per unit, a sum that has to pay for both the building and the land it sits on. But, while many architects would shy away from such constraints, Aravena argues that the “discipline of scarcity” leads to a clarity of vision and quality of design that would be impossible under other circumstances. Designing social housing, he claims, has taught him to “leave out what is not strictly vital. Be precise. Avoid arbitrariness.”

This precision, Aravena notes, is borne out in the name of his company. “An elemental project is your best. Period. It is something that goes to the most essential core of something. This is something that is desirable, no matter how many resources, or how much freedom you have.”

This elemental process works both ways. While Aravena’s notion of precise, clean social housing design informs his higher-profile projects, the professionalism of those undertakings also influences his social housing designs. “Novartis requires the best possible design. Building their headquarters has trained my designer muscles to their limit.” This, in turn, plays out in his social housing: “When we do social housing, we enter it as designers, not as policymakers, not as an NGO. If I’m going to make a difference, I’m going to do it as a designer. That’s why I need my muscles trained.”

Ultimately, Aravena argues, cities may be the best tool that planners can use to extend economic opportunity to the less privileged, without resorting to heavy-handed tools like income transfers, and without “guilt or paternalism.” The key, as with any other form of design, lies in synthesising disparate elements, embracing contradiction, and realising that, in the end, cities must balance human rights with human responsibilities.