Sense of Location

“National reputation cannot be constructed; it can only be earned,” says territorial branding guru Simon Anholt in his book Places: Identity, Image and Reputation. “In other words the multi-million dollar investments channeled by governments towards building their countries’ branding through advertising and PR campaigns are unlikely to yield any tangible results in the long term,” he writes. So, what happens then? What should developing nations do to promote their image in the eyes of the international community? BRICS Business Magazine here publishes excerpts from Anholt’s Places, with answers to these and many other questions.

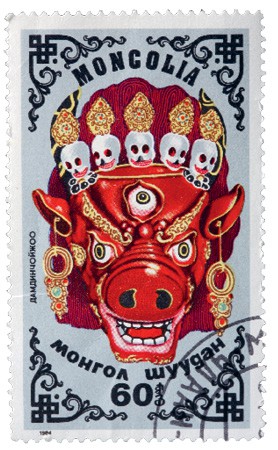

Pakistan and Mexico

Pakistan and Mexico

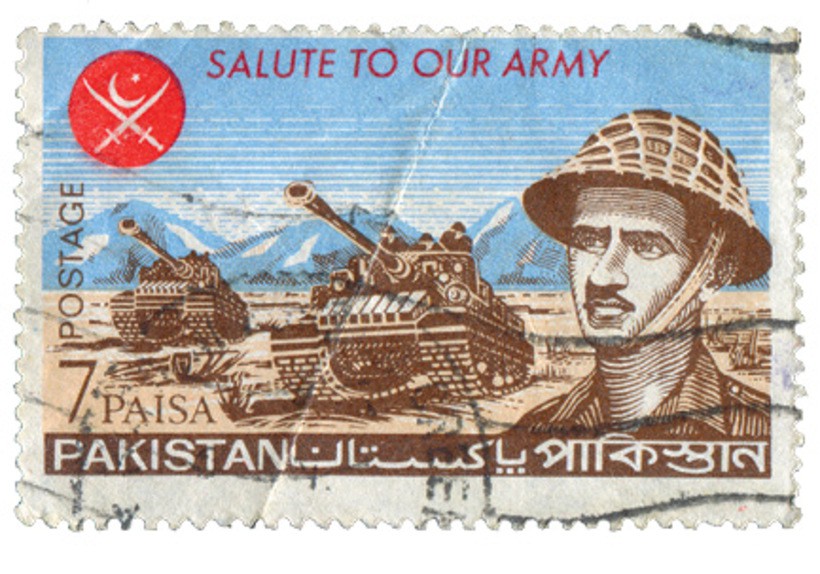

Talking about Pakistan’s international image may sound irrelevant, even absurd, at a more than usually troubled time in the country’s history, but the simple fact is that every country on earth depends on its good name in order to achieve its aims in the globally connected world we live in today.

At some point in the future, when things have stabilized a little, Pakistan will find that its ability to interact effectively and profitably with other countries will depend to a considerable extent on its good or bad image; its ability to lure back its most talented emigrés and stem the tide of those leaving to study and work abroad; its ability to attract business and leisure visitors as well as foreign investment; the quality of its engagements with other governments and multilateral agencies: all of these transactions will be considerably easier if Pakistan’s reputation improves, and they will prove a constant, uphill struggle if its reputation remains as weak and negative as it has become today.

With daily violence, a bitter struggle against insurgent elements along the Afghan border, and constant political and social upheaval, the international image of Pakistan is in tatters, and is probably the last thing on the mind of Pakistan’s government as they fight for political survival and ascendancy over the Taleban. But there will come a day when the country needs to think again about restoring its damaged reputation: and the longer the country remains in freefall, the harder a task this will be.

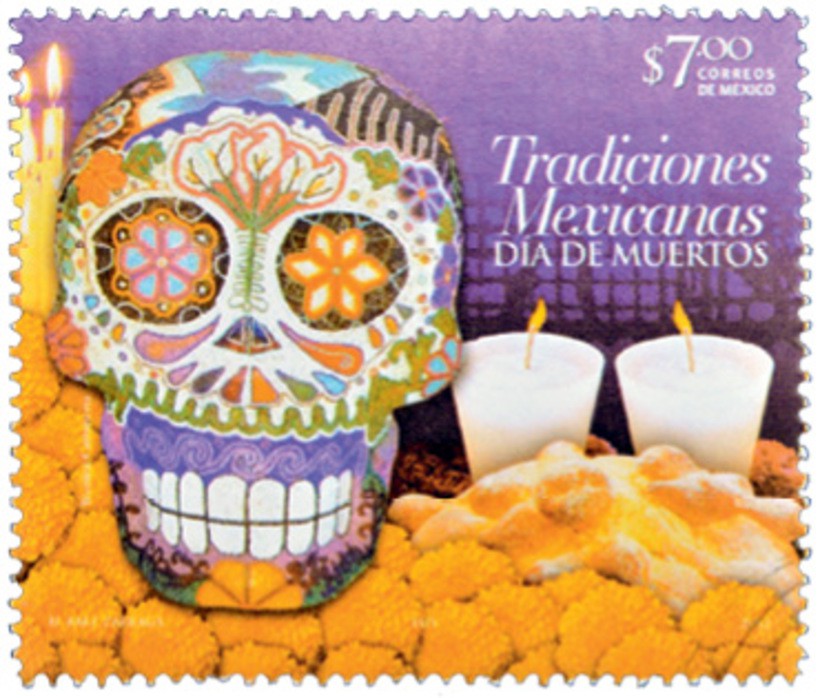

The Mexican government probably wasn’t primarily concerned with its international reputation either, when the southern state of Tabasco lay partly under water in 2008 or when swine flu threatened to develop into a global pandemic in early 2009: at such moments, its main concerns were rather more practical and immediate. But when major natural disasters happen, people often do worry that it will damage their country’s international interests by spoiling its image, and they are usually wrong. Most of my research suggests that the things which happen to a country (such as natural disasters, terrorist attacks or epidemics) seldom affect people’s perceptions of that country in any profound or lasting way: what changes the image of a country far more is how the country responds to such crises, and what the government, the people or the companies in that country do – especially when it has an impact on people in other countries.

The population of Pakistan quite rightly feel that they are as little to blame for their country’s current woes as the people of Mexico: but they are nonetheless likely to suffer the consequences of them for very much longer. Mexico will recover from floods and flu, people will rebuild their lives and their communities, and life will return to something like normal for the majority of those affected; before very long, world opinion will focus on another disaster, and will forget the Tabasco floods and swine flu, just as it has begun to forget Pakistan’s devastating earthquakes of 2005.

The population of Pakistan quite rightly feel that they are as little to blame for their country’s current woes as the people of Mexico: but they are nonetheless likely to suffer the consequences of them for very much longer. Mexico will recover from floods and flu, people will rebuild their lives and their communities, and life will return to something like normal for the majority of those affected; before very long, world opinion will focus on another disaster, and will forget the Tabasco floods and swine flu, just as it has begun to forget Pakistan’s devastating earthquakes of 2005.

But because Pakistan’s present troubles are man-made, their effect on the world’s perceptions of the country will persist, and Pakistan will struggle for decades to present itself to the world as a responsible, trustworthy ally and partner in trade, tourism and politics. Acts of God can harm a country in many ways: but it is acts of men that cause the most lasting damage.

Kenya

An article from the Nairobi Business Daily in 2008 told how the ‘Brand Kenya’ initiative, despite a great deal of goodwill, failed to get off the ground. Various reasons were given for the project’s lack of momentum, including the absence of sufficient political will: it is certainly true that unless such projects have the sustained and personal backing of the head of government and, preferably, the head of state, they are unlikely to go very far or last very long. Without such authority and commitment, there is little incentive for the various stakeholders to collaborate, and they will soon revert to ‘business as usual.’

What was striking about the article, however, was the unquestioned assumption that a lack of funds was the real reason for the failure of the project. Various people were quoted, mentioning staggering sums of money, and pointing out that these sums were inadequate because they were less than the average corporation spends on advertising, and therefore well below the minimum required to ‘brand’ a country.

This seems to be missing the point. Countries can’t simply buy their way into a positive ‘brand image’ – especially if, like most African countries, their current image is very negative or very weak. Every country that has ever succeeded in noticeably improving its reputation – South Africa, Ireland, Japan, Germany, Spain – has done so as a result of economic or political progress. The advertising and PR campaigns which occasionally accompany these ‘branding miracles’ are never the cause of them, although on occasions they have been some help in making people aware, both inside the country itself and abroad, of the changes that are taking place, and thus shortening the normal lag between reality and perception. This is a classic case of confusing correlation and causality: claiming that the advertising causes the new image is like noticing that I open my umbrella whenever it starts to rain, and then hailing me as a magician because I can make it rain just by opening my umbrella.

This seems to be missing the point. Countries can’t simply buy their way into a positive ‘brand image’ – especially if, like most African countries, their current image is very negative or very weak. Every country that has ever succeeded in noticeably improving its reputation – South Africa, Ireland, Japan, Germany, Spain – has done so as a result of economic or political progress. The advertising and PR campaigns which occasionally accompany these ‘branding miracles’ are never the cause of them, although on occasions they have been some help in making people aware, both inside the country itself and abroad, of the changes that are taking place, and thus shortening the normal lag between reality and perception. This is a classic case of confusing correlation and causality: claiming that the advertising causes the new image is like noticing that I open my umbrella whenever it starts to rain, and then hailing me as a magician because I can make it rain just by opening my umbrella.

Creating a better image for a country is often far cheaper and always infinitely harder than people imagine. It’s about creating a viable yet inspirational long-term vision for the development of the country and pursuing that aim through good leadership, economic and social reform, imaginative and effective cultural and political relations, transparency and integrity, infrastructure, education, and so forth: in other words, substance. The substance is then expressed, over many years, through a series of symbolic actions which bring it memorably, effectively and lastingly to the world’s attention.

Nations have brand images: that much is clear. And those brand images are extremely important to their progress in the modern world. Brand theory can be helpful in understanding those images, measuring and monitoring them, and even investigating how they have come about. But brand marketing cannot do very much to change them. Change comes from good governance, wise investment, innovation and popular support.

What created the image in the first place? Not communications. What can change the image in the future? Not communications. What Kenyans need to understand is that winning a better image is not only a matter of persuading government to get involved in the issue: it is the primary responsibility of the government, and that image is the direct consequence of the leadership and good governance given by the government – or the lack of it.

Creating a more positive national image is not a project that government needs to take an interest in. Earning a more positive national image is what good governance is all about.

Latvia

Latvia faces a problem which is common throughout its neighbourhood: the urgent need to try and rebuild a national identity and reputation which the Soviet Union almost entirely erased.

This is one of the less recognized impacts of Soviet rule: by cutting off all movement of trade, culture, people and communications between its satellite states and the rest of the world, the Soviet system effectively destroyed the public identities of these countries. Now, they have to painstakingly rebuild those identities, brick by brick.

The lucky countries are the ones that were left with beautiful cities – like Riga, Prague, Ljubljana, Krakow and Budapest – as they have been able to attract plenty of tourists to their cities and thus re-open a dialogue with the West, and beyond: for the Ryanair generation, the appeal of such places has little to do with their past, and everything to do with their nightlife, their affordability and their cool. The countries and cities without obvious tourist appeal and without budget airline links have a far harder task ahead of them.

Spain, too, had an easier job ‘re-introducing’ itself to Europe after the death of Francisco Franco, because his rule was short enough for Europeans still to share a common memory of Spain as a dynamic, modern European democracy. People only needed to be reminded of this, and to be reassured that Spain was once again open to the world and open for business, and Spain could pick up the pieces of its shattered reputation again. But few people outside Eastern and Central Europe have any conception of countries like Poland, Romania, Bulgaria, Hungary or the Baltic States as free countries with their own proud histories, cultures, personalities, products, landscapes, traditions, languages and people.

Spain, too, had an easier job ‘re-introducing’ itself to Europe after the death of Francisco Franco, because his rule was short enough for Europeans still to share a common memory of Spain as a dynamic, modern European democracy. People only needed to be reminded of this, and to be reassured that Spain was once again open to the world and open for business, and Spain could pick up the pieces of its shattered reputation again. But few people outside Eastern and Central Europe have any conception of countries like Poland, Romania, Bulgaria, Hungary or the Baltic States as free countries with their own proud histories, cultures, personalities, products, landscapes, traditions, languages and people.

There are few bigger crimes than what was done in the name of Communism during the last century: entirely obliterating a country’s good name and its history and identity, along with the centuries of its progress and cultural growth, and like some global game of snakes and ladders, sending it back to square one to fight for recognition in a busy, highly competitive, and largely indifferent world.

And speaking of board games, the US company Parker Games launched the Monopoly World Edition website last year, where people could vote for the cities that were to be featured in the new Global Edition of the game. The contest was announced in a Latvian newspaper, and Riga soon rose from 46th to 2nd position.

Parker Games presumably then was faced with the dilemma of either assigning some of the most valuable real estate on the board to this virtually anonymous ex-Communist city, or else risking international opprobrium and overriding the popular vote: naturally, thousands of the good citizens of Riga had got voting, and succeeded in pushing their city way up the rankings. I say ‘naturally,’ because almost nothing is more natural – or more powerful – than people’s love of their own city, region or country.

Parker, I’m glad to report, did the honourable thing: Riga now sits proudly alongside Montréal on one of the two coveted dark blue squares on the board – and who knows? Perhaps a generation of children around the world are growing up with an unshakeable conviction in the back of their minds that Riga is one of the world’s poshest cities.

A similar phenomenon was observed last year when the Swiss film-maker and adventurer Bernard Weber had the idea of creating a ranking for the ‘New Seven Wonders of the World.’ The event resulted in over one hundred million votes being cast around the world, as ordinary people voted frantically to get ‘their’ national landmark recognized as one of the new seven wonders. As I write in mid-2009, Weber’s firm is launching a new initiative: the New Seven Wonders of the Natural World, and they are talking coolly of receiving one billion online votes.

It’s striking because such events are somewhat unfamiliar. But if you think about it, equally dramatic displays of widespread and energetic patriotism are regularly triggered for every football World Cup, every Olympic Games, and to a lesser extent for contests such as ‘Miss World.’ Whenever people have an opportunity to boost the profile of their home town or home country, they do it, and in huge numbers. In the Eurovision Song Contest, where people can’t vote for their own country, we see instead the utterly compelling spectacle of hundreds of thousands of people practising real-time public diplomacy, and voting for the countries they most wish to appease, flatter or flirt with.

Clearly, powerful forces are being unleashed here, and in a way it’s reassuring to find that in our age of globalization such a simple and elemental instinct as patriotism is alive and well – and especially encouraging that it usually manages to find its outlet in harmless fun.

Such contests are undoubtedly ‘good branding’ for the places that do well in them: in one way or another, they will help to raise the profile of the place, increase tourism numbers, encourage other kinds of commercial interest such as foreign investment and trade, and boost the number of people who decide to study, work and relocate there.

But all those millions of ordinary citizens certainly aren’t voting for their home town because the tourist board has asked them to (most people are blissfully unaware that their city or country even has a tourist authority, and many even complain about the number of foreign visitors cluttering up their streets) or even because they necessarily see a direct connection between their vote and their future prosperity. It appears to be something purely instinctive, an almost automatic outpouring of group pride, and the expression of our own identity through the place that made us.

As I first reported in the 3rd Quarter Report of the 2005 Nation Brands Index, the way in which people rank the ‘brand images’ of their own countries follows a fascinating pattern. Every country in the overall Top Ten of the NBI ranks itself first, while every country in the bottom 30 rates one or more other countries higher than itself – with the exception of two of the fastest-growing economies in the world, India and Ireland. It’s impossible to say whether this is cause or effect: do people rate their own country highly because they know how admired and admirable it is, or does the fact they rate it so highly help it to become admired and admirable?

The reality is that it’s probably both at the same time, and there is some kind of feedback loop going on here. Ask 100 chief executives the secret of their company’s strong brand, and half of them will probably tell you that it’s the belief of their own staff in that brand and its values. Loyalty builds success, and success builds loyalty, and no place on earth – city, town, country, village or region – can hope to make others respect and admire it unless it first respects and admires itself.

But of course there’s a catch. As with anything else that involves getting large numbers of people to make the effort to do something they don’t normally do – even if it’s only a matter of visiting a website and clicking on a button – there is a limit to how many times this force can be successfully unleashed. Yes, people undoubtedly do feel a strong pride in their own country or city, but their energy to express it is, like anything else, limited. You can’t keep stoking the fire of patriotism forever: unless provided with new fuel, it will eventually die down and burn out.

Governments should reflect on this. Poking the embers of a population’s love of their country will, nine times out of ten, produce a blaze, and this is a trick that any child can perform. But keeping the fire going for generations, without burning the house down, is a steeper challenge altogether.

Albania

Albania, just like America, finds itself battling against a negative image, its officials also asking ‘why do they hate us?,’ and also complaining that the good stories just don’t seem to be able to get out.

Albania is in many ways the typical case of a transition state whose reputation lags painfully behind the reality: since the end of Communism, the country has made notable social and economic progress, but this appears to have had almost no impact on popular perceptions of the country. The ‘professional’ audiences – such as investors, diplomats, tour operators, bankers and business people – are, of course, better informed about the place, and some of them are quite excited about Albania’s prospects, but the general public is 20 years behind the curve. From the way most Europeans talk about Albania, you would think that King Zog was still on the throne.

Albania’s problem is the fact that most people are far too busy worrying about their own countries and their own lives to give much thought to a country they know little about and will probably never visit, and they are unlikely to go to any trouble to update the shallow, convenient, prejudiced narrative they hold in their heads about such places. Modest progress, growing stability and sensible reforms don’t make headlines and don’t interest people who have no personal connection with the place. Evil tyrants, self-styled monarchs, repulsive regimes, shocking repression: these are the stories that make the media and become the common currency of a country’s international image.

Albania’s problem is the fact that most people are far too busy worrying about their own countries and their own lives to give much thought to a country they know little about and will probably never visit, and they are unlikely to go to any trouble to update the shallow, convenient, prejudiced narrative they hold in their heads about such places. Modest progress, growing stability and sensible reforms don’t make headlines and don’t interest people who have no personal connection with the place. Evil tyrants, self-styled monarchs, repulsive regimes, shocking repression: these are the stories that make the media and become the common currency of a country’s international image.

If I’ve learned one thing in the years I’ve been working in this field, it’s the sad, simple fact that public opinion will never voluntarily ‘trade down’ from a juicy story to a boring one.

Meanwhile, back across the Atlantic, successive public diplomacy officials, with their energetic and well-meaning attempts to communicate how tolerant and benign the USA really is to publics that, largely, detest the place – and for, largely, very good reasons – were suffering from the same misapprehension as the government of Albania: both thought that the good stories would kill the bad ones.

They were both wrong. Strong stories can only be killed by stronger ones.

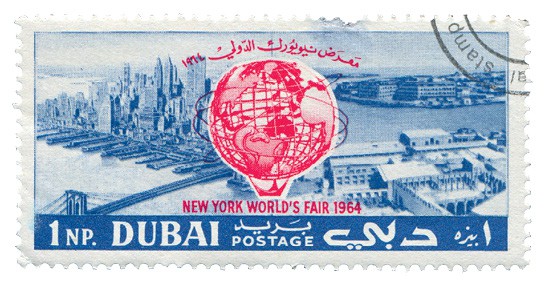

Bilbao and Dubai

People often ask me whether commissioning a big, glamorous new building will ‘brand’ their city. The answer is that it depends why you’re doing it, and how original the building really, objectively is. If the building is highly expressive of something clear and interesting that your city is telling the world about itself – like the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, the Sydney Opera House or the Kunsthaus in Graz – then it might be a very effective piece of ‘branding’ (although it will achieve nothing on its own – it has to be one well-chosen part of a very long-term series of substantial actions that make the story real). If, on the other hand, it’s done for its own sake and there’s no real long-term strategy behind it, it will add nothing to the city’s overall image at all.

Most of the ‘trophy buildings’ built in places like Dubai aren’t expressive of anything in particular: they are just very large glass and steel filing-cabinets which, if they communicate anything at all, are simply monuments to money, power, modernity, technology, and the desire to show off. You need a veritable forest of such buildings before they really mean anything – and even then the only meaning is how much money there is in your city.

‘Make me a landmark building’ is no kind of brief for an architect: but ‘tell the world our story’ might be. Buildings must say something about their city and the country, or they are just bricks and mortar. Or steel and glass.

Asia

Asia

The level of interest in the images and reputations of places continues to grow, and apparently nowhere faster than in Asia. More money is being spent on various kinds of ‘reputation management’ – some of it wisely, but much of it not – by Asian cities, countries and regions than anywhere else on earth. In the rush to stake a claim in the new global economic order, countries from Bhutan to Oman and from Kazakhstan to Korea are talking about their ‘brands’ and attempting to wield some kind of influence over them.

Many of these countries are simply trying to ensure that their international reputations keep pace with the rapid growth of their economic and political power. Others believe that their strongly negative reputations are undeserved, and obstruct their progress.

Still others believe that if only they could have some kind of image, and escape their current anonymity, they would be able to participate more effectively in the global marketplace.

In Asia as in every other part of the world, one sees governments falling into the same traps when it comes to national image and reputation: the ‘naïve fallacy’ that national image can somehow be built, reversed or otherwise manipulated through marketing communications; and the confusion between ‘destination branding,’ which is a kind of sophisticated tourism promotion, and ‘nation branding,’ which is usually understood as the management of the country’s overall reputation.

One of the most prominent cases in Asia is Malaysia’s long-running tourism campaign, featuring the slogan ‘Malaysia, Truly Asia,’ which is often (wrongly) cited as a classic case of successful nation branding. In fact, this is destination branding, carried out with the specific intention of increasing visitors to the country.

It was never intended, nor could it really aspire, to impact directly on the world’s overall perceptions of the country, although of course there are plenty of opportunities for indirect impacts on the country’s ‘brand image’ – not least the simple fact that if more people visit the country and enjoy themselves, they are more likely to spread the word and create a positive ‘vibe’ about the place.

A more rigorous habit of distinguishing between sectoral promotion – such as tourism, exports and investment promotion – and ‘nation branding,’ is an urgent need amongst the community of scholars, commentators and practitioners within this field, in Asia as elsewhere.

The idea of place branding in Asia is commonly associated with tourism today, since many Asian countries are now discovering that a healthy economy depends on a broad spread of risk: the countries that have traditionally relied on exports for their foreign revenues, such as Japan and South Korea, are now urgently attempting to build their visitor numbers, while the countries whose economies – and images – have tended to focus on their appeal as a destination, such as Thailand and the Maldives, are equally keen to broaden their image to embrace foreign direct investment, exports and other sectors. Image goes hand in hand with economic development: a country that is strongly associated with certain sectors will always trade at a premium in those sectors, whereas a country that is not will always trade at a discount.

India is often cited for the vigour and ambition of its image enhancing activities. Long prominent in tourism promotion, the country has more recently started to branch out into more general national image enhancement, and has had some notable successes in lobbying high-level decision makers – for example at the Davos forum in 2007, when India almost ‘stole the show’ with its ubiquitous self-promotion. Most of the big ‘branding stories’ of Asia are, however, associated with exports. The tale of how Japan built its economy and its image after 1945 is frequently cited as an export-led branding miracle, and several other countries – South Korea, Singapore, Malaysia, Taiwan and of course China itself – have quite deliberately set themselves the task of repeating the Japanese miracle. As all of these countries have discovered, this journey is a long one. To develop the capacity to produce world-class consumer goods, to distribute them worldwide, to market them and to build the customer service capability behind them that today’s consumers demand, is a decades-long task; and even once the industries are built and the products selling well around the world, an enhanced national reputation is depressingly slow to follow. Countries like Korea and Taiwan are disappointed to discover that, despite the huge successes of several of their manufacturers in other countries, and the major contribution such exporters have made to their economies, they are still not yet widely associated as a powerful country of origin for such goods.

If ‘nation branding’ is still in its infancy in Asia, the sister field of public diplomacy is equally so. The literature of public diplomacy is poor in Asian examples, and not all Asian ministries of foreign affairs even recognize the existence of such a discipline: Japan is a notable exception, and China – alongside its highly visible expansion into consumer markets overseas and its ever increasing investment in tourism promotion – has made major advances in cultural diplomacy through the expansion of its Confucius Institutes around the world. Yet the region is hardly short of countries that would amply reward some analysis of their situations through the lens of public diplomacy – the impact of the Borat movie on Kazakhstan’s image, the pariah status of Burma and North Korea, the way the relationship between Taiwan and the People’s Republic of China is played out in the public sphere, and so forth.

China

China

China’s international image continues to slide quite rapidly downhill: exactly the opposite of what China’s leadership was hoping for in the buildup to the all-important Beijing Olympics. Almost all of the ground its image had gained during the highly disciplined and stage-managed Olympics, plus some international sympathy as a result of a bad earthquake, was virtually wiped out as a result of a bad poisoning episode from baby milk, and the botched attempt to cover it up. It remains to be seen whether China’s still relatively strong economic growth, as other major economies falter, will help to achieve what such ‘nation branding’ initiatives have so far failed to do, and persuade the world that China is a country to be trusted, and admired.

Repeated episodes relating to dodgy products made in China further damage the image of the country, and, as long as they continue, will significantly slow down the process of taking the ‘Made in China’ brand from merely ubiquitous to actually trusted, and ultimately desired. I once predicted that within ten years’ time, we would start to see American and European products being launched on the marketplace with fake Chinese-sounding names in an attempt to make them appear more desirable than their real country of origin would allow: but this goal – which, let us not forget, Japan managed to achieve in just a few decades – looks further off than ever.

The Chinese leadership is frantic to create a better ‘soft power’ image for China in its potential marketplaces around the world, and the huge investment in Confucius Centres, the Beijing Olympics, the Shanghai Expo, its increasing aid donations in Africa, the more moderate and collaborative foreign policy in some areas, the acquisition of trusted Western brands by Chinese companies, are all part of this strategy. In a speech to the 17th Party Congress, President Hu Jintao (Editor’s Note: at the time when the book was being written he still held this position) spoke again of his aim to create trusted Chinese export brands – echoing the same promise made several years ago by the then Vice-Premier Wu Bangguo, as I reported in my 2003 book Brand New Justice – but this ambitious and complex manoeuvre is proving exceedingly hard to stage-manage on China’s own terms.

Part of the problem is that China is a bull in the global china shop, and is becoming simply too powerful to be able to carry out the delicate manipulations necessary to build a positive and trusted image in other countries. Take the news in late 2008 that the Chinese oil firm PetroChina trumped US rival ExxonMobil to become the world’s biggest firm, with a market capitalization of a trillion dollars: no matter how you tell a story like this, the reaction of many ordinary people is more likely to be fear than liking or respect.

Brand China is going from invisible to overbearing in one leap. At least the United States enjoyed a couple of centuries of admiration and affection before starting to experience the downside of its success in the global marketplace.

Brand China is going from invisible to overbearing in one leap. At least the United States enjoyed a couple of centuries of admiration and affection before starting to experience the downside of its success in the global marketplace.

As I pointed out in Brand America, America’s image problems have at least as much to do with its achievement of many of its economic aims as its frequently unpopular foreign policy: the world loves and supports a challenger, but let it succeed in its challenge and acquire the power it seeks, and the love will quickly turn to fear, and the fear to hatred. China is getting there in one short step.

China has the economic and increasingly the political strength to do pretty much whatever it wants: but the one thing it cannot do with all that power is to make itself much liked. And as its leadership has clearly understood, being liked is the fundamental prerequisite for building modern, market-based Empires on the US model.

The results from the Nation Brands Index do not make comfortable reading for China. If we compare the NBI results for the 35 countries in the survey over the period between its first appearance in the Index in early 2005 and 2007, China experienced the worst trend of any country measured in the survey. Its overall score declined during this period by four percent. This may not seem much, but it is nearly double the ground lost by any other country in the NBI – and around six percent below the fastest improving countries like the Czech Republic and Brazil.

What is worse for China is that the decline is much greater than average in areas where it most needs traction in the international economic arena. The worst figures are in the Immigration and Investment dimension and in particular for people’s willingness to live and work in China – the ‘talent magnet’ question. For Immigration and Investment as a whole, China’s score declined by 11.4% between the final quarter of 2005 and the second quarter of 2007. For willingness to live and work in China, the figure was nearly 14%. This compares with drops of around 9% for Russia and Indonesia, the countries with the next most negative trends in this area. Only Israel is now less popular than China as a place to live and work.

What is worse for China is that the decline is much greater than average in areas where it most needs traction in the international economic arena. The worst figures are in the Immigration and Investment dimension and in particular for people’s willingness to live and work in China – the ‘talent magnet’ question. For Immigration and Investment as a whole, China’s score declined by 11.4% between the final quarter of 2005 and the second quarter of 2007. For willingness to live and work in China, the figure was nearly 14%. This compares with drops of around 9% for Russia and Indonesia, the countries with the next most negative trends in this area. Only Israel is now less popular than China as a place to live and work.

China’s bad news is not confined to the Immigration and Investment dimension; for the country of origin effect on product purchase, the results were not good. If people find out that a product is made in China, the majority of people in the survey said they would be less inclined to buy it. What’s more, the people who said they had bought products from China were even more negative than the respondents as a whole.

The trend for China’s products was also the worst of any of the 35 countries. In the 2008 study, China is now 47th (the third-lowest country) for products, compared with 24th in late 2005. Its score declined by nearly six percent over the ’05–’07 period, compared for example with an increase of nearly six percent for Brazil, another of the quartet of largest emerging markets.

If China is hoping to emulate or even outstrip Japan’s remarkable 40-year rise as a leading global producer of trusted and desirable consumer products, it appears to have taken a wrong turn in the road. The first stage of this process – familiarity with the ‘Made in China’ label through wide distribution of its products – has been achieved with remarkable speed and efficiency, but the second stage – where familiarity turns to trust – looks considerably more elusive. China’s current highly publicized quality issues have certainly delayed this stage. The final stage – where trust turns to desire and premium positioning – can only take place when the corporations as well as the products are truly world class, and can design and brand to world-class standards, and this stage looks to be decades away for the majority of Chinese products. There are exceptions – Haier and Lenovo being perhaps the most high-profile examples – and of course there is always the option of ‘fast-tracking’ the process through the acquisition of already trusted foreign brands, an approach which both China and India see as part of their strategy.

China’s tourism appeal is lagging too. People are showing no increase in their desire to visit China, despite the undoubted fascination of its historical heritage. In fact the trend in China’s results for ‘likely to visit, money no object’ is the worst of any country – a drop of 5.6% since late 2005. China is now down in 21st position in the tourism brand rank, according to the 2008 study.

None of this augurs well for China and its attempts to promote itself as an attractive and trusted member of the international community. China’s recent growth may have been stellar, but sooner or later it will have to base its economy on the sound footing of a comprehensive, robust and improving national reputation.

This must include a governmental system that people trust. How far people’s perceptions of China’s governance spill over into these other areas, we cannot say for sure. China showed one of the worst results for governance in the 2008 survey, outranking only Nigeria and Iran, and this included its results for competence in domestic governance. It is highly likely that if people have little confidence in a country’s ability to manage itself, they will not be willing to invest their time and money in it, and a successful Olympic Games will certainly not have been sufficient to achieve the image turnaround they are hoping for.

Building a reputation, as China will discover, often feels like taking two steps forward and one step back: no sooner have you achieved something that makes people feel good about you, than it’s forgotten. Governments must plan for the long term, and obsessively ask: ‘what can we do next?’ A successful Olympics is the start of the process, not the end; and of course it takes more than sporting events to build a national image: policy, products, people, culture, tourism and business have to work together to earn the country a better reputation. Only real changes, sustained over the very long term, can turn around a national image – especially one as bad as China’s.

Yet it’s not an impossible task: Japan and Germany both suffered from worse images than China’s half a century ago, and are now amongst the most admired nations on earth. If any country has the patience and the resources to imitate those examples, it is surely China.

Yet it’s not an impossible task: Japan and Germany both suffered from worse images than China’s half a century ago, and are now amongst the most admired nations on earth. If any country has the patience and the resources to imitate those examples, it is surely China.

China, like India and indeed many countries in Asia, has for many centuries held a strong fascination over the imaginations of people in the West, and this glamour is an important component of their ‘brand equity’ in the age of globalization. But exoticism is a double-edged sword, and whilst such an image may support the tourism industry to a degree, and perhaps certain export sectors – Chinese tea, Indian perfume, Japanese fashion – it can prove rather unhelpful for a country that is trying to build its reputation in financial services, engineering or technology. India’s image is currently straddling these two sides of its image in a way which at times seems almost uncomfortable: a fundamental component of its tourism and cultural image, for example, is its poverty, and yet its more modern commercial image is an image of wealth. By the same token, the ‘destination brand’ of India is an image of chaos, almost of anarchy – hardly a useful attribute when one is trying to build a service economy based on efficient customer service or reliable motor vehicles.

This is, without question, an interesting stage in the maturity of the West’s perception of the East. The facile and comforting clichés of ‘the mysterious Orient’ are the legacy of a less connected, less tolerant and more ignorant age, where engagement with other civilizations was limited to imperial adventures rather than true collaboration in a global marketplace. The demystification of the Orient is a necessary phase in human development, which implies major shifts in the reputational capital of the world.

Very few countries, in fact, have images that remain entirely consistent between East and West. South Korea is a classic case of a country that enjoys a rather positive reputation in its own ‘neighbourhood’ – the ‘Korean wave’ of commercial entertainment has made Korea something of a celebrity in East and even South Asia, but the wave doesn’t reach Europe or the Americas, where – at least according to the Nation Brands Index – there appears to be substantial confusion between South Korea and its northern neighbour (to the obvious disadvantage of the South).

Most of the ‘Asian Tiger’ economies of East Asia are generally admired in Europe, yet there is a strong prejudice against them amongst South American populations, and especially in Brazil. The Brazilians show a remarkable distaste for most Far Eastern countries which is entirely out of kilter with ‘global’ views. One can only surmise what this antipathy stems from, but it does suggest that the world is still very far from united in a common sense of national reputation and image.

Most of the ‘Asian Tiger’ economies of East Asia are generally admired in Europe, yet there is a strong prejudice against them amongst South American populations, and especially in Brazil. The Brazilians show a remarkable distaste for most Far Eastern countries which is entirely out of kilter with ‘global’ views. One can only surmise what this antipathy stems from, but it does suggest that the world is still very far from united in a common sense of national reputation and image.

Democracy and place image do not always go easily or simply together, and it is noticeable that two of the places most widely recognized for the grip they have managed to exert over their international reputations – Dubai and Singapore – are both places that are run on somewhat corporate lines. This is surely no accident: the main reason why building a brand in the corporate sector is so much more straightforward than doing the same for a place is precisely because corporations have a supreme commander in the shape of their CEO, whose vision tends to form the defining narrative of the place, and deviation from this narrative often results in dismissal. Whatever one might say about North Korea, one has to admit that its brand is clear, simple and consistent – again, the consequence of the entire society being run along the lines of one man’s viewpoint.

It remains to be seen whether India, the world’s largest democracy, or China, the world’s fastest-developing economy and the last major bastion of Communism, will eventually prove more successful at managing their reputations in the eyes of the world. So far, it looks very much as if democracy is winning the day, but the determination, resources and skill of the Chinese should never be underestimated.