An Overcrowded India

Evgeniy Pakhomov

Modern day India faces major economic and social problems as a result of a seemingly unstoppable overpopulation problem. The Indian government’s hasty, and at times violent, attempts to limit the birth rate has forced it to adopt a different approach; it has now moved on to a policy of persuasion and ‘small steps’ tactics.

At first glance, India’s sizeable population might appear enviable. The country boasts nearly 1.3 billion inhabitants, which means that one in six people live in what is now the world’s largest democracy. Even better, young people under 35 make up the greatest percentage of the country’s population. But any visitor to India will see that this translates to an endless stream of people in the streets and huge crowds at political rallies and religious celebrations. Considering that medium-range forecasts place the country’s average demographic growth between 1.3% and 1.6%, India is on track to become the most populous country in the world by 2030, leaving its main regional rival, China, far behind.

India is not particularly optimistic about this prospect. Overpopulation has long been a serious issue, and many believe that a great deal of India’s current challenges are due to the fact that they simply have too many inhabitants. It is hard to believe now that India’s population was barely 350 million when it gained its independence in 1947. Today, a large portion of India’s economic growth is ‘eaten up’ by the incessant population growth – the rapidly expanding economy is unable to keep up with an even faster growing populace.

Specialists believe that there are several reasons behind Indian society’s high fertility rate. The strong local traditions are one of them. Marriage and childbirth form an important part of ‘sanskara,’ or life cycles, that a typical Hindu goes through. There is a high number of early marriages, especially among young women. Even though the legal marriageable age is 18, nearly half of Indian women marry much earlier, something that society tends to turn a blind eye to. As a result, many young women give birth to their first child before reaching adulthood.

Traditionally, a family’s wealth is measured by its livestock and male children – Indians have prayed to their gods for an abundance of both from time immemorial. Moreover, less well-to-do families, especially in rural areas, often view women as a source of labor, whereas children (and boys in particular) are regarded as future breadwinners who will take care of their elderly parents. “The problem lies in the patriarchal family system. Women are expected to follow traditional values, rules, and social norms in every aspect of their lives. That is why traditional families pay no heed to the calls to limit the birth rate,” explains Sai Karan, a women’s activist in Mumbai, in an interview with BRICS Business Magazine.

The fact that male children are perceived as the main source of wealth causes another unexpected yet serious problem. Traditional families consider it a bad omen if the firstborn child is a girl. As a result, female infanticide (and often termination of female fetuses) has reached epidemic proportions. In the mid-1970s, the government even had to pass a law banning doctors from revealing the gender of the fetus during ultrasound. Still, the country loses up to 600,000 baby girls annually. Billboards and films often discourage female abortions – in TV ads and Bollywood films, daughters are often portrayed as integral parts of a happy family – but these measures do not seem to have helped.

As a result, India faces a serious gender imbalance – there are only 940 women per 1,000 men. This means that the percentage of single males is constantly on the rise in a steadily growing populace. This ‘shortage’ of women has yet another unexpected consequence. Experts agree that this demographic shift explains a wave of sexual violence that has engulfed India in recent years.

Overpopulation is also believed to be the cause of India’s pervasive illiteracy. In a number of districts in India, those who are merely able to sign their pay slip are considered literate. Many Indians, especially those coming from poorer and uneducated families, can barely read and write. Needless to say, they know very little about modern birth control methods.

However, employment seems to be the most pressing problem. Even though the official unemployment rate is only 4%, this figure is just the tip of the iceberg. In reality, hidden unemployment remains much higher, especially in rural areas.

In addition, the rapidly growing population needs more and more living space, resources, and infrastructure. New hospitals and schools are being built in India, but they are still in short supply. “Classes of 80 and even 100 students are a common occurrence in Indian schools. You can hardly learn anything in such an environment. Look at any train station in India or any market – there are huge crowds everywhere,” says Bhanu Pandey, an Indian journalist, in an interview with BRICS Business Magazine.

Finally, the volatile demographic situation puts more and more pressure on the country’s natural resources. Today, India is faced with an acute shortage of arable land and drinking water. Entire forests have been cut down and rivers have been polluted in the name of freeing up more land, which impacts the country’s environment, the state of which was far from perfect to begin with. In the Environmental Performance Index, developed by the Yale Center for Environmental Law & Policy and Columbia University in collaboration with the World Economic Forum (WEF), India was ranked 155th, putting it much lower than its BRICS partners.

Everything for Mother India!

Even the founding fathers of independent India were aware of the overpopulation problem. In the early 1950s, India was the first country in the world to officially adopt a family planning program. Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru was convinced that the only way to catch up with the standard of living and level of economy of the developed nations was to slow his country’s unbridled birth rate.

At that time, the government placed greater emphasis on ‘propaganda and raising awareness.’ Clinics were mandated to provide advice on family planning to anyone who required it, and citizens of the newly independent country were expected to show a keen interest in modern birth control methods. The popular, and then ubiquitous, slogan ‘Hum do, hamare do’ (We two, our two) was coined around the same time.

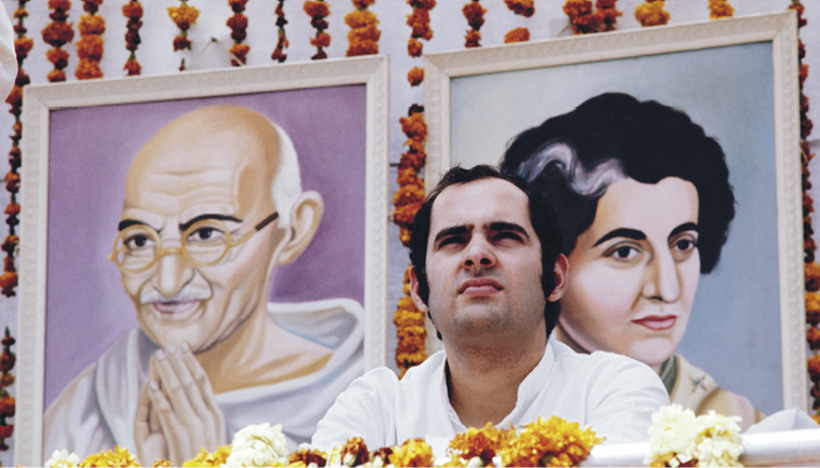

Sanjay Gandhi. On the poster: Mahatma Gandhi and Indira Gandhi

In the early 1950s, India was the first country in the world to officially adopt a family planning program. Jawaharlal Nehru was convinced that the only way to catch up with the standard of living and level of economy of the developed nations was to slow his country’s unbridled birth rate

A married couple with two children was perceived as the perfect family. It is certainly no coincidence that in the 1950s and 1960s, during the ‘Golden Age of Bollywood,’ all of the ‘good guys’ were from families like these. Poets who promoted this lifestyle in newspapers would also come up with similar slogans: ‘One for me and one more for you, and every day brings new happiness!’

Alas, their aspirations never materialized. Instead of going down, the birth rate went up. In just 10 years, starting in 1951, India’s population grew from 361 million to 439 million. It turned out that even though Indian audiences did enjoy a good Bollywood ending, they were not too eager to rush to family planning centers. Tradition was not the only reason for this failure, and not by a long shot. Major religious leaders of all denominations – Hindu, Muslim, and Buddhist – spoke out strongly against attempts to regulate the birth rate.

It was clear that different measures would be required. The authorities turned from propaganda to healthcare – they launched a voluntary sterilization campaign accompanied by a widespread promotion of contraceptive coils. Entire camps were deployed around the country where both men and women could undergo sterilization.

The government-sponsored campaign reached its peak in 1975-1977 when the country declared a state of emergency. Against the backdrop of heavy frustration over the economic and social policies of Indira Ghandi’s government, unprecedented measures were taken to strengthen the regime in power. Opposition organizations were banned, media censorship was introduced, and certain rights protected by the constitution were abolished. The government badly needed some degree of economic success. The struggling government bet heavily on radical measures to cut the birth rate, this time more brutal than ever before. Indira Ghandi’s youngest son and political heir apparent, Sanjay Gandhi, was put in charge of this campaign. His actions were decisive and at times bordered on the unlawful. One of the measures he introduced was to sterilize men. “There was a certain rationale behind it. Often times for a traditional Indian male, it is easier to go to the doctor than to let a stranger handle his wife,” Pandey explains.

Those who voluntarily agreed to undergo vasectomy were promised money and loans, while the procedure itself was performed free of charge. The campaign was backed by massive propaganda – elderly public servants having undergone the procedure were filmed leaving the doctor’s office proclaiming passionately,

“I did it for you Mother India!”

However, the voluntary spirit was soon forgotten. The police would pick up the poor, mostly from the lower castes, including the untouchables and criminal offenders, and force them to undergo the procedure. Human rights activists believe that during this short state of emergency, 6.2 million men, mostly the poor, were affected by this ‘ugly sterilization campaign.’

However, even these measures failed to halt the explosive population growth and there was substantial backlash against the government. A wave of mass protests and demonstrations engulfed the entire country. One of the most popular slogans the protesters chanted was, “Save India, save our penises!” In March 1977, the Indian National Congress (INC) – the ruling party – lost the parliamentary elections in a landslide, and ceded power to the competition for the first time in the country’s history.

Free of Charge and Down the Drain

The authorities in India learned their lesson. They realized that the birth rate issue could not be resolved by resorting to aggressive measures and the use of force. Since then, the family planning program has been placing greater emphasis on education and voluntary participation. “One of its main objectives is to ensure universal access to birth control and to explain how to use various methods,” said Pandey. “In India, even prostitutes receive free condoms from humanitarian organizations. This is believed to also be a part of the campaign to combat the high birth rate.”

This paradigm shift was not coincidental. It became clear from the very outset that simply distributing free birth control would not be successful. The poor masses did not know how to use contraceptives, and far from the majority were capable of reading the instructions on the package. Today, a network of seven family planning centers has been established in India offering information about what needs to be done and how, and performing sterilization procedures where necessary.

In addition, Indian authorities insist on mandatory registration of all marriages and births, in an attempt to eradicate underage marriage, which remains a serious problem in many rural areas, as well as to reduce child mortality. As contradictory as it sounds, this measure is equally important in reducing the birth rate – after all, poor families tend to want to have as many children as possible because it is unlikely they will all survive.

Scandals relating to the sterilization campaign still continue to plague India to this day. For instance, in early November there were reports of 12 patients dying at a ‘sterilization camp’ in the state of Chhattisgarh. All of them volunteered to undergo the procedure, tempted by financial rewards (according to various sources, the payments ranged from $20 to $25). However, the doctors used the wrong tools and medications, and the surgery went horribly awry.

At the same time, some human rights activists claim that medical workers at family planning centers often pressure their female patients to opt for surgery. Reportedly, in the last three years, 336 patients have been killed because of the poor skills of operating surgeons. One can only guess how many women have been left with long-term health problems as a result of these botched surgeries. According to the local press, around 4 million sterilization operations have been performed in the last two years.

Still, the Indian government’s efforts to limit the birth rate have borne some fruit. According to experts, the number of married women who regularly use contraceptives has gone up from 13% in 1970 to 48% in 2009, reaching 50% today. The birth rate, measured as the average annual number of births per 1,000 persons, has gone down from 24.9 in 2000 to 20.2 in 2013.

Yet this hardly means that the trend has been reversed. Preliminary estimates indicate that India’s population will not stop growing until 2050 at the earliest, when the number of births and deaths is likely to level off. However, by that time, the country’s population will have reached at least 1.6 billion.

If these estimates prove accurate, nearly 500 people will have to share each square kilometer of Indian soil. Maintaining social peace in an environment like that would be a tall order, and would require India to accelerate its economic growth in the near future. According to Ranjit Goswami, from the Institute of Management Technology in Nagpur, at least 100 million new jobs would have to be created every 10 years to achieve that goal.

The mood in India clearly indicates that people expect change. “This is also illustrated by the results of our recent elections – India’s population voted for new politicians,” said Felix Yurlov, from the Institute of Oriental Studies at the Russian Academy of Sciences. “In the meantime, one should abandon the idea that demographic issues can be resolved by a number of short-term measures. What the country needs is modernization and not sterilization. It needs long-term, well thought-out policies that also take into account factors such as education, employment, and the role of women.”

However, the main difficulty is that in trying to get traction, New Delhi seems to be running out of time. It is entirely possible that in a few decades, the entire world will have to deal with India’s overpopulation, just as it is addressing the issues of pandemics and arms races today.