BRICS Education in the Global Race

Jim O’Neill, former chairman of Goldman Sachs Asset Management, coined the BRIC acronym in 2001, predicting that the BRICs would overtake the six largest western economies by 2041. But any economic growth has to be supplemented with the ability of a population to gain knowledge and qualifications. The annual QS World University Rankings assess universities worldwide; Jane Playdon looks at where the BRICS fit in.

Last November, Christian Déséglise, co-director of Columbia University’s BRICLab and an adjunct professor of international and public affairs, spoke of the rapid growth of the BRIC nations at a conference called BRICs: The Quest for Global Growth. Déséglise said the BRICs have contributed 31% to global nominal growth since 2001, almost double their contribution of 17% in the previous decade, and, since 2008, that contribution has been 55%.

But, according to fellow co-director Marcos Troyjo, that change has been driven by comparative advantages, and will need to be based on more competitive advantages in the future.

Defining competitive advantage

The World Economic Forum (WEF) defines competitiveness as “the set of institutions, policies, and factors that determine the level of productivity of a country,” which in turn determines the level of prosperity an economy can reach. To compile its Global Competitiveness Index (GCI), the WEF looks at many components, grouped into 12 “pillars of competitiveness,” of which higher education and training is the fifth.

The pillars are interconnected, with a negative performance in one area affecting the others. But the weighting of each one depends on a country’s stage of economic development. Although the BRICS countries (that is, including South Africa) are grouped together in terms of being high-growth economies that could change the economic and trade landscape in the future, the WEF Global Competiveness Report 2013–2014 puts them at different stages: Brazil and Russia are in transition to the third, most-advanced, stage – an innovation-driven economy; China and South Africa are in the second stage – an efficiency-driven economy; and India is placed in the first stage – a factor-driven economy where competitiveness is based on basic requirements.

The pillars are interconnected, with a negative performance in one area affecting the others. But the weighting of each one depends on a country’s stage of economic development. Although the BRICS countries (that is, including South Africa) are grouped together in terms of being high-growth economies that could change the economic and trade landscape in the future, the WEF Global Competiveness Report 2013–2014 puts them at different stages: Brazil and Russia are in transition to the third, most-advanced, stage – an innovation-driven economy; China and South Africa are in the second stage – an efficiency-driven economy; and India is placed in the first stage – a factor-driven economy where competitiveness is based on basic requirements.

In the GCI, higher education and training is weighted higher in efficiency- and innovation-driven economies, with an emphasis in innovation-driven economies on research and development, and collaboration between universities and industry.

The Russian Federation scores the highest amongst the BRICS countries for higher education and training, ranking 47th out of all 148 countries for this ‘pillar.’ China comes next, ranking 70th, then Brazil in 72nd place, South Africa (89th) and India (91st).

So to what extent is this connection between higher education and economic advancement reflected in the QS World University Rankings for 2013–2014? Here we take a look at the latest data, reflecting on the BRICS countries’ progress in this area.

BRICS performance

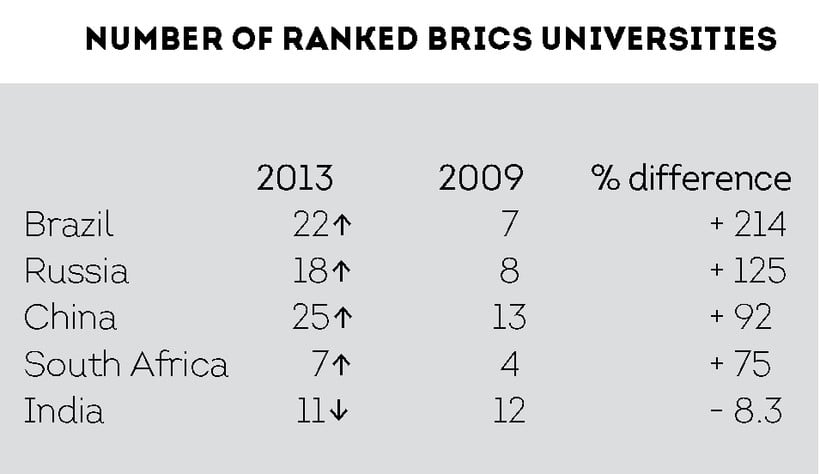

The QS World University Rankings now cover 800 institutions around the world, with an extra 100 added since the last edition. Brazil and Russia – countries transitioning from efficiency- to innovation-driven economies according to the WEF – rank within the world top ten for number of new institutions added this year. Brazil added ten, putting it in third place for number of new institutions ranked, and Russia added four, making it ninth for number of newcomers. China and South Africa both added two institutions to the rankings this year, while India’s number was unchanged from 2012.

QS measures universities’ performance in four key areas: research, employability, teaching, and internationalization. These are assessed on the following indicators: academic reputation, employer reputation, faculty-to-student ratio, citations per faculty, ratio of international faculty to overall numbers, and ratio of international students to overall numbers.

Academic and employer reputations are establi-shed using the results of worldwide surveys of acade-mics and employers. This year 62,094 academics gave their opinions on the institutions producing the best research in their field, and 27,957 employers identified the universities they believe produce the best graduates. Zoya Zaitseva, Regional Director for Eastern Europe and Central Asia at QS, says that these are the indicators BRICS universities should focus on, and try to improve recognition through the number of experts familiar with their national higher education systems. At the moment, the majority of answers collected are still coming from the U.S. and Western Europe.

In the latest QS World University Rankings, Russia and India each have five universities ranked within the world’s top 400; Brazil and South Africa each have three, and China has 11. China firmly leads with seven institutions in the BRICS top ten, which also has one each from Brazil, Russia and South Africa.

Leaders in each sector

Chinese institutions also retain the strongest academic and employer reputation scores among the BRICS, ranking from 19th to 600th in these indicators, but with the majority of institutions declining since last year.

Russian universities score reasonably well for academic and employer reputation, with rankings on these indicators ranging from 83rd to 800th, and the country’s top four institutions all showing an improvement since last year in terms of academic reputation.

Brazilian universities rank from 51st to 800th for academic and employer reputation, with the majority of figures showing an improvement. Indian institutions rank from 75th to 700th for academic and employer reputation, with most weakening in this area since last year. South Africa, on the other hand, shows improvement in academic reputation amongst all its ranking institutions this year, but a decline in employer reputation, with rankings across both areas ranging from 142nd to 650th.

While Russia’s ranking institutions have gene-rally good scores for academic and employer reputation, their strongest scores are in fact for faculty-to-student ratio – the number of academic staff employed per student enrolled – with the majority ranking within the world’s top 200 on this indicator. While faculty-to-student ratio is not a definitive method of establishing teaching quality, a high score on this indicator does suggest a good degree of individual supervision, indicating a strong commitment to teaching.

Russia’s high scores for this indicator come despite the fact that, according to the latest figures from the OECD, the country’s expenditure per tertiary student was $7,039 in 2010, well below the OECD average of $13,528. However, the OECD data also show that Russian expenditure on tertiary education in that year was 1.6% of GDP, on a par with the average for OECD member countries, many of which are innovation-driven economies.

Three Brazilian institutions score within the top 200 for faculty-to-student ratio, but half of the ranking Brazilian institutions are outside of the top 400 in this area, with many of those numbers deteriorating since last year. India and South Africa have no institutions currently ranking in the top 400 for faculty-to-student ratio, and both countries’ scores in this indicator have deteriorated since last year. China has five in the top 200 and 11 ranking outside the top 400, again with the majority of the numbers getting worse since last year.

Another area where Russia and South Africa show strength is in numbers of foreign students. Out of all the BRICS, only these two countries have rankings inside the world’s top 400 for the international students indicator. This is consistent with OECD figures that say the number of foreign students enrolled in Russian institutions increased by 90% between 2005 and 2011. However, only three out of 18 of Russia’s ranked universities have improved their international student ratio scores this year, with the rest all decreasing. Meanwhile none of the ranked South African institutions improved their international student ratio scores this year.

Another area where Russia and South Africa show strength is in numbers of foreign students. Out of all the BRICS, only these two countries have rankings inside the world’s top 400 for the international students indicator. This is consistent with OECD figures that say the number of foreign students enrolled in Russian institutions increased by 90% between 2005 and 2011. However, only three out of 18 of Russia’s ranked universities have improved their international student ratio scores this year, with the rest all decreasing. Meanwhile none of the ranked South African institutions improved their international student ratio scores this year.

Russia also has the highest percent of tertiary enrollment in the BRICS, which according to the WEF Global Competiveness Report 2013–2014 was 75.9% of the population last year, ranking it 14th in the world. This is in comparison with Brazil’s 25.6%, China’s 26.8%, India’s 17.9% and South Africa’s 15.4%. And, according to the OECD, in 2011 the percentage of Russians that had attained tertiary education was 53% – well above the OECD average of 31%.

In terms of citations per faculty, a measure of research impact, all the BRICS except for India showed a general decline in this area. China’s top seven institutions did well, but the rest all deteriorated.

The QS World University Rankings reveal different strengths and weaknesses in the higher education systems of the BRICS countries. Brazil, China and South Africa do well for academic reputation; Brazil and China for employer reputation; India for citations per faculty; and Russia for faculty-to-student ratio and international students. But internationalization in general is a key area in need of improvement across all these countries.

Jane Playdon is Education Writer for TopUniversities.com

To see the latest QS World

University Rankings in full, visit

topuniversities.com/Rankings