“They Said Poverty Would Always Be with Us. Well Maybe Not”

Daniel Howden

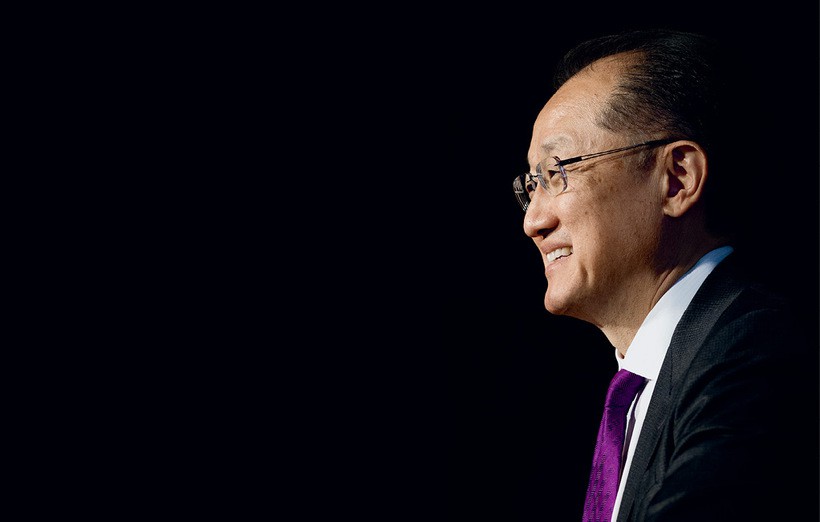

It is an unlikely mode for a saviour: middle-aged, suited and bespectacled, staring out from a billboard erected over the warren of slums that surround Kinshasa, the chaotic capital of the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). The face is that of Jim Yong Kim, the first man from outside the discipline of economics to take the helm at the World Bank, an institution many observers have accused of lacking purpose.

Having just celebrated his first year in charge, the Korean-American medical expert has refocused the world’s premier development bank on ending extreme poverty. Africa’s fastest-growing mega-city, which has no shortage of poverty, is an apt place to assess how he has set about curing the malaise at the bank and how he intends to deepen its impact.

Mr Kim and his fellow Korean and United Nations Secretary-General, Ban Ki-moon, were in Congo to commit development dollars to the high-level diplomacy it is hoped can turn around one of the world’s worst-performing countries. Mr Kim announced $1 billion in support of the regional peace process, much of it to be sunk into hydropower schemes, road-building and boosting cross-border trade. These are the kind of big numbers he is interested in, in pursuit of big goals.

“I want to be of use and try to have a transformational impact,” he said. He wants the major agencies to “get together and focus on a topic, ask what are the obstacles and how do we remove them.”

Less than 12 months are left to reach the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), ambitious anti-poverty targets set for 2015 by the UN. While the DRC, which languishes at the bottom of human development indices, represents part of the failure of those targets, the World Bank leader prefers to dwell on the positives. Global poverty, defined by the bank as living on $1.25 or less per day, was halved five years ahead of schedule. The next phase is to lift the remaining 20% of the world’s population out of extreme poverty by 2030.

“The efforts to end poverty have been really significant,” says Mr Kim. “They said poverty would always be with us. Well, maybe not.”

A proportion of people – he estimates three per cent – will remain below the poverty line due to natural disasters and their related aftermaths, but otherwise “extreme poverty will be gone from the earth.” It’s the kind of sweeping statement that is familiar to a world audience. His entourage wear “end poverty” badges on their suit lapels.

While poverty has been halved, it is questionable how much the aid money and the MDGs contributed beyond helping to measure it. Most of those who rose out of poverty did so in places like China and Brazil on the back of economic growth.

Ambition and targets have been the signature of the 58-year-old’s unusual career. During the 1980s and 1990s, as one of the founders of the Partners in Health, a community-based health organisation in Haiti, he took on the World Health Organisation (WHO) over the treatment of drug-resistant tuberculosis which was deemed to be too expensive to work in poorer countries. The group’s success in lowering the cost of treating the disease in Haiti, and later Peru, persuaded the WHO that it could afford to change its approach. In fact, he won the argument so convincingly the WHO decided to hire him to run its HIV-Aids programme in 2003. He started targeting the treatment of three million infected patients in the developing world within the first two years. That target was missed, at least until 2007, but the drive to get there is credited with turning the tide globally on HIV-Aids.

He was introduced as a “visionary” when he was unveiled as the new president of Dartmouth College, a bastion of America’s Ivy League, in 2009. His friend and co-founder at Partners in Health, Paul Farmer, told students and faculty that their new leader’s capacity to look into the future was akin to that of the Oracle in the popular science fiction film The Matrix.

Yet his appointment to the World Bank last year was not universally welcomed. Many observers resented his imposition by the United States over popular candidates from Africa and Latin America, while others worried that he was not an economist. They pointed to his presence at protests against the World Bank in 1993. Mr Kim now says that it was the lender’s “one size fits all” approach to economies that he objected to.

“It was already a different World Bank when I walked in,” he says, crediting the popular James Wolfensohn, who left in 2005. But taking over the multilateral lender can be awkward. When George W. Bush appointed the conservative Paul Wolfowitz to replace Mr Wolfensohn, the bank was positively mutinous. He lasted two years amid a scandal over the promotion of his partner within the organisation.

Some insiders see Mr Kim in the same mould as the dynamic Mr Wolfensohn. Others portray him as distant and only “professionally charming.” Some have been unconvinced by the voluminous discussion of change. He has appointed a ‘vice president of change’ and ‘change teams’ to propose radical alterations to the bank’s modus operandi. Targets and measuring are again to the fore, what the institution’s headman calls “knowledge work.”

He was introduced as a “visionary” when he was unveiled as the new president of Dartmouth College, a bastion of America’s Ivy League, in 2009. His friend and co-founder at Partners in Health, Paul Farmer, told students and faculty that their new leader’s capacity to look into the future was akin to that of the Oracle in the popular science fiction film The Matrix

As well as aiming to end poverty, the bank has set itself the task of tracking the progress of the bottom 40% in every country as a means of measuring social mobility and equality.

Mr Kim’s critics on the left attack him for an over-emphasis on economic growth, and accuse him of not doing enough to combat inequality. Those on the right are concerned that his ‘anti-growth’ views will come to the fore. They fret he will succumb to pressure from China to water down the bank’s Doing Business report – an annual league table that nudges reluctant nations in the direction of reform – which has embarrassed Beijing over corruption and red tape.

Both clans may overestimate the influence of the bank. As Mr Kim points out, overseas development assistance (ODA) has shrunk for the last two years in a row and now stands at $125 billion.

“That sounds like a lot but if you look at the infrastructure needs of India they are $1 trillion alone,” he says. “All the organisations who benefit from ODA should be humble. Let’s be as thoughtful as possible about these expenditures and talk with governments and use private sector investment.”

Since the end of the Second World War the number of international institutions has exploded and while many have noble goals they are also prone to egos, rivalries, waste and duplication. The bank president is content to play a supporting role to Mr Ban, with whom he shares a rapport.

This level of co-operation between large international institutions is not the norm. None of the vast entourage who travelled with their Korean leaders could recall anything similar to their Africa trip. Squabbles broke out over everything from seating plans to numbers in the respective delegations.

As a veteran of the multilateral system the best he could say about co-operation between big organisations was that “sometimes they didn’t hate each other.” On his way up, Mr Kim admits to encountering “egos at the top and egos all the way down.” It is the observation of an outsider, a viewpoint he has maintained despite his journey to the heart of the establishment.