How to Beat China in China

Phil Leung, Weiwen Han and Raymond Tsang

French appliance manufacturer Groupe SEB and Danish brewer Carlsberg sell in vastly different industries, but they both had similar experiences trying to get ahead in the treasure chest that is China. In 2002, Groupe SEB was inching forward – growing by, at most, 0.2% a year – and it was the 32nd-ranked company in its segment in China. Carlsberg was also at the bottom of the pack, a small player with less than 1% market share, with no clear path to a sustainable position. Then both companies got serious. In 2006, Groupe SEB started buying shares in China’s leading appliance manufacturer, Supor, a move that steadily and dramatically increased its market share. The company leapfrogged to 5th place by 2010. For its part, Carlsberg started acquiring or partnering with Chinese local breweries. The brewer has watched inorganic volume grow at a compound rate of 43%, and achieved organic growth of 31% from 2002 to 2011 when, according to Euromonitor, it became China’s 10th-ranked brewer, with a focus on Western China, where it is the market leader.

China is as challenging to global companies as it is important. Even when the economy cools down, it is creating opportunities for scale that are unmatched anywhere else. Already it is the number one market in a host of industries, including automobiles, home appliances, and mobile phones. It is also emerging as a leading profitable growth engine for multinational companies (MNCs). In a recent American Chamber of Commerce in China survey, 68% of MNCs are reaping margins in China that are comparable with or higher than worldwide margins.

But as Groupe SEB, Carlsberg, and countless other companies have learned, winning by going it alone is not easy. The competition has never been tougher, as a new generation of domestic companies – local champions – is quickly setting the standard for low-cost ‘good-enough’ products. MNCs need to measure up or they will fall behind. And with so much competitive pressure, they need to do it fast.

Chinese players are showing how easy it is to outpace MNCs. In consumer goods, local company Hosa overcame Italy’s Arena to become the number one seller of swimwear by targeting the mass market. In healthcare, domestic ultrasound manufacturer Mindray became the number one player by using technology that was reliable but less advanced, and by offering 30% to 40% lower prices than similar models from MNCs.

Mergers and acquisitions (M&As) and joint ventures (JVs) have always been options for success in China, and in restricted industries like banking or insurance, there is still no alternative. In those cases, deals not only allow a company to operate in China but may also give the MNC access to important government contracts. But the pace of deals has dramatically intensified outside of restricted industries. Every week seems to bring with it announcements of new joint ventures or merger deals. Only around 25% of Fortune 200 companies are relying on organic growth in China.

Increasingly, the deals are becoming transformative for the companies involved, providing upstream activities, research and development (R&D), intellectual property (IP) contributions, core capabilities sharing, and other means of advancing in China. In addition to the original intention of gaining regulatory access, MNCs are turning to inorganic growth to lower costs for both domestic production and exports, fill portfolio gaps, and strengthen their go-to-market capabilities – all areas in which domestic players typically have the edge.

Costs: feel the difference

Let us start with cost levels. It is no secret that local players benefit from less stringent specifications, cheaper raw materials,lower labor costs and lower back-office overhead costs. The difference in production costs in China is sometimes staggering. In both swimwear and carpets, for example, analysis shows that one local company’s unit costs for local production are 40% less than that of a leading MNC competitor’s production in China. In medical devices and cell phones, comparisons between a local player and an MNC show that costs are 20% less for the domestic company. It is virtually impossible to replicate a Chinese company’s cost structure. That is one of the major reasons why Japan’s Hitachi Ltd. has entered no fewer than 36 joint ventures, M&As or partnerships in China to piggyback off the low-cost manufacturing of partners like Haier and Shanghai Electric.

And consider Chinese companies’ go-to-market approaches. Unlike their multinational counterparts, domestic players typically have extensive built-in distribution networks, and they often focus their efforts on non-top-tier cities, where much of the growth is taking place. Of the ten toothpaste brands with the most penetration in Tier-2 cities, seven are local.

A local company may have a 5,000-member on-the-ground sales force in high-growth Tier-2 to Tier-5 cities, something that would take years for an MNC to replicate. Buying a Chinese company gives an MNC access to key channels and large accounts –increasingly critical for success in China. In addition, Chinese companies often have a low-cost distribution network, which is particularly important for good-enough or mid-market products, where distribution has a higher share of the total costs.

And when it comes to filling portfolio gaps, MNCs can use a domestic player’s strong local brand to address a broader customer base – adding different price segments or adjacent product segments. U.S.-based medical device maker Medtronic has used M&A in large part to expand into new segments in China, beginning in 2008 when it set up a joint venture with Shandong Weigao Group, a major medical equipment company in China, to develop and market Medtronic’s vertebral and joint products. In 2012, Medtronic announced the acquisition of local Chinese orthopedics company Kanghui for more than $700 million.

As MNCs look for the best deals to help them gain these and other capabilities that can enable them to grow fast, they are finding out what works and what doesn’t. A well-devised system for joint ventures or acquisitions can be the single biggest contributor to a company’s growth in China and a key enabler of building a leading market position; a less-diligent approach can derail expansion. From our experience with clients in a range of industries in China, we have determined some approaches that boost the odds of inorganic growth success.

Why this deal?

In China as elsewhere, one of the keys to a deal’s success is to start out by knowing exactly what you hope to gain. Begin with a growth strategy that clarifies how M&A will enable growth, and then develop a prioritized target list – keeping in mind that in China deals may arise opportunistically. A ‘deal thesis’ spells out the reasons for a deal – generally no more than five or six key arguments for why a transaction makes compelling business sense. According to a Bain & Company survey of nearly 250 global executives, an acquirer’s management team had developed a clear investment thesis early on in 90% of successful deals. A deal thesis articulates on one page the business fit, strategic importance, acceptable valuation range, key risks, and potential integration issues.

Achieving profitable growth in China is increasingly difficult. When MNCs can’t reach their strategic goals organically, they turn to joint ventures and M&A.

In China, few companies have been as systematic in the use of a deal thesis as China Resources Snow Breweries (CRB), the SABMiller and China Resources Enterprise joint venture. Since joining forces in 1994 (SABMiller owns 49%, China Resources controls 51%), the joint venture has completed dozens of regional brewery acquisitions in China, integrating brands and operations. Drawing on more than 115 years of brewing experience and more than 200 brands across 75 countries, SABMiller brought its significant brewing expertise and low-cost experience to the table, as well as its ability to quickly integrate and consolidate new acquisitions to create scale. China Resources brought its local market knowledge and key relationships. When the joint venture looks for acquisitions, it evaluates whether – and how – SABMiller’s and China Resources’ strengths can be used to make the deal a success. SABMiller offers M&A capability, a systematic approach to managing post-merger integration complexity, and experts who maintain stringent quality control via lab tests and factory visits. China Resources contributes a local network that serves as a source for promising deals, and strong government relationships that ease approval processes.

Consider how the joint venture built Snow beer into a single national brand. Acquired brewers’ production capacity was converted to Snow beer, which is now produced across 22 provinces. Snow is the best-selling beer in ten provinces and cities. The joint venture enhances local brewing operations with new equipment, imports CRB’s best practice management systems, and centralizes functions to achieve benefits of scale. For example, 90% of procurement costs are centralized.

Using its proven M&A approach – which always starts with a deal thesis – China Resources Snow has outgrown the competition to become the clear market leader, with a 21% share of China’s beer market. It is now the world’s number one beer brand by volume.

How to get there

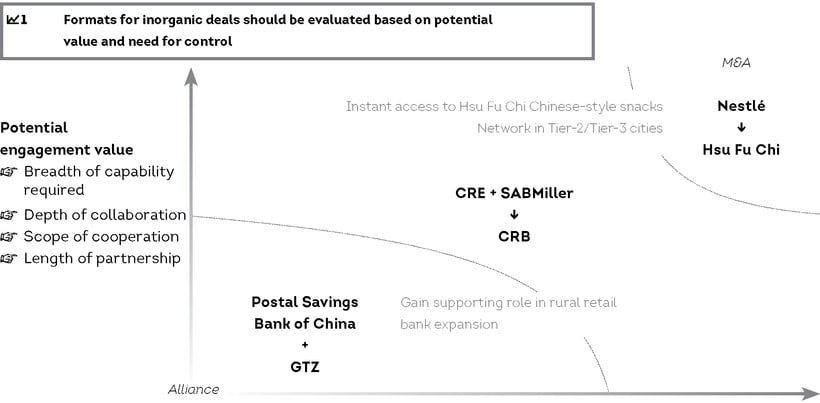

Once a company understands why it’s doing a deal, the next big decision involves whether to embark on a joint venture or acquire majority ownership through an M&A. Both have been successful paths to growth for companies in China.

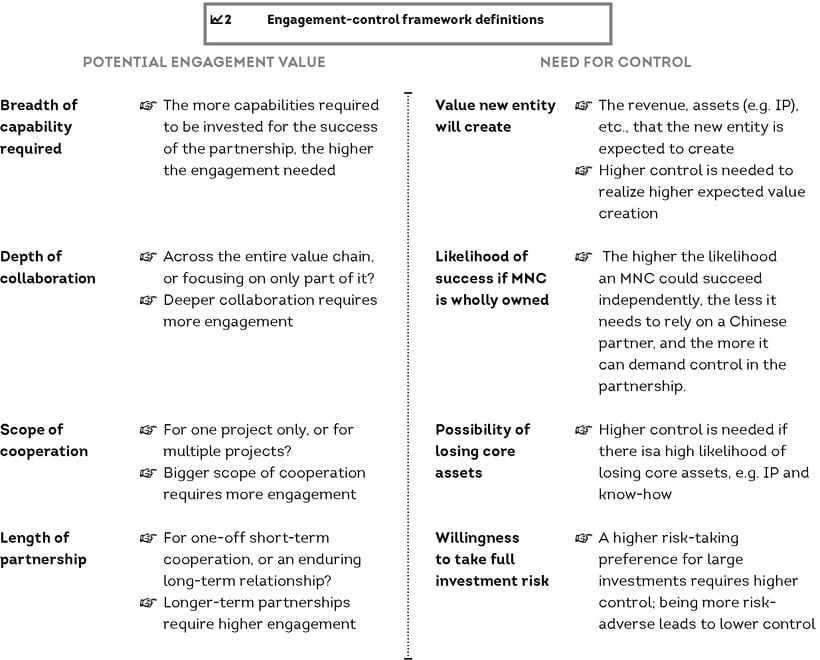

Bain & Company has developed a framework for helping companies decide which of the two options is most appropriate, based on two factors: the potential value the deal can bring, and the MNC’s need for control. Companies ask and answer a series of questions designed to help them clearly understand the potential engagement value and level of control required.

For example, determining the potential value means looking into the breadth of the capability required, depth of collaboration, scope of cooperation and length of the partnership. Assessing the need for control requires determining the value the new entity will create, the chances of success if the MNC advances on its own, the possibility of losing core assets such as IP – a serious consideration for foreign companies operating in China – and the willingness to take the full investment risk. The higher the value and need for control, the more likely M&A is the best option. Whenthe engagement value and need for control are relatively low, it is wise to consider JVs.

Whichever path a company takes, its odds of winning improve greatly by taking a rigorous, replicable approach to succeed and mitigate risks.

Venturing jointly

In dozens of sectors, ranging from healthcare to finance, government restrictions make JVs the only feasible option – and some have been highly profitable. But when many MNCs in unrestricted industries consider venturing with Chinese players, they often stop cold when they spell out the potential challenges. The list is long: misaligned agendas between the global and local players; poor governance or organizational control among the players; contract noncompliance; technology infringement; and the risk that the partner may become an eventual competitor in the same market. That is why the approach needs to be tailored to China’s unique opportunities and risks. Joint ventures require careful screening of potential candidates to address the tricky issues early as part of contract negotiations and joint business planning, and agreement on key business drivers and ongoing management and monitoring.

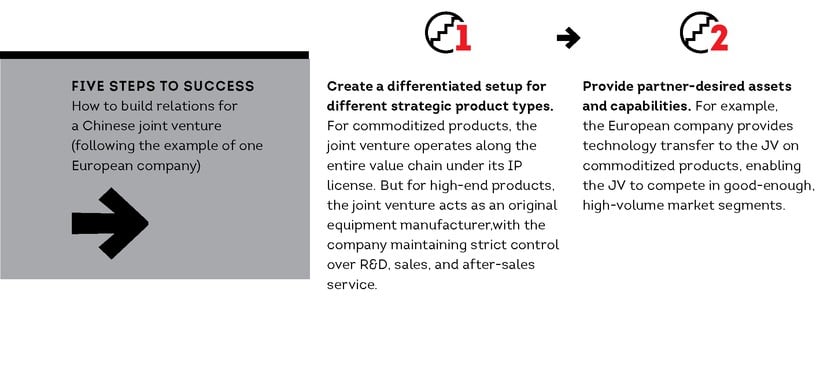

That was the approach taken by a European manufacturer of heavy industrial equipment. The company knew it had to win in China – it was essential to winning globally – but faced strong competition from Chinese players with good-enough products. It decided to set up a joint venture to improve its cost competitiveness and local reach. To protect itself against the loss of IP, it focused most of its efforts on products with low IP sensitivity. The company maintained its portfolio of high-end products, but used the joint venture to help it control costs to the point that it could achieve its desired margins.

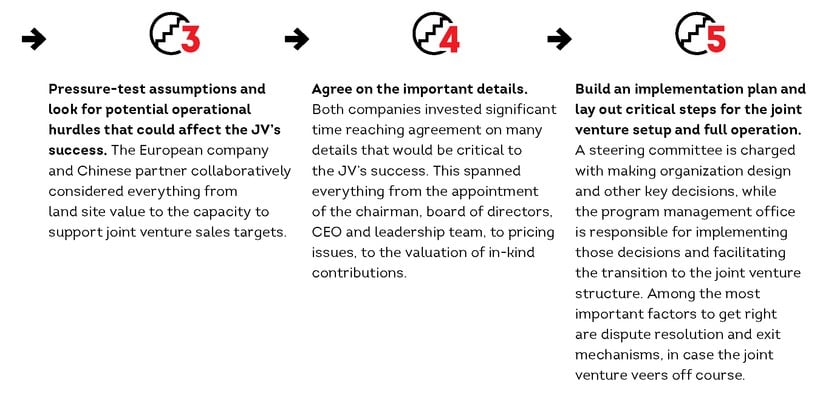

One of the reasons players have resisted joint ventures in the past has been the fear that such deals take a long time to close – and that results are slow to be achieved. In our experience, when done right, joint ventures deliver successful outcomes relatively quickly. The European heavy industrial equipment company set up its JV with a Chinese company less than a year after signing a letter of intent. Key to the success of any deal is to clearly understand what each party brings to the table, and to ensure the joint venture will accommodate the unique needs of each party. The European company used a five-step approach to build a solid foundation for the joint venture (see Five Steps to Success).

Turning to M&A

The challenges for companies pursuing M&A in China are well known. One of the biggest obstacles is that it is a market in which good target companies are hard to find. About 75% of deal activities are sourced from proprietary networks or brokers, and the success rate for closing deals is low – less than half the rate of closing in the United States. Due diligence poses thorny problems due to the lack of transparency and established accounting and financial reporting processes, and it is also a lengthy process. Valuations are high, and post-acquisition improvements are hard to achieve, as cultural differences create integration challenges and the top management drain hurts target value and employee morale. Meanwhile, approaches that work in other regions – to simply adopt the acquirer’s best practices and expertise, for example, – often don’t work in China.

Again, companies that succeed begin with a clear strategy and investment thesis. They also have an integration thesis and process that is designed to capture the key elements of the deal thesis while simultaneously managing the risks. They know what they are looking for and how it will fit with their strategy. They know how they plan to integrate it, if at all. They carry out systematic screening. Only then are they positioned to make a disciplined investment decision.

Consider the case of a multinational spirits company that saw M&A as its only chance to gain scale in China, where there was relatively little demand for its high-end and premium brands. The company thoroughly screened adjacent sectors to assess and prioritize opportunities, looking at companies in different price segments, psychographic segments and demographic segments, among others. With 1,400 companies in selected sectors, it first screened candidates by size, only evaluating the top 50 players in selected segments. The company then screened for regional market position and price segments (it looked at high-growth segments where they could potentially shift to premium offerings). Finally, it considered availability, narrowing its list further to include only companies with no equity investment from other strategic investors. After making field visits, it then short-listed companies based on business fit, willingness, and business attractiveness.

Finding the right acquisition candidate is one thing, but the process of planning and executing integrationcan make or break a deal. Companies need to designan explicit, pragmatic, integration blueprint, and targetsto unlock value.

In our experience, companies that get M&A right benefit from an institutional M&A capability: they build a dedicated core M&A team with the right transactional experience. They involve product line staff early on and make them accountable for long-term results. They set clear M&A policy and target assessment criteria, and they know when to walk away from a deal, determining the price at which a deal will be killed. Lastly, they use an incentive system to drive the right deals – not just any deal.

This approach is the reason Dutch chemicals and life sciences group Royal DSM is now on a winning path in China. The company relies on a team with deal and frontline experience. Separate teams are responsible for medium to large M&A deals like the 2005 acquisition of Roche (Shanghai) Vitamins; early-stage and expansion deals like the 2008 equity investment in Tianjin Green Bio-Science; and IP-based transactions such as licensing agreements.

Teams repeatedly execute M&A deals, carefully following an institutionalized process as they fulfill well-defined responsibilities. For example, in larger deals, the China business development team is responsible for identifying synergies and integration costs and risks, while the China strategy and acquisition team arranges deal structuring and finance.

Institutionalizing its M&A capability has allowed Royal DSM to make acquisitions the driving force behind its growth strategy in China. Before embarking on its acquisition strategy, China represented only 4% of the company’s total revenues. By 2010, China had grown to contribute 10% of its global total, according to data from Capital IQ. The company’s first big stepwas realizing it couldn’t capture Chinese potential on its own. Now that it has perfected the M&A process, the opportunities ahead for Royal DSM are as vast as China itself.