Taming the China Bears

The market is always in search of a story, and investors, it seems, think they have found a new one this year in China. The country’s growth slowdown and mounting financial risks have spurred a growing wave of pessimism, with economists worldwide warning of an impending crash.

But dire predictions for China have abounded for the last 30 years, and not one has materialized. Are today’s really so different?

The short answer is no. Like the predictions of the past, today’s warnings are based on historical precedents and universal indicators against which China, with its unique economic features, simply cannot be judged accurately.

The bottom line is that the complexity and distinctiveness of China’s economy mean that assessing its current state and performance requires a detail-oriented analysis that accounts for as many offsetting factors as possible. Predictions are largely pointless, given that the assumptions underpinning them will invariably change.

Consider China’s high leverage ratio, which many argue will be a key factor in causing a crisis. After all, they contend, developing countries that have experienced a large-scale credit boom have all ended up facing a credit crisis and a hard economic landing.

But several specific factors must be accounted for in assessing whether this is China’s fate. While China’s debt-to-GDP ratio is very high, the same is true in many successful East Asian economies such as Taiwan, Singapore, South Korea, Thailand, and Malaysia. And China’s saving rate is much higher. Ceteris paribus, the higher the saving rate, the less likely it is that a high debt-to-GDP ratio will trigger a financial crisis.

In fact, China’s high debt-to-GDP ratio is, to a large extent, a result of its simultaneously high saving and investment rates. And, while the inability to repay loans can contribute to a high debt burden, the nonperforming-loan (NPL) ratio for China’s major banks stands at less than 1%.

If, based on these considerations, one concludes that China’s debt-to-GDP ratio does constitute a substantial threat to its financial stability, there remains the question of whether a crisis is likely to occur. Only when all of the specific linkages between a high debt burden and the onset of a financial crisis have been identified can one draw even a tentative conclusion about that.

China’s real-estate price bubble is often named as a likely catalyst for a crisis. But how such a downturn would unfold is far from certain. Let us assume that the real-estate bubble has burst. In China, there are no subprime mortgages, and the down payment on the purchase price required to qualify for financing can exceed 50%. Given that property prices are unlikely to fall by such a large margin, the bubble’s collapse would not bring down China’s banks. Even if real-estate prices fell by more than 50%, commercial banks could survive – not least because mortgages account for only about 20% of banks’ total assets

China’s real-estate price bubble is often named as a likely catalyst for a crisis. But how such a downturn would unfold is far from certain.

Let us assume that the real-estate bubble has burst. In China, there are no subprime mortgages, and the down payment on the purchase price required to qualify for financing can exceed 50%. Given that property prices are unlikely to fall by such a large margin, the bubble’s collapse would not bring down China’s banks. Even if real-estate prices fell by more than 50%, commercial banks could survive – not least because mortgages account for only about 20% of banks’ total assets.

At the same time, plummeting prices would attract new homebuyers in major cities, causing the market to stabilize. And China’s recently announced urbanization strategy should ensure that cities’ demographic structure supports intrinsic demand. If that were not enough to ward off disaster, the government could purchase unsold properties and use them for social housing.

Moreover, if necessary, banks could recover funds by selling collateral. As a last resort, the government could step in, as it did in the late 1990s and early 2000s, to remove NPLs from banks’ balance sheets. Indeed, China has a massive war chest of foreign-exchange reserves that it would not hesitate to use to inject capital into commercial banks.

That remains a highly unlikely scenario. China’s banking system does face risks stemming from a maturity mismatch between loans and deposits. But the mismatch is less severe than some observers believe. In fact, the average term of deposits in China’s banks is about nine months, while medium- and long-term loans account for just over half of total outstanding credit.

A more salient threat would arise if the government pursued too much capital-account liberalization too fast. If China eases restrictions on cross-border capital flows, an unexpected shock could trigger large-scale capital flight, bringing down the entire financial system. Given this, it is vital that China maintains controls over short-term cross-border capital flows in the foreseeable future.

Likewise, the Chinese government must address a fundamental contradiction. Monetary interest rates have increased steadily, owing to rampant regulatory arbitrage (whereby banks find loopholes that enable them to avoid unfavorable rules) and the fragmentation of the credit market, while return on capital has fallen rapidly because of overcapacity.

If the Chinese government fails to reverse this trend, a financial crisis – in one form or another – will become inevitable. But, given the authorities’ broad scope for policy intervention, the crash will not come anytime soon – if it comes at all.

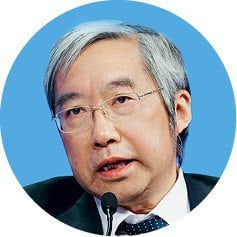

Yu Yongding is former President of the China Society of World Economics and Director of the Institute of World Economics and Politics at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences. He has also served as a member of the Monetary Policy Committee of the People’s Bank of China, and as a member of the Advisory Committee of National Planning of the Commission of National Development and Reform of the PRC.