The War of Canals

Vladimir Volkov

Panama and Nicaragua will be able to take over the most vital transit corridor in the global trade between the West and the East as early as the end of the next decade. Whether this will become reality depends on the success of the ambitious construction projects and the modernization of maritime transport canals promoted by the local authorities. Competition between them will also decide the distribution of profits derived from the transit of goods through these routes, the level of which is likely to reach $1.4 trillion by 2030.

Wednesday, 23 April, turned out to be a red-letter day for 70,000 construction workers in Panama, but not because it was a holiday – the reason lay elsewhere. It was on this date that national trade union Suntracs led its members on an indefinite strike demanding that the government improve working conditions and increase wages by 20%. Saul Mendez, Secretary General of Suntracs, stated at the time that such a raise would be fair as it was in keeping with revenue growth in the construction industry.

Suntracs’ action affected many construction sites, chief among them the country’s most ambitious infrastructure construction project – the reconstruction of the Panama Canal. The monotonous howling of dozens of cranes tirelessly hoisting tons of iron, sand, and concrete, and feeding the insatiable appetite of a gigantic pit that stretched for dozens of miles; the revving turbo engines of quarry trucks and the clunking tracks of powerful bulldozers tossing scoopfuls of heavy coastal soil; the humming and buzzing of a motly army of construction workers with their bright yellow vests and helmets – all of these sights and sounds suddenly ground to a halt and were reduced to dead silence.

“The Panama Canal expansion project is completely paralyzed,” Mendez stated that day. The ‘April paralysis,’ which afflicted the project that had been initially envisaged to significantly strengthen Panama’s hand in the battle over global maritime trade flows, was hardly the first of its kind. Back in February, the operations had been interrupted for as long as two weeks following the Panama Canal Authority’s (ACP) refusal to meet the demands of its main contractor – Grupo Unidos por el Canal (GUPC), an international consortium comprising Spain’s Sacyr Vallehermoso, Italy’s Impregilo, Belgium’s Jan De Nul, and Panama’s own Constructora Urbana – to increase the project appropriations by $1.6 billion on top of the original contracted budget of $3.1 billion.

At that time, GUPC said that their claims were motivated by the inevitable new expenditures resulting from errors in technical documentation and construction cost estimates that had been deliberately undervalued by the Canal Authority. In response, ACP accused GUPC of attempting to blackmail the authorities. “From the very outset I’d like to make it perfectly clear that blackmail will not affect our stance. Our company – the canal operator – intends to meet all of the project deadlines. It needs to be fully completed by 2015, with or without the Spanish consortium,” stated Jorge Quijano, Panama Canal Administrator.

They managed to partially resume the operations only on 21 February following a round of difficult and emotionally charged negotiations between ACP and GUPC that resulted in a compromise: an agreement was reached to invest an additional $100 million into the reconstruction project and refer the outstanding dispute to an international court of arbitration.

The Canal Administration’s frustration and exasperation underlying its implacable position cannot be explained just by their reluctance to pay a single cent on top of what is otherwise an exceedingly costly project with a price tag of $5.25 billion. Officials are clearly concerned that the canal reconstruction project, which started in the summer of 2009 and is already exactly one year behind the original schedule, might be delayed even further. In the meantime, every minute counts – any delay is not only likely to cause the government of Panama additional costs and loss of profits, but the authorities also run the risk of forfeiting their potential market share that is already coveted by the competition.

Time for Post-Panamax

Time for Post-Panamax

In fiscal year 2013 (that ended on 30 September), the cargo traffic routed through the Panama Canal fell 4.1% down to 320 million tons. “The downturn mostly has to do with the loss of US grain cargo to Argentina, which uses an alternate route,” explained Jorge Quijano in an interview to Seatrade Global. The amount of commission charged for the same period remained at the previous year’s level and totaled $1.85 billion. However, a drop in revenues could only be avoided thanks to a new commission structure approved by the Panamanian authorities in the summer of 2012, which saw an increase in fees from 1% to 7% for the transportation of selected categories of cargoes.

Time and again it has proven something that remains an open secret – the capacity of the hundred-year-old Panama Canal has reached its limit. Given its present shape, the 81-kilometer long transportation system connecting the Pacific and the Atlantic oceans is capable of accommodating up to 35 ships per day on average. The actual demand is much greater, meaning that the wait time can take weeks. The story of the Erikoussa tanker that had to pay a record sum of $220,400 for the right to sail through the canal ahead of a queue of 90 ships has long become a textbook example. Had the ship owners in question chosen to follow the standard procedure, they would have only had to part with $13,400.

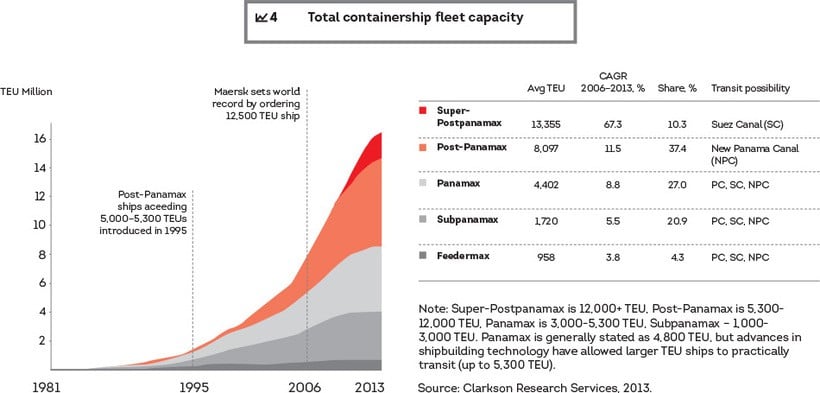

In addition, the limitations resulting from the size of lock gates and the depth of the waterway restrict the Panama Canal’s capacity to Panamax class ships (965 by 106 feet), which are rather average in size given today’s standards. Based on the aforementioned considerations, ship owners have in recent years increasingly favored alternative routes, including the Suez Canal and the Strait of Malacca, even in the face of greater distances and the risk of piracy.

The expansion of the Canal was designed specifically to address both these problems, and should double its throughput capacity while increasing revenues two- to four-fold. According to the approved plans, two new three-chamber, 1,400-foot locks are to be built, one on each side of the Canal. They will connect both new and existing navigation channels, which will be expanded and deepened. All of these measures combined will enable the Canal to accommodate a more modern class of ships, Post-Panamax, including several types of super tankers and container ships that are likely to account for the lion’s share of the increase in maritime traffic in the foreseeable future.

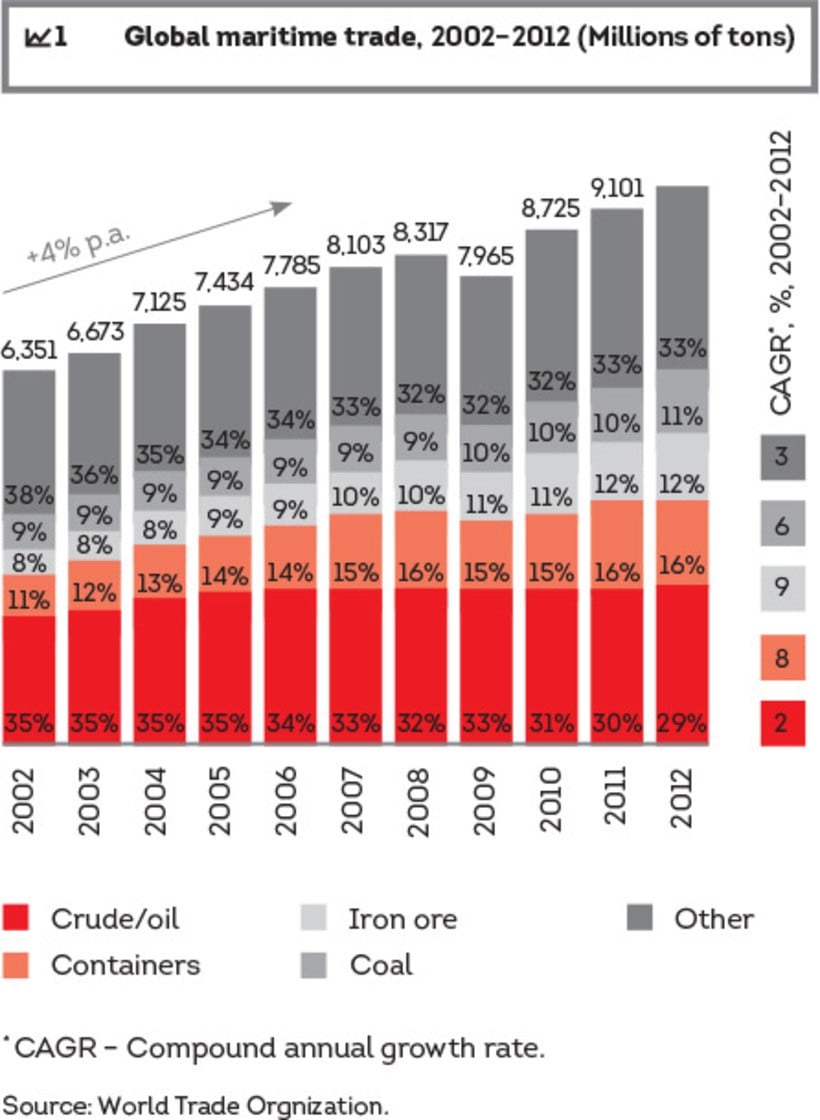

All of the logic underlying the development of global trade in recent years seems to point to that conclusion. During the global economic boom between 2000 and 2008, it grew by 12% annually on average. The recent crisis slowed this dynamic, and by the end of 2013, the global commodity turnover reached a record $19.9 trillion. The share of maritime traffic that had historically fluctuated between 75% and 90% exceeded 9 billion tons.

The structure of maritime trade was also changing. Due to the high growth rate of cargo traffic between the largest Asian markets and their partners in the Americas and Europe, the share of long-distance routes has been steadily on the rise in recent years. In particular, they accounted for as much as 27% of all maritime container traffic in 2011. Major operators’ desire to service these routes with maximum efficiency led to more demand for larger ships. Since 1996, the tonnage of international container flagships has tripled from 6,000 TEU (the twenty-foot equivalent unit, an inexact unit of cargo capacity often used to describe the capacity of a standard 20-foot-long container) to 18,000 TEU for the newest Maersk Triple E class ships.

In the foreseeable future, these trends are likely to persist. According to current forecasts, maritime traffic will continue to grow between 3% and 4% annually until the end of the current decade. As the “Chinese miracle” continues and the US economy remains on the path to recovery, long-haul routes are likely to account for the bulk of the increase in cargo traffic. By extension, the tonnage of cargo ships is expected to increase as well, as confirmed by growing investments into corresponding port infrastructure.

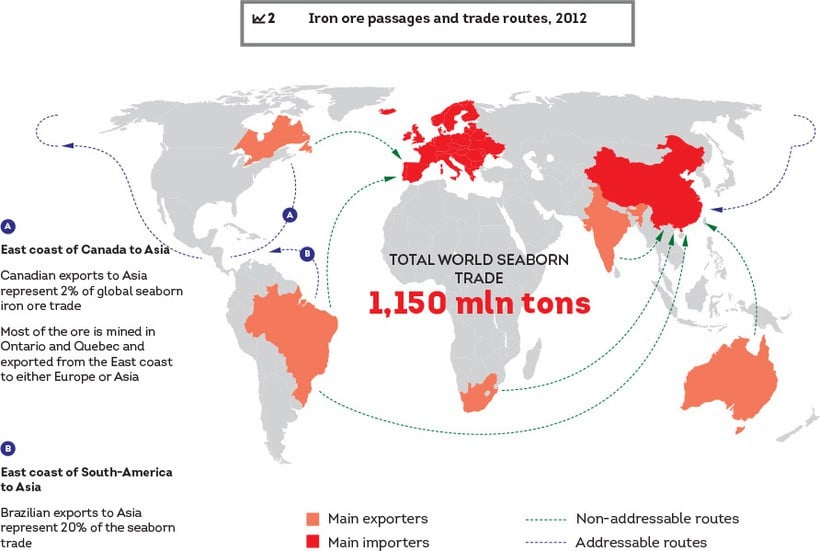

The HKND Group estimates that fuel savings made possible by using ships with larger tonnage to service long-haul routes through the Nicaragua channel are going to be quite significant. For instance, the distance between Shanghai and Baltimore through NIGC would be approximately 4,000 kilometers shorter than through the Suez Canal and 7,500 kilometers shorter compared to sailing around the Cape of Good Hope. Given the current price of fuel for medium size container ships, the total savings are estimated at $500,000 and $1 million, respectively. If ships with larger tonnage are used, the costs per TEU will be $110 and $327 lower for the first and the second alternative routes, respectively, mainly thanks to fuel savings

The Panama Canal expansion project was designed with these prospects in mind. If the operations do not stumble into another schedule overrun, the Canal will be able to accommodate Post-Panamax container ships with the capacity of up to 13,000 TEU. However, even these giants will soon have to fight for a place under the sun in the face of tough competition from veritable dreadnoughts – the Super-Post Panamax class ships. Today, these already account for one-tenth of the tonnage carried by the global container fleet, and forecasts show that this figure is only likely to grow in the future. However, the size of these ships is so large that they will not be able to navigate through the Panama Canal even after the reconstruction project is completed.

At Any Cost

At Any Cost

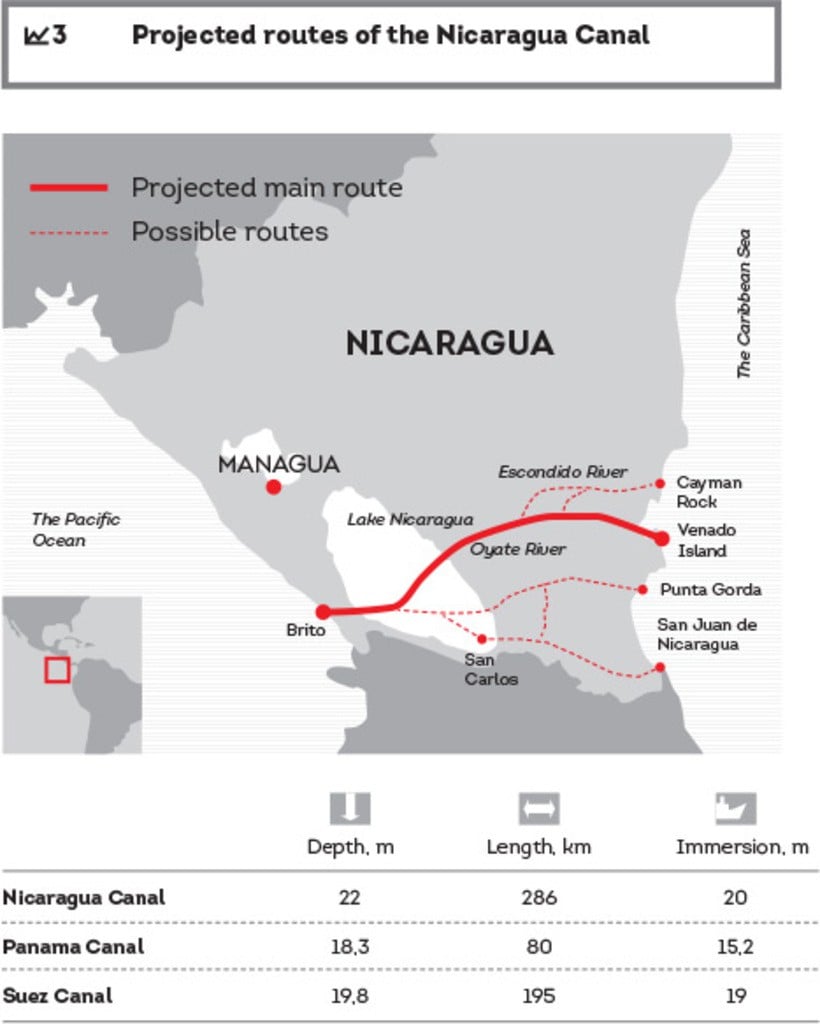

This particular circumstance along with the stellar prospects demonstrated by the global market were undoubtedly taken on board in Managua when the decision was made to launch a project to build the Nicaragua Interoceanic Grand Canal (NIGC) that could seriously weaken the hand of its Panamanian competitor in the battle for transit flows in the region. The project was formally started in summer of 2012 when the Nicaraguan parliament adopted a special law to determine the legal status of the future canal and the ways to administer it. In the fall of the same year, the exclusive right to develop and manage NIGC based on a 50-year concession was awarded to China’s HK Nicaragua Canal Development Investment.

According to the blueprint, the new transport system will be more than three times the size of the Panama Canal (265 kilometers long, 250 meters wide, and 22 meters deep) both in terms of its length and capacity. The new canal will even be able to accommodate Super-Post Panamax class ships, which would certainly redefine all transit routes in the region.

“The project has great potential and is capable of changing the global trade landscape and yielding great economic and social dividends for Nicaragua, its neighbors, and all of Latin America. It is designed for the transit of raw materials such as oil, liquefied natural gas, and steel from the United States to Asia, or iron ore from Brazil,” explained Ronald MacLean-Abaroa, representative of the HKND group, during a press conference last year. “Today, there is a great need for a new state-of-the-art canal capable of complementing the Panama Canal capacity and accommodating large ships.”

The ambitious construction project, with an estimated price tag of $40 billion, is scheduled for completion within the tightest possible deadlines. The first ship could pass through NIGC in December 2019, just five years after construction began. In another ten years, the project will be completed in full.

Such a pace may seem unrealistic considering the scope of challenges faced by the concession holders. Many skeptics point to some unprecedented technical difficulties and enormous costs of the project that also envisages the creation of two free trade zones, construction of two deep water ports, a railway, an international airport, and an oil pipeline, doubting that HKND would be able to raise the required financing and attract the requisite expertise.

A separate issue that the NIGC organizers had to face was a legal collision between the laws governing the project and the country’s constitution. In particular, what seems to be at stake here is a de facto expropriation of community-owned lands and property along the canal site, as well as assigning HKND concession rights to use large chunks of the adjacent territory on a long-term basis and free of charge. Critics of the project are concerned that this might compromise the local communities and even deprive the country of a part of its sovereignty. “It’s like there’s an unwritten slogan: ‘The canal at any cost,’” notes Manuel Ortega Hegg, Vice President of Nicaragua’s Academy of Sciences. More than thirty complaints have already been lodged in this respect with the Supreme Court of Nicaragua.

Ultimately, it is the environmentalists who speak the loudest against the construction of the Nicaragua Canal. Their greatest concerns have to do with the fate of the Nicaragua Lake, slated to accommodate around 80 kilometers of NIGC. There is a risk that the construction may destroy the ecosystem of this unique body of water, which is a potential drinking water source and national security priority site.

Is there enough room for everyone?

Up until now, HKND has responded to these concerns by saying that it is confident of its own capabilities. The company has already retained the services of the leading international consulting and engineering companies to work on the project, including McKinsey & Company and China Railway Construction Corporation – they have been called upon to help build the most efficient financial and engineering model to make the project easier to understand and more attractive to the community of investors. Nobody at HKND seems to doubt that there will be plenty of willing investors in the project. “Our negotiations with international investors have been moving along rather smoothly all this time. We have already reached agreements with some of them,” said HKND CEO Wang Jing in an interview published last October in South China Morning Post.

The Nicaraguan authorities have a tremendous vested interest in seeing the project through to its successful completion, and should therefore help to alleviate legal risks and sort out environmental issues. By as early as 2015, the government expects to receive canal revenue that could boost GDP growth by as much as 15%, and even double it by 2018. For the country ranked among the poorest in Central America, this is quite significant.

The commission that the Nicaraguan state budget is expected to cash in will also grow over time. According to the agreement with the HKND Group, the company will pay around $10 million each year into the country’s budget. Furthermore, ten years into the Canal operations, Nicaragua stands to receive a 10% stake in the Canal management company and is slated to become a full proprietor in 100 years.

At this stage, the Nicaraguan authorities prefer to talk not as much about the competition between these two projects as about a healthy synergy, claiming that there would be enough room in the prospective market to go around for everyone. The HKND Group estimates that by 2030, the aggregate trade routed through the Panama and Nicaragua Canals will grow 240%, while the aggregate cost of transit cargoes is expected to exceed $1.4 trillion per year, which is likely to make this corridor one of the most pivotal trade routes in the world. All of it means that the invisible war waged over the distribution of these revenues is going to get even fiercer and its outcome is being decided right now.